GET READY, FOLKS, this is a looooooooong one, but it just might get you through the Thanksgiving holiday.

The first section concerns Aaron Beck's childhood ("The father of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy" or CBT).

The middle section is about Beck finding his focus as a medical practitioner and how he discovered CBT.

The third section will deliver the practical goods.

There are PLENTY of resources at the end of this piece, including downloadable worksheets and a free sample chapter of David Burns’s excellent book Feeling Good about Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, from which many of the techniques in the end originated.

Here we go…

Today's newsletter is about Aaron Beck, the Emily Post of Thinking. Dr. Beck discovered how to teach unruly minds to behave with proper etiquette, "mind" their manners, and stop acting like unshowered and UNINVITED houseguests who have overstayed their welcome since the second they arrived unannounced.

He called it Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT.

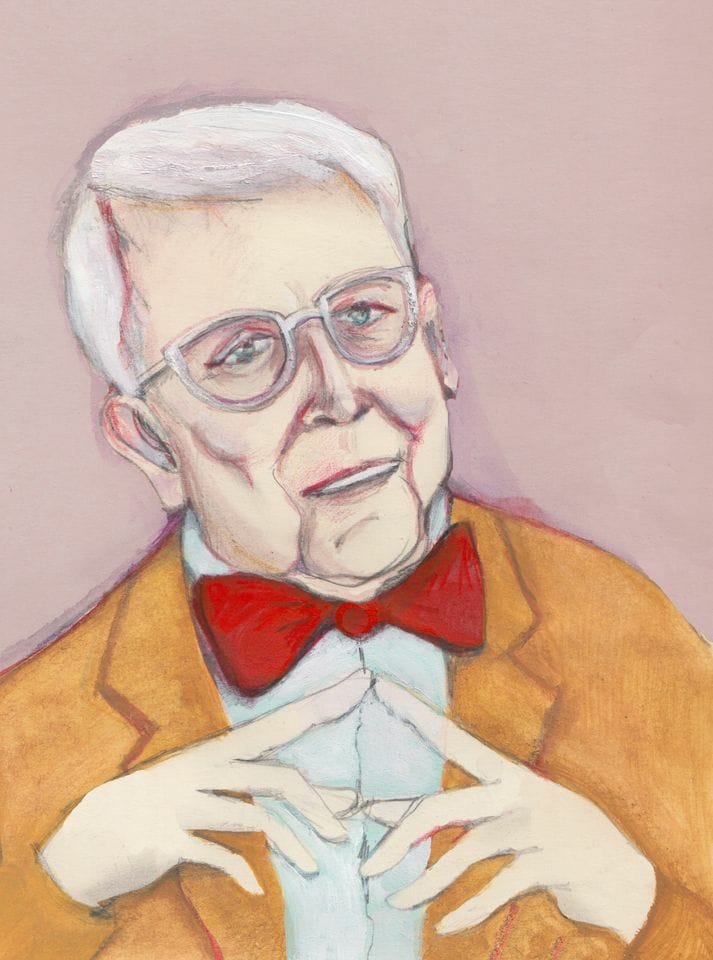

Original drawing of Aaron T. Beck by Edwina White

AARON BECK, the psychiatrist who died on November 1, 2021, at the age of 100, is considered one of the five most influential psychotherapists since Freud—and not just in my household.

Dr. Beck changed the face of American psychiatry and is the reason that so many of us who struggle with mental anguish (I am NOT a fan of the term “mental illness” and will write about that another time) are not simply standing, but thriving in ways we honestly never believed we could.

His contribution to psychology and mental health will outlast him by centuries.

Known as the “Father of Cognitive Therapy,” Aaron Temkin Beck—called Tim by his close friends and family, and ATB by his colleagues—was born in Rhode Island to Jewish Russian immigrants in 1921, the youngest of five children and arriving two years after his parents lost two children amid the influenza pandemic.

His mother, who suffered from mood swings, was still grieving her lost babies and remained profoundly depressed when Aaron was born. Beck’s mother was loving but fiercely and understandably overprotective after losing two children.

As he became more consciously aware of his place in his family, he became convinced that he was a replacement for his sister, who died in 1920, the year before he was born—he believed his mother was disappointed that he’d not been born a girl.

As a young boy in Rhode Island. From Aaron T. Beck's Facebook Page

Despite suffering from chronic asthma, Beck was a typically active young child, a Boy Scout who spent most of his time outside in the woods or with friends playing sports.

His parents encouraged his interest in science and his love of nature. He credited these early explorations with bird watching, learning to identify plants and trees, and becoming a naturalist and a camp counselor as the origin of his curiosity about “what makes people tick; particularly what makes them happy or sad, and confident or insecure.”

Yet, like many children throughout the history of time, especially the outdoorsy types, he broke his arm when he was around 7—an injury that greatly impacted his quality of life. Instead of racing around with his friends and playing sports, he was relegated to more sedentary indoor activities, like reading (my favorite athletic sport).

To add injury to injury, because of his physical inactivity and perhaps the less sophisticated medical care of the time, Beck developed a near-fatal blood infection at the site of his broken bone and was immediately hospitalized.

But this early experience in the hospital proved to be a traumatic and formative one: Beck would learn much later that his blood infection had a 95% mortality rate, and that he’d nearly lost his arm to amputation.

He missed so much school that he was asked to repeat first grade while the rest of his friends advanced.

And, if things weren’t bleak enough, during one of his stays, the surgeon began his incision before young Beck was fully anesthetized, triggering the first cascade of several phobias—hospitals, surgery, blood injuries, and the smell of ether.

Because of the severity of his injury, he understood that he’d not be able to avoid hospitals, and all the attendant sights, sounds, and smells. So this young stoic decided on a rational approach—he’d treat it himself. "I learned not to be concerned about the faint feeling, but just to keep active,” Beck was quoted in a New York Times profile. Through exposure and willpower, he slowly faced his fear of hospitals.

He would soon discover how to use his resilience as fuel to conquer his demons.

How’s that, you ask?

Let’s carry on, we’re getting there…

My most profound insights don't go in the free version—they're distilled from my 27 years in therapy, decades of independent study, and work as a mental health advocate. These deeper dives are reserved for readers committed to going deeper.

Join How to Live

Transformative concepts from a lifetime in therapy.

Get Immediate AccessA subscription gets you:

- All articles the moment they're published

- Instant access to the entire archive of 150+ posts

- Occasional bonus posts

- Invitations to seasonal in-person events

- Direct email access: get personalized resource recommendations + advice (ANNUAL PLAN ONLY)

- 15% off all workshops