The Art of Catastrophizing Isn’t Hard to Master

In 2004, I had a six-week fellowship at MacDowell, an artists’ residency in Peterborough, New Hampshire. A few weeks before heading there, I moved in with someone I shouldn’t have.

After a blissful few days visiting me, he was driving back to Brooklyn from Peterborough.

The drive back was long—around six hours—but when I hadn’t heard from him after a few hours on the road, and my calls went straight to voicemail, I knew he was dead.

Of course, he was dead.

What other possible explanation was there?

That he was driving?

That he was getting gas?

That he was getting food, in a bathroom, at an outlet store because...WHO DOESN’T LOVE AN OUTLET STORE?!

You call those options?

He was dead.

I was inside the belief, already filled with grief and the sad ever-after that follows when a true love dies too young. Would I have it in me to speak at the funeral? Probably not. I’d also have to move. How would I afford a new place on my own? I would not survive this...

In cognitive parlance, the frothy state I’d whipped myself into is called Catastrophizing or awfulizing (a term that didn’t catch on, but I love it so much).

Catastrophizing is a cognitive distortion—an irrational or harmful thought pattern causing a misperception of reality—that leads a person to jump to the worst possible conclusion based on limited, often subjective, information. It’s a common symptom of anxiety disorders and clinical depression, typecast as the trusty antagonist that comes in to make things worse when things could go either way.

Later, after he called back to reassure me that he was not dead, I reflected on the moment. I recognized my impulse to skip the rational middle and jump straight into the disaster of the irrational. I’d been doing it my entire life.

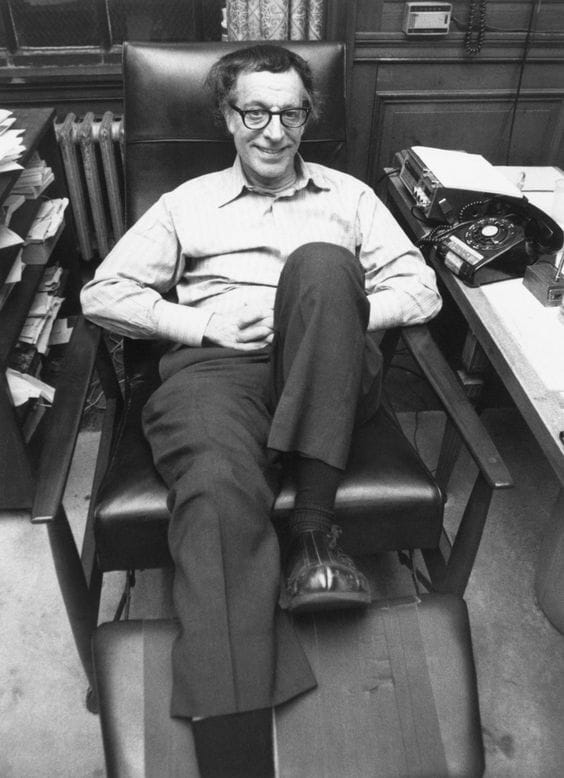

The renowned psychologist Albert Ellis (1913–2007) believed irrational thinking patterns were at the root of most psychological problems—he coined the term catastrophizing.

Albert Ellis

In the 1950s, he pioneered a form of cognitive therapy, initially called Rational Therapy and later known as Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), to help his patients improve their emotional well-being more quickly. Ellis’s action-oriented approach to confronting and changing irrational beliefs laid the groundwork for Dr. Aaron Beck and what is now known as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Catastrophizing is common among people with anxiety disorders—whether social, generalized, panic, agoraphobia, or OCD—and it’s also associated with anger-related problems and depression (lest you feel excluded).

However, you don’t need to have a mental health disorder to catastrophize. Anyone can be a catastrophizer—join us! (No, don’t.)

Anxiety is often described as the tendency to overestimate threats while underestimating one's ability to cope with them, resulting in increased worry. A fine loop, indeed.

But what underscores it?

To dig in, trace back the roots, and find where catastrophizing began, how it works, and how to dismantle it, click the upgrade button and read the rest of the piece, after the jump.

Join How to Live

For people who live in their heads, feel more than they show, and want a language for both.

Every Essay, Every Time.What you’ll receive as a subscriber::

- Every new essay, the moment it’s published

- Full access to the complete archive—150+ posts and counting

- Bonus pieces and experiments-in-progress, shared occasionally

- Invitations to seasonal, in-person gatherings

- A direct line to me (annual subscribers): personal replies and tailored recommendations

- 15% off all workshops and live events