Hi {{ First Name | friend }}!

TL;DR is a monthly digest summarizing the vital bits from the previous month's "How to Live" newsletter so you don't miss a thing.

JANUARY 2024

The piece from January 3rd, 2024, Was About Naive Realism, or the Phenomenon of Believing Your Subjective Truth is Objectively Right.

At the heart of naïve realism is a false belief that we experience things exactly as they are, that the world is a material object. We fail to recognize that there is no “exactly as it is.”

Different circumstances and experiences shape every person (and maybe every animal?). We have separate histories, emotions, and cultural biases. Different things and people have influenced us, and all those things combine to create and shape our point of view.

Often, when things FEEL true, we struggle to understand how these same things might not feel true to others.

We assume the ability to identify objects means we are unbiased about them instead of understanding that it’s not objectivity through which our world is mediated but subjectivity, built and shaped over our lives by our personal experience, family customs, and surrounding culture.

This piece from January 10th, 2024, Was About Childhood Separation Anxiety.

When my memoir, Little Panic, came out, I spent over two years on a book tour and did many podcasts.

I have several I love, and this one with the child psychologist Natasha Daniels (whom I’ve mentioned before) is one of them.

I share it now because it’s an excellent preview of things I discuss in the digital workshop The Little Panic Approach to Supporting Your Anxious Child, but also because it’s a natural leadup to a piece I’m working on now that is, perhaps, the most personal How to Live piece I’ve ever written.

I hope today’s video resonates with you.

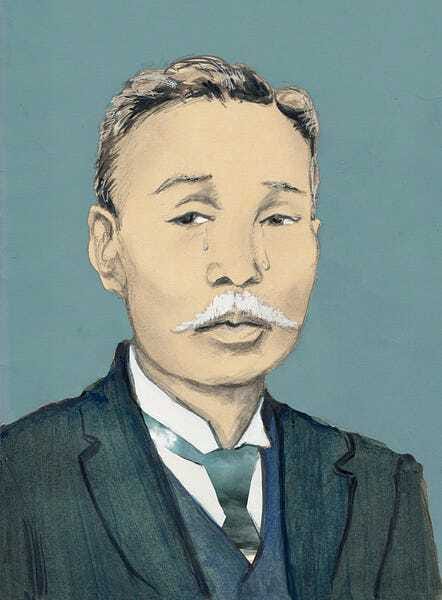

The January 17th piece was about The 3 Rules of Morita Therapy, the 100-Year-Old School Founded by Dr. Shoma Morita.

In the early part of the 20th century, when Freud was consciously coupling with the unconscious mind and Jung was creating his archetypes, Dr. Masatake (also known as Shoma) Morita, the head of psychiatry at Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo, was developing his psychotherapeutic methods with roots in Zen.

Dr. Morita worked with people suffering from anxiety and mind-body disorders. The name in Japanese for those who suffer from anxiety disorders was shinkeishitsu (which, like the word “neurotic,” is now outdated). A dedicated practitioner, Dr. Morita developed his therapy to address these issues with those patients.

Dr. Morita understood that we live in a paradoxical existence. We want to feel emotionally comfortable and at ease while also wanting to enjoy successful careers, deep and meaningful love, and have families and nurturing friendships.

Achieving any of the latter requires sacrificing the former. One cannot go after one's dreams without pressing up against feelings of discomfort and vulnerable emotions.

And because these sensations are so wildly unpleasant, many of us suppress or avoid the things that give rise to uncomfortable truths. It’s this dysfunctional reaction to psychological suffering that keeps us stuck in place.

To truly know ourselves and others requires the emotional discomfort of facing our insecurities, inadequacies, fears, desires, doubts, and traumas.

This piece from January 10th, 2024, a Q&A on Ontological Insecurity, was a Bonus Post for Paying Subscribers.

Ontology is a branch of metaphysics focusing on the nature of being.

The concept of Ontological Insecurity, which emerged from existential philosophy (and through the work of R.D. Laing), refers to a profound sense of self-doubt and a lack of confidence in one's identity and abilities. At its core, it points to the destabilization of the basic security we feel in who we are and our purpose.

Typically, this originates in disruptions to attachments in infancy and childhood.

When parents or other primary attachment figures can’t provide the emotional mirroring that infants and young children need to form a coherent, integrated self, this lack can lead to an incoherent sense of self that’s often carried through life.

Uncertainty about the stability of one’s existence and the contents of personhood becomes more common when this early attunement is lacking.

Those wrestling with high ontological insecurity frequently feel unsure if their outward presentation aligns with the inner truth or if something fraudulent exists at the core.

People with ontological insecurity long for the substantiveness their early environments could not nurture.

However, healing this distress is absolutely possible by creating the missed attunement, which I touch on in my answers below.

The January 24th piece was About The Hidden Force That Controls Our Self-Worth—Social Comparison.

Are you talented, attractive, or intelligent?

Whether you responded yes or no, the question remains: What measures did you use to gauge your assessments?

Humans have an innate drive to assess our own abilities, beliefs, and emotions, but without objective benchmarks, we evaluate these qualities by comparing ourselves to people around us.

This idea that we compare ourselves to others to gauge our abilities and worth is called Social Comparison Theory and was developed by psychologist Leon Festinger in 1954.

According to Festinger’s theory, we assess our abilities and attractiveness through comparison, which helps shape our self-worth.

Without being fully cognizant, we depend heavily on friends, neighbors, celebrities, etc, to determine how good we are at anything. Our social comparisons serve as barometers through which we develop notions of our overall adequacy and worthiness.

To resolve the inconsistency, the person is motivated to reduce the dissonance by altering their thoughts, beliefs, or behaviors. (Smoking is a great example of cognitive dissonance. We know it kills us, yet we don’t stop smoking. To explain this away to ourselves, we must convince ourselves that smoking may kill us, but it won’t kill us.)

The relationship between cognitive dissonance and social comparison is tight-knit: Social comparison provides contradictory information that can create dissonance, and the discomfort of that dissonance leads to more social comparison that leads to the discomfort we must resolve by reducing the dissonance. Oof, what a ride.

The January 31st piece was About The Invisible Inheritance of Childhood Emotional Neglect.

That’s the paradox of being a person.

We cannot see what we cannot remember or point to the moments that formed our worldview, our sense of safety and self, or our understanding of the matrix whose intricate and specific entanglement forms the scaffolding upon which we were raised.

We become the consequences of what was done to us and what was withheld.

The invisible map of our lives we follow is paved with unnamed feelings, leading to a routeless effort to meet our own needs without knowing what we need or why. We believe we know what we are seeking, although we are often wrong, and instead of living our lives, we’re stuck, like a trapped Roomba, within invisible parameters that we can’t name or see beyond and, therefore, cannot pass.

We are, each of us, caught in a world of unintentional consequences born from the missteps of those who raised us.

The wounds of childhood run deep.

This piece outlines the nine signs you may have suffered from Childhood Emotional Neglect and the manifestations of struggles typical in adulthood.

EXTRAS…

Sign up for my 7-part workshop…

The How to Live merch store is now open!

If someone sent this to you, please sign up to receive these weekly newsletters!

Amanda