December 2025

TL;DR is a monthly digest summarizing the vital bits from the previous month's How to Live newsletter so you don't miss a thing.

On December 10th 2025, I Wrote About The Most Important Parenting Question You've Never Been Asked.

Years ago, I took a friend's child to the library. One table over was a young mother with her son, around four years old. The librarian was helping them, and the mother was practically levitating with pride because her child was already reading.

As the librarian handed them the book they'd wanted, the mother opened it and said, "Show her how you can read!"

But the child didn’t want to, and shook his head no.

"Come on, show this nice lady how smart you are!" The mother looked at the librarian. "He really can read," she insisted.

The librarian bent down to the child and said, “It’s okay. You don't have to read out loud if you don't want to."

"No, he really can. I promise!” Then she sort of hissed at the boy, “Show the lady you can read.”

The boy looked terrified.

When the mother realized other people were watching, she doubled down instead of dropping it, announcing to the entire floor that her son could read.

Most likely, she thought she was praising her child. What she was actually doing was apologizing for her child being exactly who he was.

isabelle arsenault

For a person without children, I’m asked for parenting advice more often than you’d think.

By way of advice, I ask one question:

Are you raising the child you have, or the child you want?

To answer that, you first need to answer another question…

On December 17th, I Wrote About How to Think About How We Think

It’s late 1941, and seven-year old Daniel Kahneman has stayed at a friend’s house past curfew. Before he hurries home through the empty streets of Nazi-Occupied Paris, he turns his sweater inside out, hiding the yellow Star of David sewn to the front.

When a German soldier in an SS uniform spots him on the street, and beckons, Daniel is terrified he’ll make out the yellow star through his sweater. But instead of arresting him, the soldier picks him up and embraces him. After putting him down, the soldier speaks to him in German, and with great emotion, opens his wallet to show him a little boy, about his age. The weepy Nazi then hands him money from his wallet, and sends him on his way.

That moment would shape the rest of Daniel Kahneman’s life.

As he’d say later, "I went home more certain than ever that my mother was right: people were endlessly complicated and interesting."

That moment of cognitive dissonance—the recognition that a Nazi soldier could be moved by paternal love even as he participated in the wholesale murder of other people’s children—planted the seed for one of the most revolutionary discoveries in modern psychology.

And what he would go on to discover flipped what we understood about thinking on its head.

On December 24th, 2025 I Wrote About A Forgotten Management Technique That Reveals Our Blind Spots

In 1955, two American psychologists, Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, were working at UCLA's Western Training Laboratory in Group Development (now defunct and I’m unable to find any meaningful information) when they decided to develop a model to address a problem they'd observed in group settings.

People were consistently misjudging how others perceived them. Some believed they were coming across as confident when the group experienced them as defensive. Other people thought they successfully concealed their anxiety when it was obvious to everyone else they hadn’t. (I’m taking this one personally 🤣)

Luft and Ingham saw how these discrepancies between self-perception and others' perceptions was actively undermining group functioning. Their challenge wasn't just making people aware they had blind spots, it was creating a practical method that could reveal these misalignments without triggering the defensiveness that leads people to reject accurate feedback about themselves.

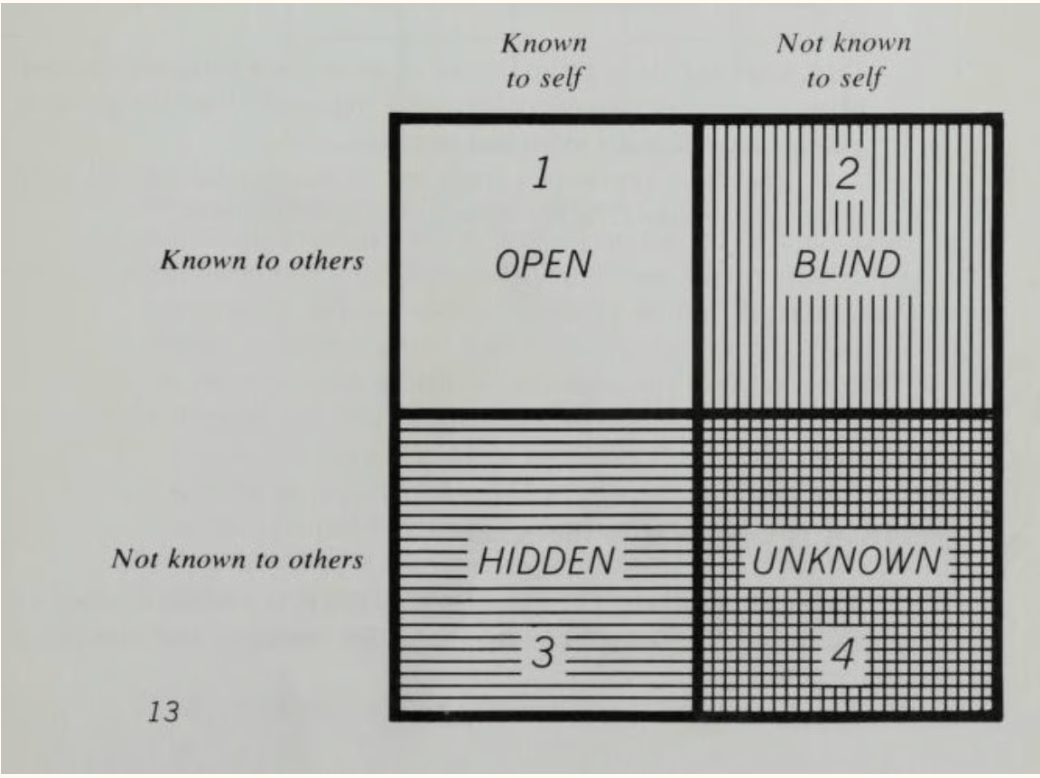

The model they created, later called The Johari Window (a combination of their first names) divided interpersonal awareness into four quadrants: what's known to both self and others (open), what others see but the person doesn't (blind), what the person hides (hidden), and what remains unknown to everyone (unknown).

They developed a list of 55 adjectives from which a user chooses five or six to describe themselves and others. The goal was to expand the open area through feedback and disclosure, making hidden patterns visible in a structured way that groups could actually use.

Anyone can perform the exercise one-on-one or with a group.

Here’s how it works…

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade