OCTOBER 2025

TL;DR is a monthly digest summarizing the vital bits from the previous month's How to Live newsletter so you don't miss a thing.

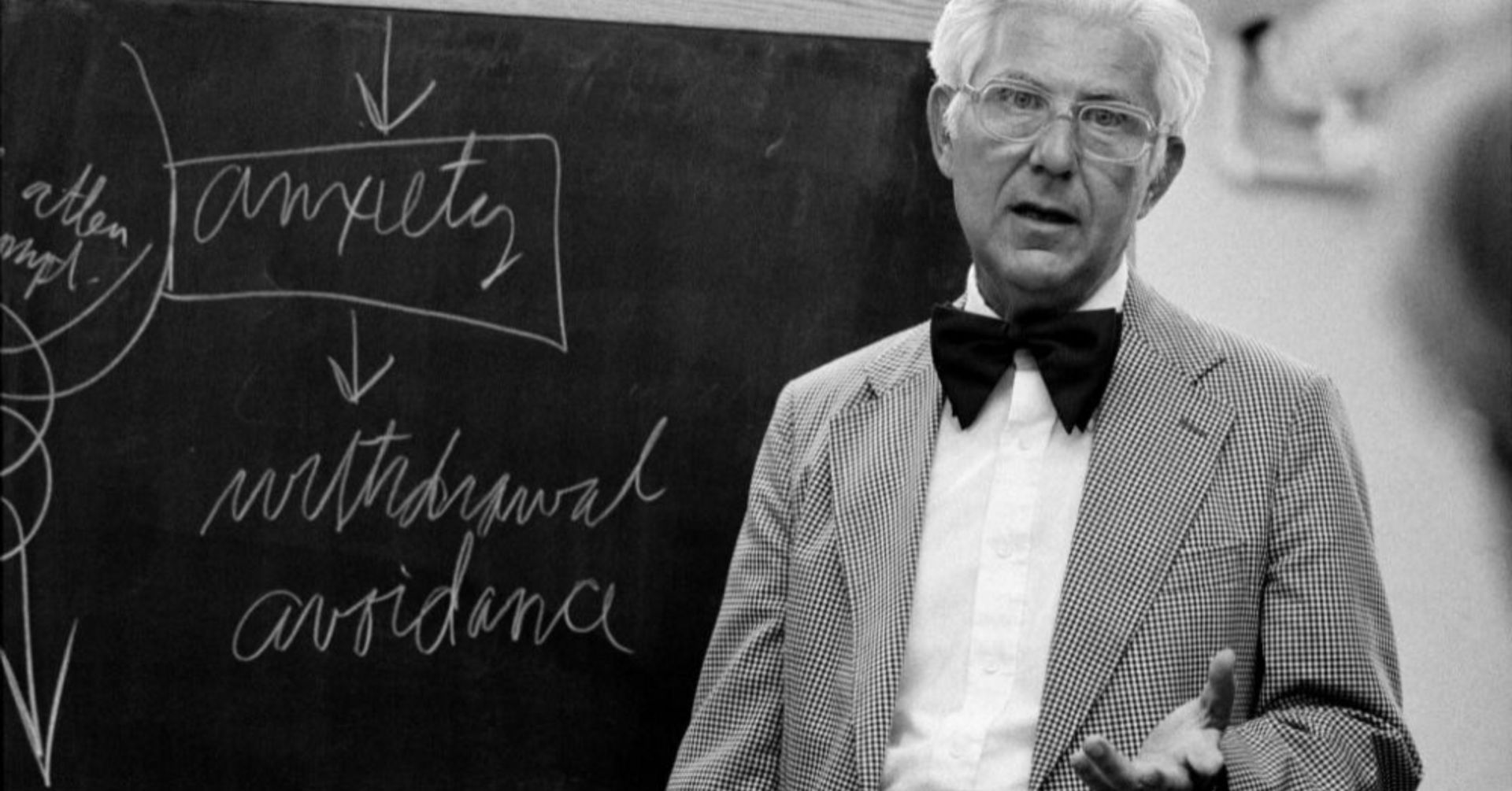

On October 1st 2025, I Wrote About How Our Brains Lie to Us and the Psychiatrist Who Proved it.

Nobody likes me. I’m a failure. I’m too ugly to love.

Our thoughts are so convincing that we often mistake them for truth.

We confuse feelings for facts, invent fictions on behalf of others, and cling to our own distorted interpretations of events. And when we act on our misguided thoughts, we typically wind up on the wrong side of truth — because the mind lies.

It’s absurd!

And until 50 years ago, psychology had no systematic way to help people stop it.

In the 1960s, the psychiatrist Aaron Beck was watching his depressed patients play a simple card-matching game. According to everything he'd learned in medical school, success should have made them feel worse. Freudian theory insisted that depressed people had an unconscious "need to suffer"—so achievement would threaten their psychological equilibrium and deepen their misery.

Instead, Beck's patients grew more confident, and their moods improved with each correct match.

This shouldn't have happened. It violated the fundamental principles of psychoanalysis that had dominated psychiatry for decades. But Beck couldn't ignore what he was seeing: his patients' moods weren't being controlled by mysterious unconscious drives. They were being hijacked by the thoughts they were having right now, in real time.

Beck had stumbled onto something that would revolutionize how we understand human misery: Depression isn't a disease. It's a con game your mind is running on you.

Beck discovered that your brain operates like a particularly skilled con artist. It presents distorted thoughts with such confidence that you never think to fact-check them.

I failed that presentation becomes I fail at everything. She didn't text me back becomes Nobody likes me. I made a mistake becomes I'm worthless.

What feels like insight is a cognitive hijacking. Your brain takes isolated incidents and spins them into convincing narratives about your fundamental inadequacy as a human being.

Here’s what makes the scam so effective—once you believe these thoughts, you start acting in ways that make them come true. You stop trying, avoid challenges, isolate yourself—and then point to these behaviors as proof that your thoughts were right all along.

It's a closed loop of self-destruction that most people never realize they're trapped in it.

On October 8th, I Wrote About The Discovery of a Victorian Confession Album Filled out by a 14 Year Old Marcel Proust.

When the French author (Valentin Louis Georges Eugène) Marcel Proust was fourteen, his friend Antoinette Faure asked him to fill out the questionnaire in her Confession Album.

These albums—Victorian keepsakes passed among friends—were the social media of their day: small bound books filled with questions like What is your idea of happiness? or What virtue do you most admire? While they aimed to reveal a person’s essence, what they really captured was their curated self, the version meant to be admired.

That is: the self that answers a questionnaire is not the self that creates, dreams, or loves. It’s a performed version of identity.

Not unlike Instagram.

Still, even at fourteen, Proust refused to perform his identity. Where others flirted, exaggerated or bragged inside these albums, he confessed. His answers were unusually introspective, tender, and poignant.

You can already see the writer he would become, especially in his admission he most fears being separated from his mother (🥲).

Proust at 15

In 1924, two years after Proust’s death, Antoinette Faure’s son, André Berge, discovered her Confession Album in a pile of her things. When he shared Proust’s teenage answers in the magazine Les Cahiers du Mois (a short-lived but culturally significant French literary magazine published in the 1920s), they spread like an early form of virality—making the Proust Questionnaire a cultural artifact that would outlive them both.

Vanity Fair magazine adopted it, imitators followed, and soon everyone wanted to be privately profound in public.

To see the questions, and how Proust answered them, click the link below…

On October 15, 2025 I Wrote About Why Our Doubts Say More About the World Than About Us.

A few years back, a friend of mine won a major award and texted me from backstage, after winning: "What if they don’t let me keep it?”

I've heard versions of this from novelists, scientists, artists, scholars. The brightest people I know are often the ones most convinced of their own inadequacy. The most original thinkers fear their ingenious ideas are obvious.

Self-doubt tells us we're not good enough, that we'll never be good enough, and that everyone else knows how to do all the things we fear we're unable to do.

Everyone suffers from some degree of self-doubt. Trace it back, and you'll likely find yourself standing in childhood. For others, self-doubt doesn't arrive until adulthood crashes into them with a new challenge. Like many traits, self-doubt exists in both healthy and unhealthy forms. But if yours fuels your procrastination and indecision, you're struggling with an over-inflated sense of self-doubt.

For much of my life, I've been convinced there is a right way to be human, and I'm doing it wrong.

As a child, I spent nearly a decade taking IQ tests, which reinforced the faulty premise that information equaled intelligence. Retaining facts and figures meant you were smart. My brain was not wallpapered in graph paper, unable to easily synthesize data or catalog information. My brain was made from soft earth—I learn through doing, experiencing, feeling. The American education system insists there is one right way to learn: sitting all day and listening. This is counterintuitive to how I actually learn, but the system doesn’t care. I’m not a one-size-fits-all person, yet the system was built for only one size only.

Here's what they don't teach you in school: The agenda behind America's whole-cloth educational system is eugenic. It aimed to sift and sort, to classify and order human worth. Its ultimate goal was to establish a superior white race. The standardization of tests—including the SATs—was created by highly privileged white men who wanted to maintain white supremacy at all costs.

What does eugenics have to do with self-doubt?

Everything.

These systems created the world inside which we learned to operate. They gave rise to the fallacy that there is one right way to be a person, that superiority and inferiority exist as fixed categories, that society is built on this binary. And this binary feeds our self-doubt like gossip fattens a crowd.

It begs us to compare ourselves to others, to wonder whether we are better or worse. We're rewarded when we win and filled with shame when we don't. These indicators of success and failure masquerade as objective truth when they're actually arbitrary measures, best left for each individual to decide for themselves.

Then come the imaginary timelines. The milestones we're supposed to hit at precisely the right moment. Fail to reach one "in time" or bypass it altogether, and you'll discover your self-doubt reinforced everywhere you look.

Many of us don't reach these milestones. More people are choosing to become single parents, opting out of marriage, forgoing children. Yet the sense that we're "outsiders" remains. We feel like we're getting life wrong, filled with doubt about our ability to be human.

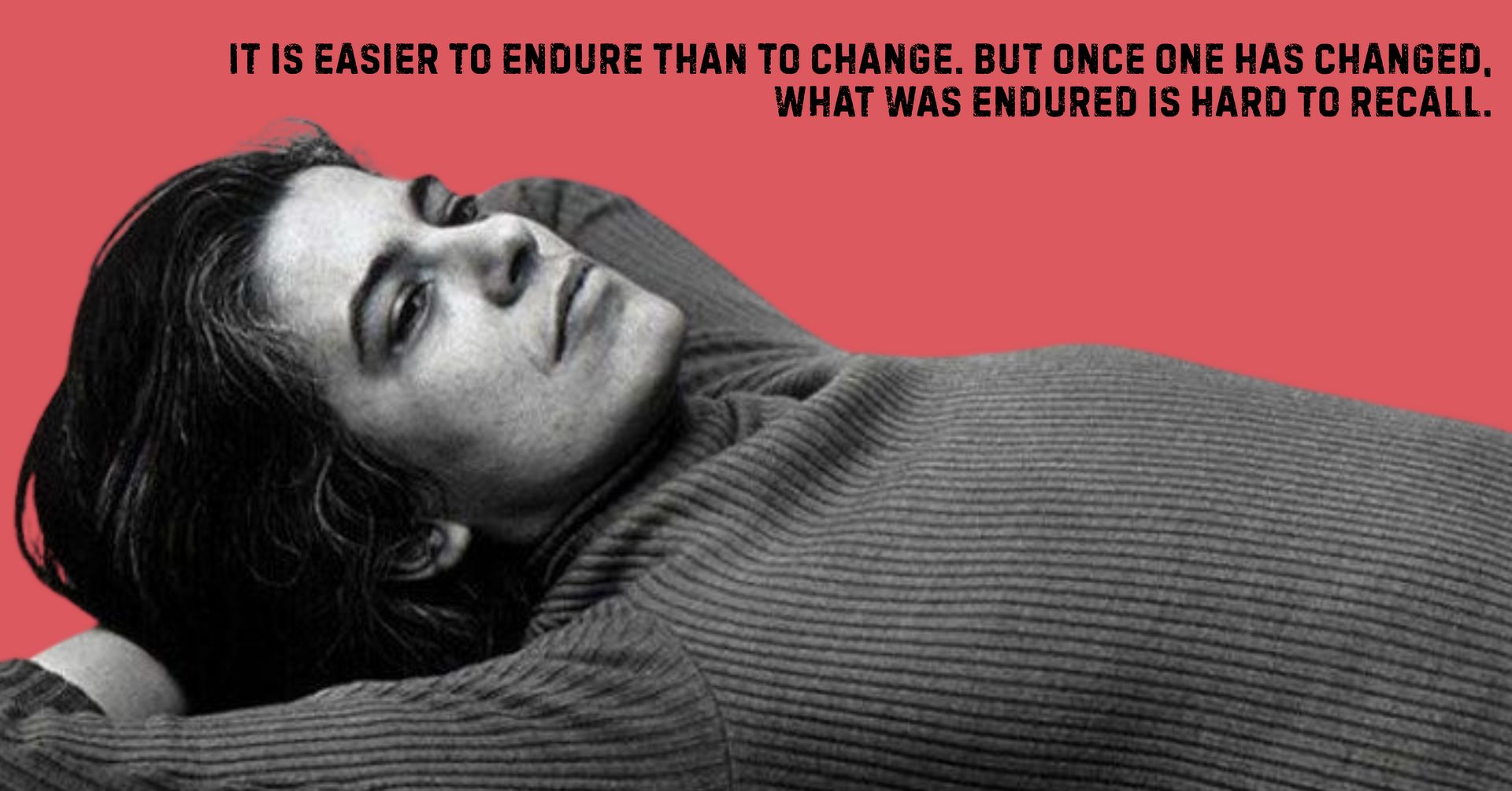

On October 22nd, 2025 I Wrote About How I Stopped Being Myself Long Enough to Get Better.

At the end of August, after a month spent upstate working exclusively on my next novel, I hopped in a car (to DRIVE IT) when a bout of depression came flying through the windshield, drenching me in its claggy funk.

By the time I could shake it off, it was too late—it had already wept through my skin and was walking on its hands in the deep end of my brain.

I spent the next few days crying, and when it was time to return home, I felt better—more stable. So, imagine my irritation when it found me again, a few days later, this time in Brooklyn. Ever clever, its form had changed, and now it wrapped itself around me like a weighted blanket, holding me hostage to an obnoxious anthem of outdated club-kid beats.

Good morning, my loser! Congratulations on having no family! You wanted kids, but you didn't have them. Probably for the best, because look at you—can't even get out of bed. No one remembers about you, and guess who hates you? Here’s a hint: Everyone!!

Every morning, I woke up into the same world, a groundhog’s day of rumination and awfulizing. The invisible filaments of energy that vibrate the universe into being scraped against my skin on the way to the kitchen, the dog park, and back to bed.

The world that was replaced itself by the world that wasn’t. My present life circumstances were amplified only by what wasn’t present. Instead, I lived inside the absence of the life I wanted but didn’t get. And I woke up every day as that person, in that life, with those same thoughts that don’t fade, but self-replicate.

Depression delivers each day as the same day over and over again. And every you as the same you whose same thoughts are driving you the same mad. Every sound, every sight, every thought and idea is the same, only louder, closer, like you’re a re-run in syndication, only poor, without residuals.

I needed out of my mind. I needed a new mind. Short of surgical intervention, the closest I could come was to pump in a new voice. I listened to one podcast after another on Buddhism, on Philosophy, and Meditation. Then on one of these podcasts someone said, “You need to break the habit of being yourself.”

Yes, I thought. That is what I need.

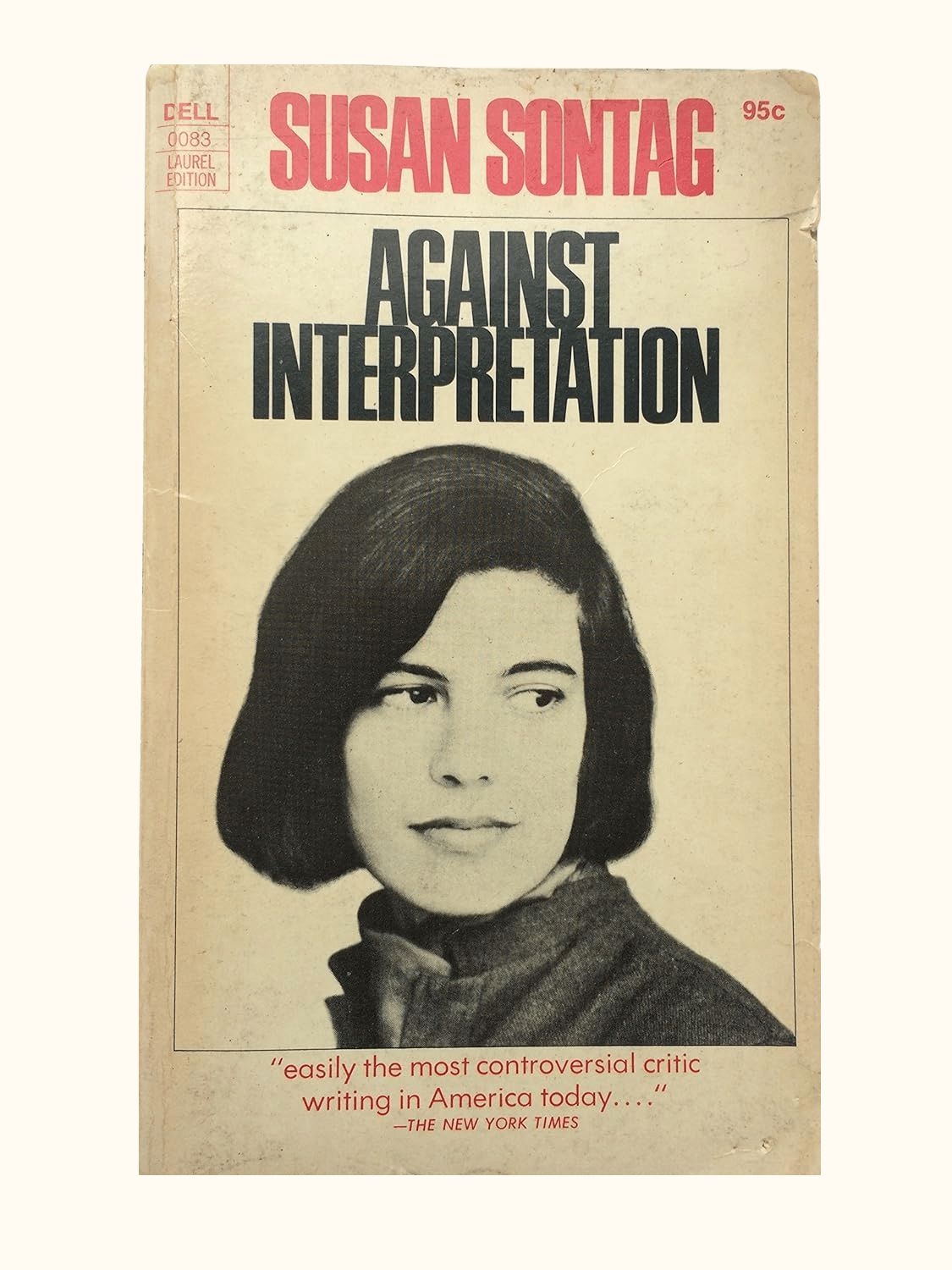

On October 29th, 2025 I Wrote About Why Direct Experience Transcends Knowledge.

The project of my life has been overcoming all that holds me back, and all that holds me back is my mind.

So, the project of my life is overcoming my mind.

Why is the mind so often the place where we get trapped? Why are we consumed with categories and labels, instead of living in accordance with the fluid who-ness of ourselves?

One reason, I assume, is to avoid feeling the discomfort in not knowing anything for certain. And uncertainty, as we know, is uncomfortable. To escape it, we travel to an even crueler climate—our mind, where we interrogate every interaction to convince ourselves that our fears are valid.

We spend so much time dissecting our social, romantic, and workplace interactions—analyzing personal dynamics, professional failures, and disappointments—yet so little time directly engaging with the sensory and emotional experience of life itself. The result? We wind up repeating much of what we'd hoped to avoid. After all, it is far easier to intellectualize emotion than to feel it—but where does this lead?

In the seminal essay from her 1966 book Against Interpretation, writer, intellectual and cultural critic, Susan Sontag protests against the habit of critiquing and analyzing art in favor of developing a more emotional connection with art and literature.

What she shares shifted how I think about thinking, and flipped my sense of self on its head. Maybe, just maybe, this book helped me see, I’m not actually wrong at my core, after all?

My hope is that this piece might do the same for you…

Read on…we’re about to get into it…

Thank you for subscribing! If you like this newsletter, please share it with friends!

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade