The Science of Connection: What Four Decades of Attachment Research Reveals About Our Deepest Human Bonds

We're only as needy as our unmet needs.

What makes us cling to some people and push others away?

What shapes our ability to trust, love, and connect? For one answer, we can return to early 20th-century London, where a lonely boy named John Bowlby sat in a nursery, waiting for the person who made him feel safe.

John Bowlby was born in 1907, the fourth of six children in a British upper-middle-class family. His parents followed the rigid norms of the Edwardian era, where emotions were considered weaknesses and liabilities. His mother, dedicated to social propriety, met with her children for only one hour daily at tea. His father, a prominent surgeon, was even more distant, seeing the children only on Sundays.

Though John’s mother considered excessive affection dangerous, he found comfort in the warmth of his nanny, Minnie. But when John was four, Minnie left the household abruptly—a loss Bowlby would later describe as a “psychic wound.” The profound grief of losing his primary source of emotional security planted a question that would shape his life’s work: What happens when we lose the people who make us feel safe?

At age seven, Bowlby was sent to boarding school—a common practice among Britain’s upper class, despite its harsh psychological toll. Years later, he reflected: “I wouldn’t send a dog away to boarding school at age seven.” His own experiences with separation, isolation, and emotional neglect gave him an intimate understanding of the profound human need for connection. This need would form the foundation of Attachment Theory.

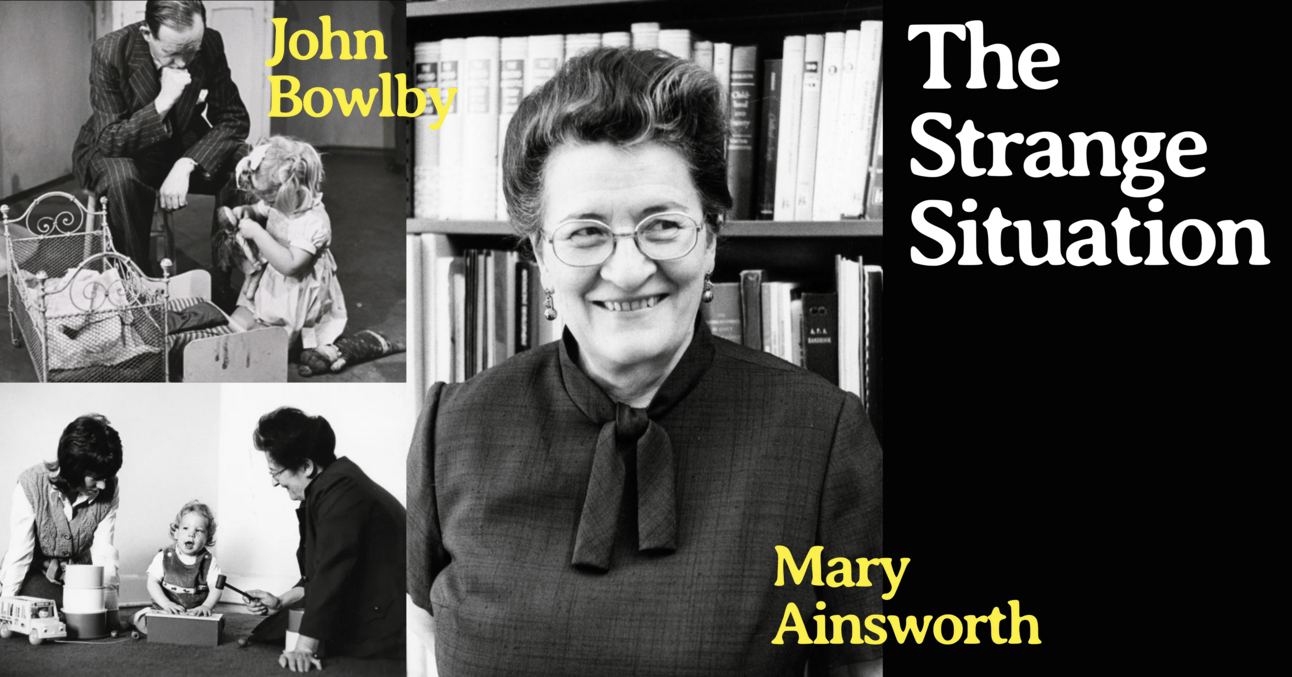

The Wellcome Library (2015) Dr. Bowlby observing a child at play. Wellcome Images reference: L0039184. London: The Wellcome Library.

In 1913, six years after Bowlby’s birth, another child was born far across the Atlantic in Ohio: Mary Salter (later Mary Ainsworth). A precocious child who taught herself to read at age three, she was intellectually curious but emotionally cautious. Her mother was distant, but Mary shared a close bond with her father, who nurtured her intellectual curiosity.

At age 16, Mary enrolled at the University of Toronto, determined to study psychology. After earning her doctorate, she became fascinated by human relationships, particularly how early attachments shape future emotional security. This interest eventually brought her to London, where she worked alongside John Bowlby as a clinical postdoctoral researcher at Tavistock Clinic, where Bowlby created the Separation Research Unit in 1948.

If Bowlby is the father of Attachment Theory, Ainsworth is its mother—her contributions would become the bedrock on which the entire theory stood.

Mary Ainsworth | JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado

By the mid-20th century, Bowlby worked with emotionally troubled children in post-war London. He noticed a recurring pattern: children separated from their parents displayed behaviors ranging from despair to detachment. Many were unable to form meaningful relationships later in life. Was there a psychological explanation rooted in early separation?

Inspired by evolutionary theory, Bowlby argued that human attachment evolved to ensure survival. Infants form emotional bonds with their caregivers for love and survival—a deeply ingrained mechanism that provides protection and care. He outlined three primary stages of emotional response to separation: Protest, Despair, and Detachment.

His revolutionary ideas defied psychoanalytic orthodoxy, which viewed children’s bonds as driven purely by biological needs like hunger. Bowlby saw attachment as far more complex—a deep emotional bond critical to psychological development.

Bowlby certainly meant well, but some of his writings for women’s magazines, and in his books for a popular audience (like, the 1953, Child Care and the Growth of Love) were filled with farcical embellishments that served only to blame mothers who could not fulfill its bombastic claims that “…a young child needs their mother ‘as an ever-present companion’, providing ‘the provision of constant attention night and day, seven days a week, and 365 days in the year’. He’d intended to convey that children need a safe person to turn to when they feel afraid.

Though he later regretted this statement, steeped in pure prejudice and setting all women up for failure and blame, he couldn’t take it back.

While Bowlby built the theoretical foundation of Attachment Theory, Mary Ainsworth tested it scientifically. In the 1960s, Ainsworth conducted the now-famous Strange Situation Experiment at Johns Hopkins University. She aimed to observe how young children reacted to temporary separation from their mothers.

The experiment unfolded in a controlled setting, where infants were exposed to separations and reunions with their mothers and strangers. Ainsworth paid close attention to how the infants responded when their mothers returned. From these observations, she identified three distinct attachment styles:

To read the rest of this post and access the styles, you must upgrade.

Join How to Live

For people who live in their heads, feel more than they show, and want a language for both.

Every Essay, Every Time.What you’ll receive as a subscriber::

- Every new essay, the moment it’s published

- Full access to the complete archive—150+ posts and counting

- Bonus pieces and experiments-in-progress, shared occasionally

- Invitations to seasonal, in-person gatherings

- A direct line to me (annual subscribers): personal replies and tailored recommendations

- 15% off all workshops and live events