The Invention of Self-Doubt

There are things in your childhood where you have to say what your name is and pretend you’re a person, but I’m still not really a person, and I never really had to be a person in that way, because I feel like this other way of understanding the world makes more sense to me.

A few years back, a friend of mine won a major award and texted me from backstage, after winning: "What if they don’t let me keep it?”

I've heard versions of this from novelists, scientists, artists, scholars. The brightest people I know are often the ones most convinced of their own inadequacy. The most original thinkers fear their ingenious ideas are obvious.

Self-doubt tells us we're not good enough, that we'll never be good enough, and that everyone else knows how to do all the things we fear we're unable to do.

Everyone suffers from some degree of self-doubt. Trace it back, and you'll likely find yourself standing in childhood. For others, self-doubt doesn't arrive until adulthood crashes into them with a new challenge. Like many traits, self-doubt exists in both healthy and unhealthy forms. But if yours fuels your procrastination and indecision, you're struggling with an over-inflated sense of self-doubt.

For much of my life, I've been convinced there is a right way to be human, and I'm doing it wrong.

As a child, I spent nearly a decade taking IQ tests, which reinforced the faulty premise that information equaled intelligence. Retaining facts and figures meant you were smart. My brain was not wallpapered in graph paper, unable to easily synthesize data or catalog information. My brain was made from soft earth—I learn through doing, experiencing, feeling. The American education system insists there is one right way to learn: sitting all day and listening. This is counterintuitive to how I actually learn, but the system doesn’t care. I’m not a one-size-fits-all person, yet the system was built for only one size only.

Here's what they don't teach you in school: The agenda behind America's whole-cloth educational system is eugenic. It aimed to sift and sort, to classify and order human worth. Its ultimate goal was to establish a superior white race. The standardization of tests—including the SATs—was created by highly privileged white men who wanted to maintain white supremacy at all costs.

What does eugenics have to do with self-doubt?

Everything.

These systems created the world inside which we learned to operate. They gave rise to the fallacy that there is one right way to be a person, that superiority and inferiority exist as fixed categories, that society is built on this binary. And this binary feeds our self-doubt like gossip fattens a crowd.

It begs us to compare ourselves to others, to wonder whether we are better or worse. We're rewarded when we win and filled with shame when we don't. These indicators of success and failure masquerade as objective truth when they're actually arbitrary measures, best left for each individual to decide for themselves.

Then come the imaginary timelines. The milestones we're supposed to hit at precisely the right moment. Fail to reach one "in time" or bypass it altogether, and you'll discover your self-doubt reinforced everywhere you look.

Many of us don't reach these milestones. More people are choosing to become single parents, opting out of marriage, forgoing children. Yet the sense that we're "outsiders" remains. We feel like we're getting life wrong, filled with doubt about our ability to be human.

Without comparison, self-doubt could not exist. So long as we compare ourselves to and against others, we will always find ways to feel better or worse about ourselves. There is no category where individuality and difference is the norm. That would allow too much room for everyone, and the system can't function that way.

Do you have trouble taking compliments?

If you answered yes to more than one, you're probably grappling with self-doubt.

And here's a cruel irony: When people who fall outside the "norm" finally achieve something—when you're placed in the public eye, promoted, win a prize—the self-doubt doesn't disappear. It escalates. Success doesn't cure self-doubt. It amplifies it.

When we respond to self-doubt in maladaptive ways, we freeze our false beliefs about ourselves in place instead of allowing them to grow and change. Self-doubt gives rise to procrastination, perfectionism, self-sabotage. This is your psyche waving a red flag: your sense of self has become confused with your competence.

Even Toni Morrison—Toni Morrison!—doubted whether she was as good as others claimed.

This uncertainty about success is tricky business because it forces us into business that isn't our own: trying to see ourselves through other people's eyes. Are we as capable as they think? Do we match the image they've projected upon us?

No. We never will, and it doesn't matter.

But we can't stop ourselves. We attempt to see ourselves through the eyes of people we don't know and have never met. We feel fraudulent. We fear discovery. We trap ourselves in a mental loop of our own making, imagining other people's expectations (usually getting them wrong), then measuring ourselves against those arbitrary, imagined standards.

Someone else in our field gets a huge fellowship, and we take it as evidence we're falling behind. Someone gets invited to a festival, and we assume we're not worthy. We exist in a world modeled on traditional benchmarks, so we create the metrics and expectations we imagine others have for us. Then we panic that we're not meeting them.

Not sure if membership is right for you? Spend a week inside the deeper work — full essays, archive, and more — and decide from within.

We measure ourselves by imaginary metrics regardless of where our self-worth actually lands. Those who experience success as luck or connections rather than ability live in constant fear of being found out. This is impostor syndrome—or impostor phenomenon, the preferred term.

An impostor pretends to be something they're not to deceive others. Someone with impostor syndrome fears being outed as a pretender, worries that people will feel deceived. It's the terror of fooling others because you doubt your own competence.

Impostor phenomenon is particularly crippling because embedded within it is the knowledge that everything is temporary. At any moment, you could be revealed and stripped of your audience's awe.

But here's what we forget: We can't control how people perceive us. Some elevate us, others underestimate us. We can never truly match anyone's expectation or perception of us, nor should we try. What matters is the standard we hold for ourselves and whether we're meeting it.

Living according to other people's standards is not living your life truthfully. It's—wait for it—living life as an impostor.

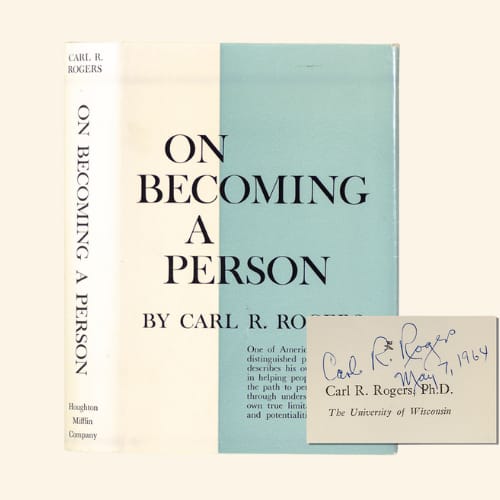

We are impostors only when we aren't being true to ourselves—a term Humanistic Psychologist Carl Rogers coined Congruence. We are not impostors when we fear others will expose us as frauds.

Here's what I think many of us miss: We all suffer from this. Every single one of us. At any moment, we're either pulling back from the next level of success because we fear we don't deserve it, or we've reached that level and are questioning whether we deserve it.

Self-doubt can find itself giving rise to self-handicapping behaviors like procrastination, perfectionism, and or other self-sabotaging behaviors. When this occurs, it’s a signal that your sense of self has become confused with ideas about your competence.

It never goes away.

So I wonder, returning to Laurie Anderson's words, whether our self-doubt isn't actually about competence at all. Perhaps it's about perception. Perhaps we fear being exposed not for being frauds, but for being unable to ever be who other people think we are.

Perhaps we've never been impostors. Perhaps we've simply been ourselves in a system designed to make us feel like we're not enough.

Trying to live up to other people's standards wastes your time. Trying to live up to the standards you imagine other people have for you is even worse.

Because the standards that truly matter are the ones we set for ourselves, and those standards aren’t fixed; they don’t need to stay the same day in and day out. The realistic goals we create for ourselves are the ones that matter. They conform to who we are and what we know we can achieve.

Try this: Write down your own standards and expectations. Then focus on meeting them. Not the imagined standards of invisible judges. Not the benchmarks of a system built to sort and classify.

Yours.

And You?

Do you suffer from self-doubt? In what ways have you felt fraudulent?

Let me know in the comments.

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade