TL;DR is a monthly digest summarizing the vital bits from the previous month's How to Live newsletter so you don't miss a thing.

JUNE 2025

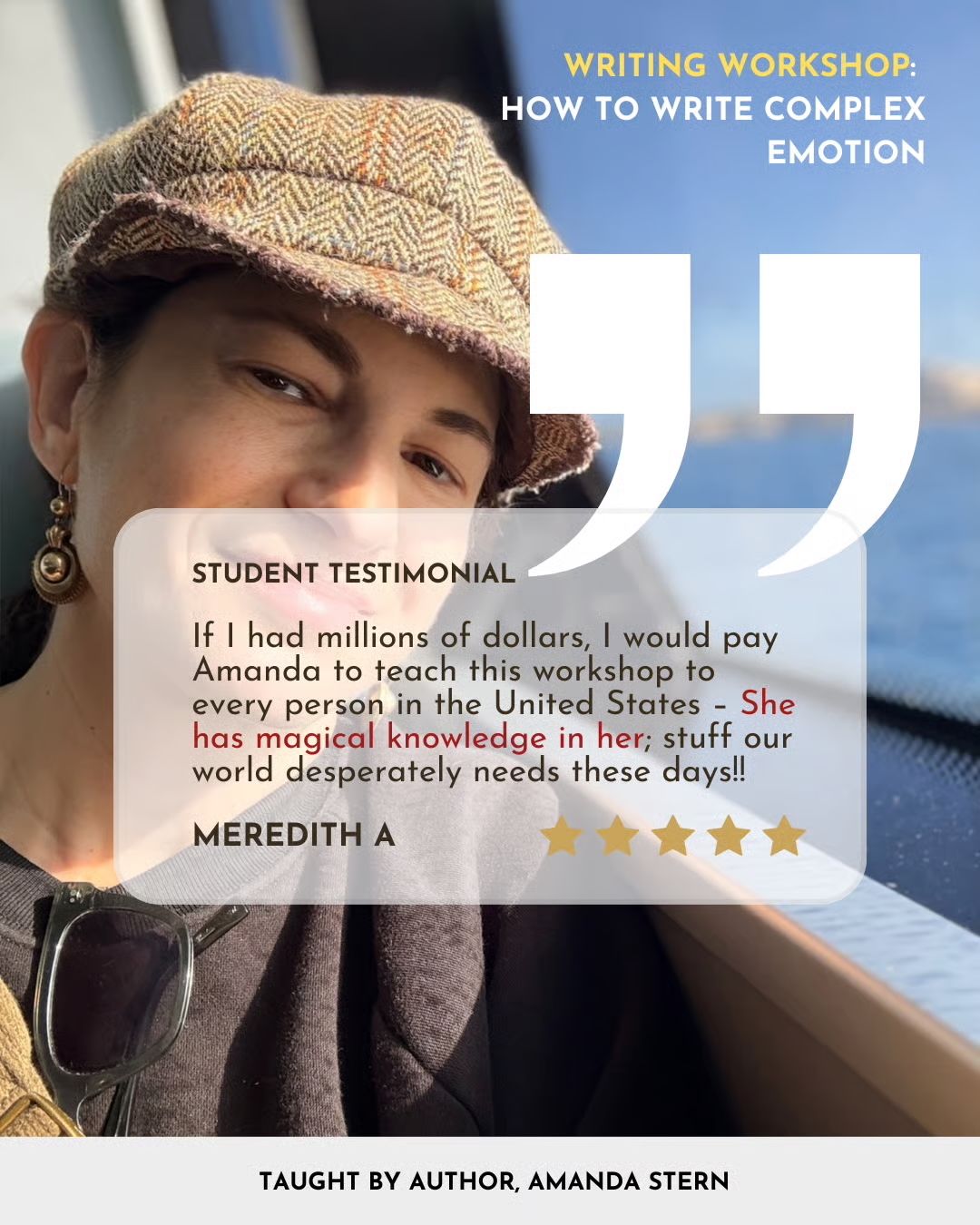

Today is the last day you can sign up.

2 Sessions: Monday + Tuesday, July 14 + 15

6:00-8:30pm ET

Highlights:

Embodied Emotional Access: Learn how to identify and access emotions through the body, using somatic awareness to uncover authentic emotional content.

Language for the Inexpressible: Gain practical tools for translating nuanced, internal experiences into language that resonates deeply with readers.

Atmospheric Emotion: Develop techniques for infusing emotion into setting, tone, and subtext—creating immersive, emotionally charged scenes without overwriting.

On June 4, 2025, I Wrote About The Unbearable Lightness of Being Disliked.

In 1902, Sigmund Freud sent an invitation to the Austrian psychotherapist Alfred Adler:

A small circle of colleagues and supporters afford me the great pleasure of coming to my house in the evening (8:30 p.m. after dinner) to discuss interesting topics in psychology and neuropathology....Would you be so kind as to join us?

Upon his acceptance, Adler became a member of “The Wednesday Psychological Society” (later the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society), whose ideas would eventually become known as modern psychology.

But by 1912, Adler broke away.

Freud was pulled inward—obsessed with the subconscious, with drives and instincts and unresolved childhood conflicts. His lens was microscopic, intimate, intrapsychic.

Adler, on the other hand, looked outward. He saw that a person cannot be understood in isolation. We exist in systems: family, culture, class, school, work, history. For Adler, the human condition wasn’t just internal—it was social. Personal problems, he believed, were always interpersonal.

His belief in change foreclosed on fate, determinism or pathologies as destinies.

More than a hundred years later, Adler’s ideas have been resurrected in a book that’s quietly reshaped the way millions of people think about identity, self-worth, and belonging:

Through a philosophical dialogue between a teacher and a skeptical student, and based on the Socratic Method, the book introduces Adler’s concept of Individual Psychology—a growth-based approach that rejects determinism and asks us to stop living according to other people’s values.

The Courage to Be Disliked: The Japanese Phenomenon That Shows You How to Change Your Life and Achieve Real Happiness by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga has sold over 3.5 million copies—nearly outselling my own book Little Panic: Dispatches from an anxious life (this is a joke, for anyone new to how I operate).

Despite its deceptively gentle tone, the book makes an urgent case:

If you spend your life trying to be liked, you will never be free.

If your worth depends on the approval of others, you will never feel whole.

We confuse being liked with being safe. We confuse pleasing others with knowing ourselves.

But here’s the catch:

We are evolutionarily wired to care what people think.

Our brains are tribal. Our nervous systems are social. In prehistoric times, exile meant death. To be cast out from the group was to die alone in the wilderness. That fear didn’t vanish—it evolved.

The stakes may be lower now, but the fear is just as sharp.

Adler understood this. But instead of pathologizing our fear of rejection, he gave us a new way to live with it—a way to separate ourselves from the entanglements of social pressure without losing our place in the human community.

And it starts with a single, powerful question…

On June 11, I Wrote About The Unspoken Grammar of Love

John Gottman, one of the country's leading relationship experts and founder—alongside his wife, the esteemed psychologist Julie Gottman—of the famed Gottman Institute, has spent decades studying the architecture of romantic breakdowns.

But he didn't set out to do that.

Born in 1942 to Orthodox Jewish parents in Brooklyn, he originally studied mathematics at MIT, drawn to the clean logic of equations. Still, the question he’d spend his life trying to answer tugged him elsewhere: Why do some couples make it while others don't?

By the 1970s, Gottman had pivoted to psychology. Alongside psychologist Robert W Levenson, he created the Love Lab—an apartment outfitted with cameras, microphones, and biometric sensors—where real couples lived for a weekend as researchers observed every micro-expression, gesture and interaction.

Gottman and his team coded these interactions with mathematical precision, tracking heart rates, stress hormones, and the exact words couples used when they fought about money or sex or whose turn it was to take out the trash.

What he discovered was revolutionary.

On June 18, 2025 I Answered Readers’ Questions.

No matter our differences, there is one thing we all share: PROBLEMS.

And today, after a call to readers to ASK ME ANYTHING, I'm bringing you answers to some of yours.

They might be the wrong answers, but they're still answers.

At the very end, as a special treat, I share the best of the best advice How to Live readers have been given.

Today, it's all about YOU—the best subscribers on the planet.

June 25, 2025 I Wrote About Th

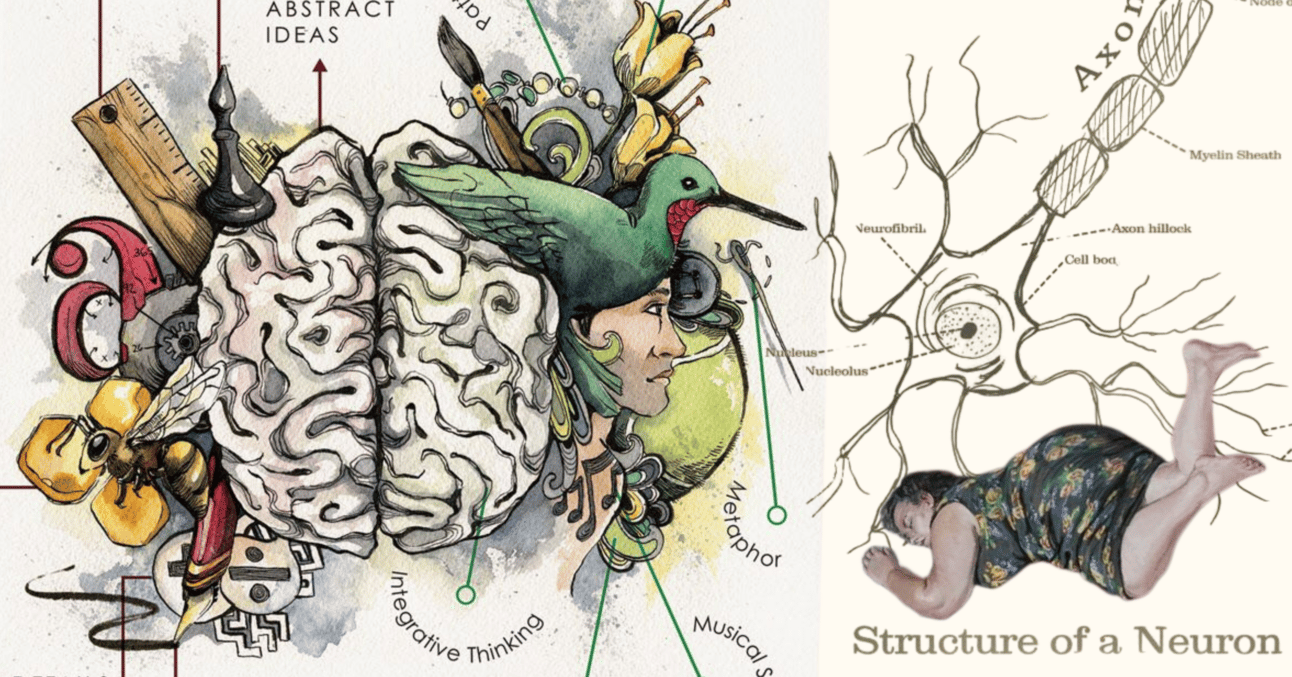

On my bedside table sits a handwritten reminder: The brain takes the shape of what the mind rests upon.

This principle, rooted in Buddhism, is also the foundation of neuroplasticity: our thoughts alter the physical structure of the brain.

Say what?

Yup.

What you think and do repeatedly can literally influence the physical structure of the brain. The brain you're born with continues changing throughout your life.

When you learn something new, neurons (brain cells) form new connections. In some brain regions, your brain may even create new neurons through a process called neurogenesis.

From a vintage textbook called “Biology; the story of living thing.”

Remember Newton's third law of motion? For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction?

Your brain operates on a zero-sum budget. When you get obsessed with piano, it doesn't just build new networks for finger coordination and musical processing—it starts pulling resources from the motor skills you're neglecting. Those pathways get weaker while the piano ones get stronger.

Neuroplasticity is your brain's constant rewiring project. It's always forming new connections and adapting to whatever you're doing most—learning, practicing, even recovering from injury. But it aso adapts and strengthens connection to your most recycled thoughts.

The mechanics: Neurons communicate through synapses, and repeated activity strengthens these connections. Scientists call this Hebbian plasticity—"neurons that fire together, wire together." Every time you practice something, you're literally reinforcing those neural networks.

But there's a catch—brains are efficient, not ambitious. They follow established pathways and shut down the unused ones. Left to their own devices, they'll take the path of least resistance every time.

The upside? We can direct this process through our choices. What we practice and choose to believe is what gets consistently reinforced.

Discover a handful of principles from neuroscience that can help you work with your brain's natural adaptability—and influence who you become.

Thank you for subscribing!

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade