TL;DR is a monthly digest summarizing the vital bits from the previous month's How to Live newsletter so you don't miss a thing.

JULY 2025

This newsletter is my life and my livelihood. If How to Live matters to you, please help me keep making it. Become a paid subscriber—or make a recurring or one-time donation—to say: this work matters, keep going. 🙏

On July 2nd, 2025, I Wrote About Becoming a Person

There exists a particular form of suffering that, while identified by psychology, remains largely unrecognized in our daily discourse: the quiet torment of living among people whose words bear no reliable relationship to their actions; who say one thing but do another. We have a clinical term for this phenomenon—incongruence—yet we lack a cultural vocabulary adequate to its emotional reality.

The concept belongs to Carl Rogers, a founding figure in humanistic psychology who, in 1950, was trying to understand what made some therapeutic relationships transformative while others fell flat.

Carl Rogers

What he discovered, however, was the fundamental mechanics of human trust.

When Solomon Asch was a 7-year-old in Poland, he was finally allowed to stay up late to experience his first Passover dinner with his family. As his grandmother poured a second glass of wine, Solomon asked who it was for. “For the prophet Elijah,” his uncle said.

"Will he really take a sip?" the boy asked.

"Oh, yes," the uncle replied. "You just watch when the time comes."

That suggestion and expectation filled Solomon with enough conviction that he watched the glass carefully. After a while, he realized that the level of wine in the cup had gone down. At least, that’s what he believed.

That single experience set the stage for Solomon’s life’s work as a social psychologist, pioneering studies highlighting how peer pressure shapes human behavior.

As a grown man, now living in NYC and teaching psychology at Brooklyn College, World War II began to take shape, and as Hitler rose to power, Dr. Asch began studying the effects of propaganda and indoctrination.

He found that propaganda is most effective when coupled with fear and ignorance. Instead of seeking out what might be false about the information we read and hear, the human mind is primed not to look for falsehoods but for truth, especially when the information is being disseminated by a majority group.

We are highly suggestible, and because we often believe what we’re told without doing our due diligence, he learned that people will often do regrettable things just to fit in—even if they don’t realize that’s why they’re doing it.

On July 16, 2025 I Wrote About Some Things I’m Loving

Everything feels like it’s too much—I know I’m not alone here—and at the edges of this too muchness is a gnawing loneliness, an isolation so acute, it’s tugging my hair at the nape, trying to yank me toward depression.

But, I’m pushing back.

Mainly by over-indulging in good-for-me content, a healthier avenue to numb and distract myself from the horrors of the world, and the downfall of America.

Here are a few things I’ve been consuming that I think you might appreciate.

BOOKS

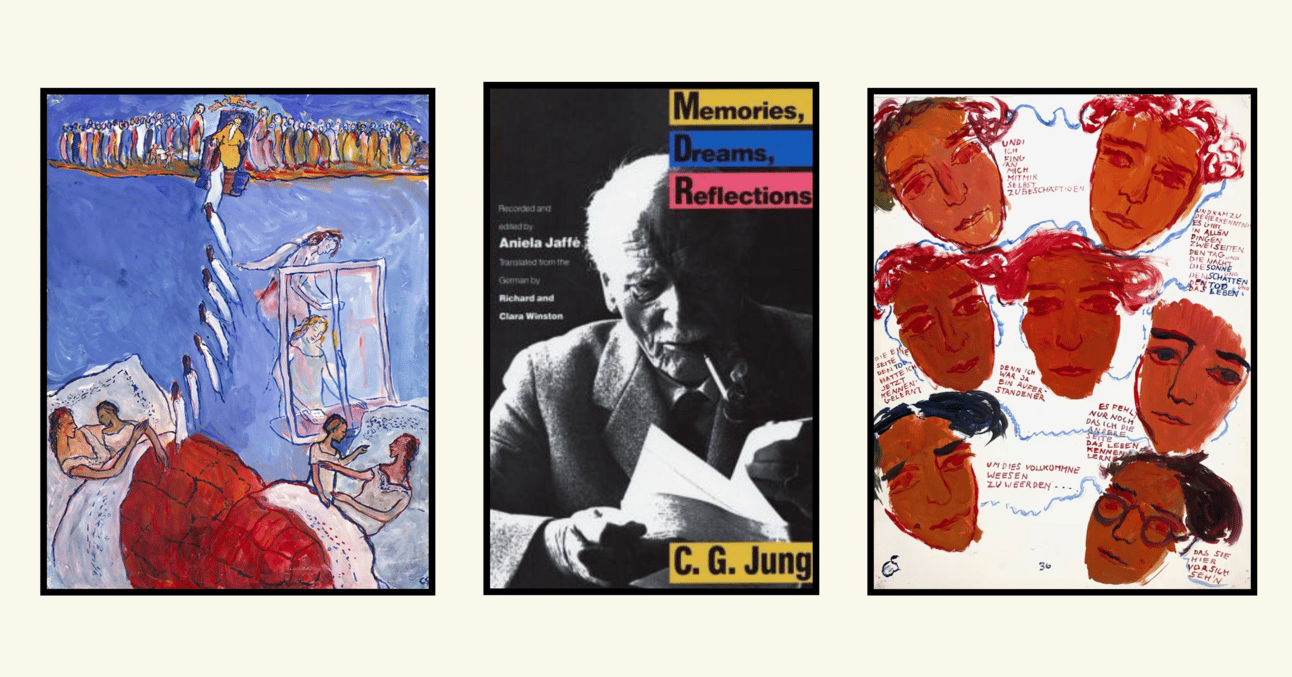

In 1957, at the age of eighty-one, Carl Jung began writing the story of his life.

The result is less a conventional autobiography than a psychological and philosophical memoir—a rich excavation of his inner world. Jung traces his early childhood, his break with Freud, and the evolution of his theories on the unconscious, archetypes, and the symbolic language of dreams. The tone is often mystical.

Rather than cataloging external achievements, the book offers an intimate tour through the landscape of Jung’s psyche—a life within a life—marked by depth, insight, and the uncanny feeling of inhabiting someone else’s inner world.

On July 23rd, 2025 I Wrote About When You Feel Out of Place in the Human Condition

There are people—perhaps many—who never seem to find a place that suits them.

No ideal environment. No space where the inside of them matches the outside world.

They have friends, they're sociable, intelligent, and even charming. But no matter where they go, nothing feels like "home," and no one feels like "their people." It's not just about physical distance; something inside them never quite aligns with what's around them.

They wait in vain for the matching click of recognition—the moment their deepest interior need is met by the external world.

They're not exiles, not precisely. No one's cast them out. But they carry the ache of never quite fitting, of always feeling a little off-center.

They feel like strange punctuation marks—people recognize their shape but can't quite figure out the rules.

Loneliness for them isn't about the absence of people; it's about the absence of connection in the presence of people that feels most acute. They might not be alone at a holiday dinner, but they're alone in their experience of their aloneness.

They live with the loneliness that becomes, over time, ambient noise. The background soundtrack to life. Often, it feels like living on a different frequency from everyone else.

They might be in a room where friends talk about the regular things they all do together—poker night, a dinner club, something—and no one thinks to include them, even though they're right there. No one says why. But they feel it. They become used to exclusion, even if they don't understand it.

They don't feel entirely misunderstood—they feel half-understood by almost everyone.

Mostly, they feel forgotten.

They don’t struggle with the nature of their identity, but with the existential nature of existence.

They often doubt their own reality. Maybe they’re just difficult. Or their needs are too specific. They assume this loneliness is their fault.

But really, it’s a matter of ontology. Of the way culture, community, and family have become siloed. Their psyche mourns for a world that no longer remains; they long for something they never experienced.

Our culture lacks the language for this. Because our culture created it.

So, how do they keep going?

On July 31st, I Wrote About What We Mourn When We Mourn A Celebrity

Like many, I grew up listening to the satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer.

He was one of my father's favorites. While they never met, they shared a history: Lehrer was a camper and then a counselor at the summer camp my dad attended (Stephen Sondheim even had him as a counselor), and they both attended the same high school, albeit fifteen years apart.

Lehrer was a child prodigy. At fifteen, he applied to Harvard with a poem and was admitted; he graduated summa cum laude at eighteen. On the weekends we spent with our father, we'd always end up in "the green room" to listen to his albums, singing along and knowing he was funny, even if we didn't always understand what he meant. Our dad loved it when we sang along, and we loved making him laugh.

Over time, Tom Lehrer became a concrete way to bond with our father—whom we saw only four to six days out of every month. Through Lehrer, we learned that laughter can be a form of intimacy, and that wit always won the day. Even when we weren't with our father, Lehrer's music was a way to be with him.

When I was in high school, Malcolm-Jamal Warner entered my life as Theo Huxtable on The Cosby Show. We were close in age, and while many of my friends were obsessed with the stunning Lisa Bonet, I watched Theo, whose mistakes and learning challenges resonated with me. Though we were of different genders, races, and lived in families that couldn't have been more different—his sitcom-stable, mine crowded and chaotic—I felt a kinship. He modeled a version of adolescence that seemed whole, survivable.

On July 20, 2025, Warner drowned while on a family vacation in Costa Rica. He was only 54 years old. Six days later, Tom Lehrer died at ninety-seven. Two very different men, linked only by the fact that both had been players in the shape of my youth.

I never met either of them. Neither knew I existed. And yet I felt genuine sorrow when they died.

Why do we mourn celebrities—people we never knew?

Thank you for subscribing! If you like this newsletter, please share it with friends!

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade