Hello from 4300 km on Swiss Air, an airline I will never fly again.

It’s been an absolute daymare. TL; DR-ish: The Swiss rejected Busy from our connecting flight in Zurich claiming I didn’t have the proper documents (I did), that I hadn’t paid (I had), that taking a pet on board isn’t an option (it is), that I’d neglected to add her to my booking (I hadn’t), and on…

We made it onto the plane with 40 seconds to spare, where I am now writing this piece.

America is on fire, but friends, I cannot wait to return home.

LET’S DO THIS…

You’re reading The How to Live Newsletter, where we uncover the hidden psychological forces shaping our lives—and learn how to outgrow their influence.

Through deep research, personal storytelling, and hard-won insight, I challenge the myth of normalcy and offer new ways to face old struggles.

This work is reader-supported. If it speaks to you, consider a paid subscription for deeper insight, off-the-record writing, and seasonal in-person gatherings. ❤️

The Necessary Unknown: The Voynich Manuscript, Winnicott's Third Space, and Why We Need What We Cannot Understand

It is in the space between inner and outer world that intimate relationships and creativity occur.

In the library at Yale University, there is a book no one knows how to read.

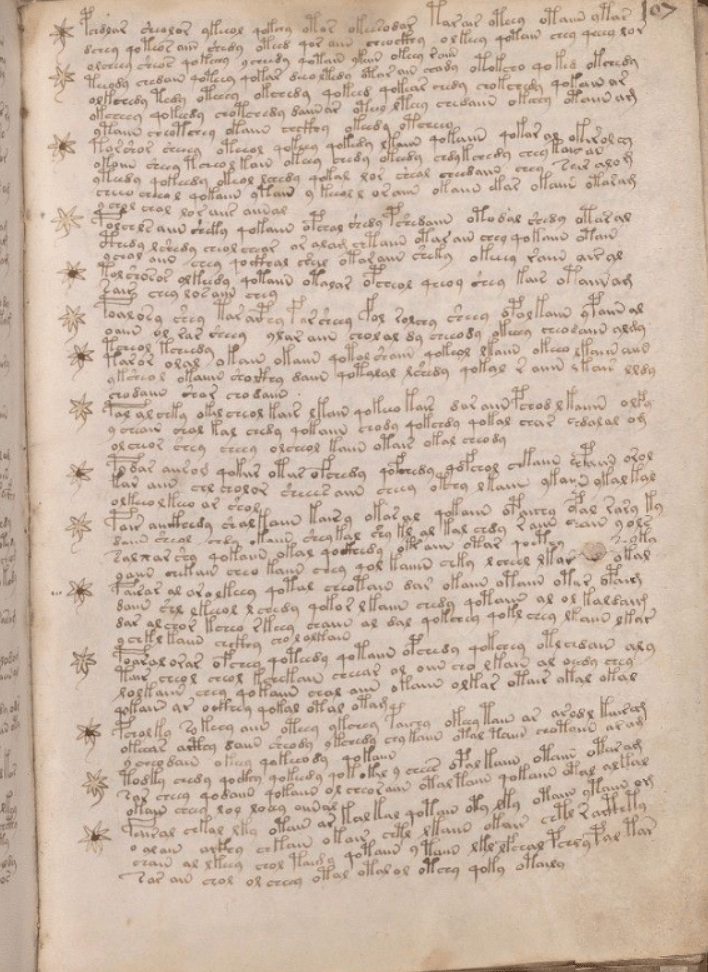

It sits behind glass, dates back to the early 15th century, and is written in an alphabet that appears nowhere else on Earth. For six centuries, not a single human being has been able to decipher a word of it.

No one knows if it contains prophecies, spiritual revelations, or scientific secrets, whether it's the world's most elaborate medieval prank or a more contemporary hoax perpetrated by the man who claimed to find this remarkable Codex.

Welcome to the maddening puzzle of The Voynich Manuscript.

Imagine spending your entire professional career—decades of specialized training in linguistics, cryptography, or medieval history—only to be thoroughly defeated by the work of an unknown scribe who's been dead for half a millennium.

This is precisely what's happened to generations of the world's brightest minds.

NSA cryptographers who cracked wartime military codes?

Stumped.

Linguists who can decipher ancient forgotten languages?

Baffled.

AI systems that can beat grandmasters at chess and Go?

Useless.

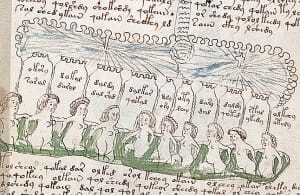

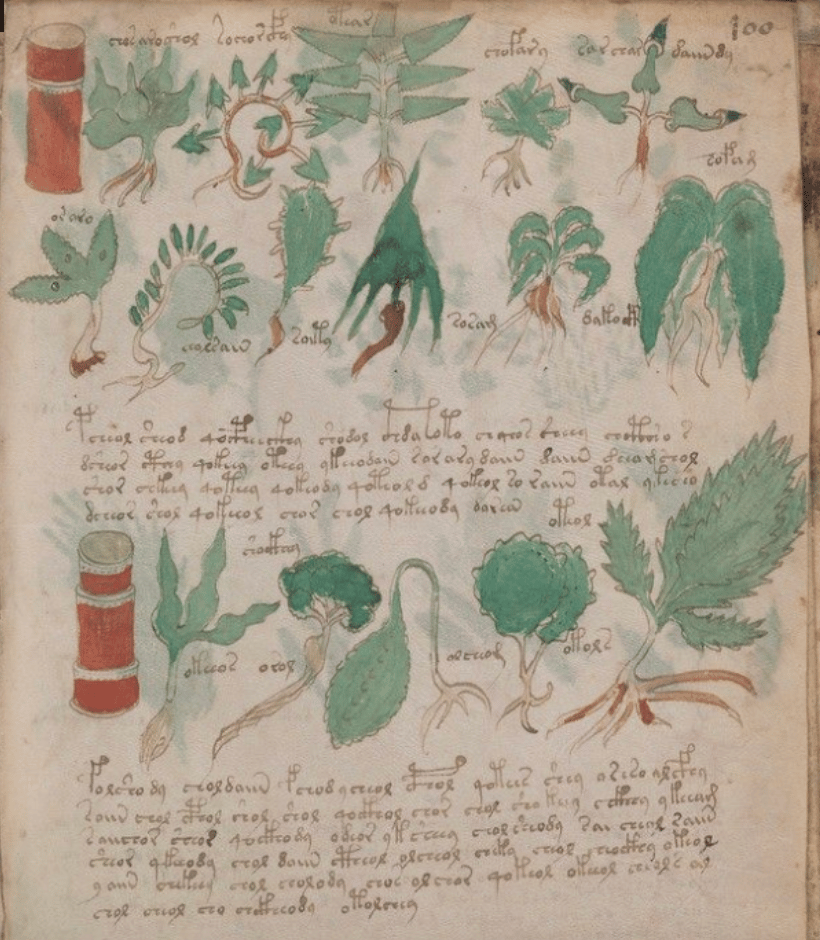

This perplexing manuscript, written on 240 vellum pages, contains illustrations of unidentifiable herbs and botanicals—the plants here resemble nature on an ayahuasca retreat.

What makes this centuries-old puzzle so infuriating isn't just that we can't read it—it's that it looks like we should be able to.

The text displays all the hallmarks of actual language. The letter frequencies, word lengths, and repetition patterns mirror those found in natural human communication. Certain characters appear only at the beginnings of words, others only at the ends. The "words" seem to follow consistent grammatical rules.

The manuscript is no casual doodle.

Microscopic analysis shows that someone with the practiced fluidity of the writing system wrote the text without hesitation marks. No revisions. Just the smooth, confident hand of someone writing in what appears to be their native script—a script that exists nowhere else in the historical record.

You don't need to examine the illustrations long to see that the plants don't exist, wired as they are with impossible root structures and leaf arrangements.

For a complete physical description and foliation, including missing leaves, see the Voynich catalog record.

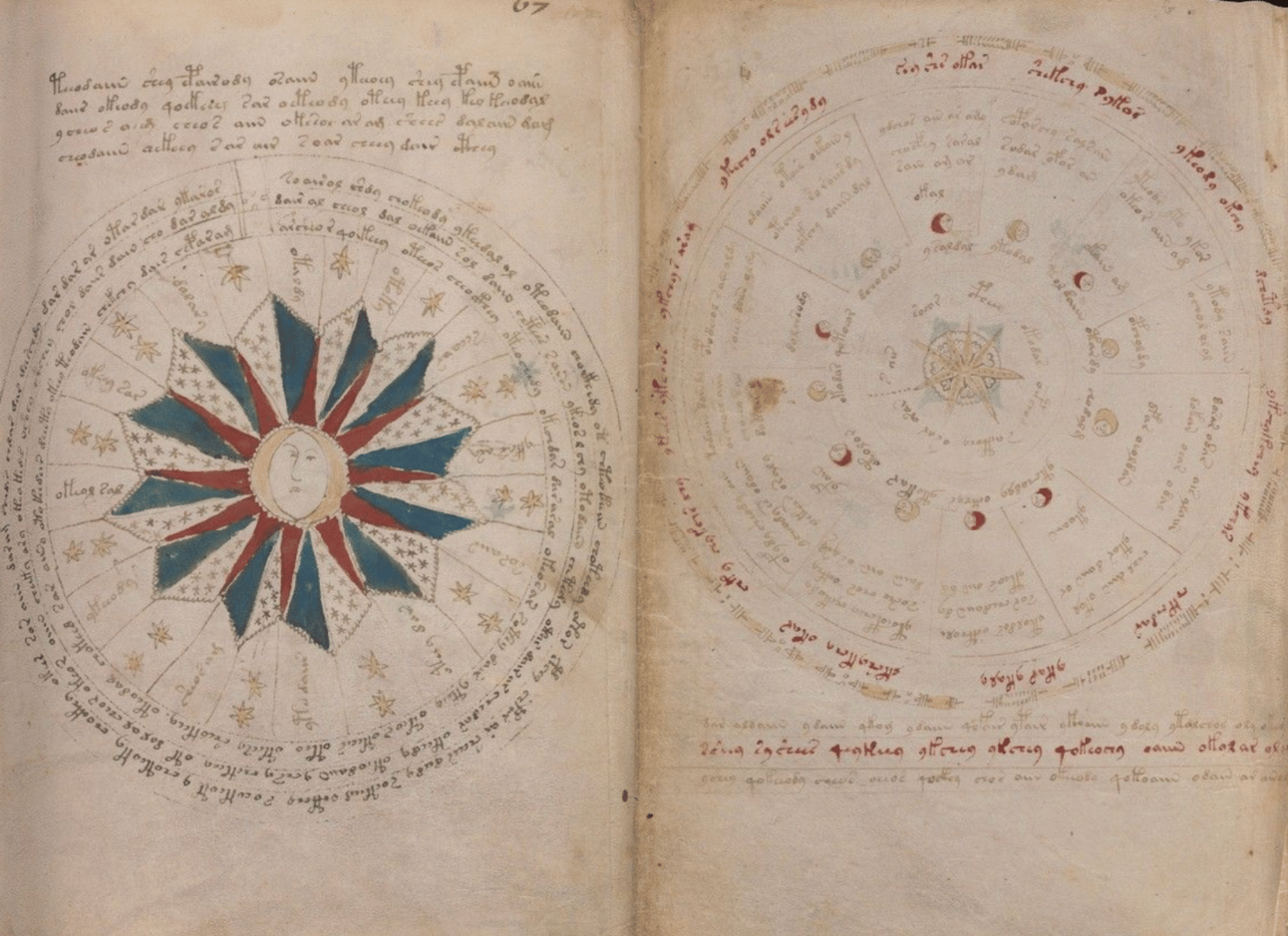

The astronomical pages show circular diagrams with symbols suggesting Zodiac meanings but conforming to no known medieval cosmology.

Most bizarre are the "balneological" pages, showing naked female figures bathing in interconnected pools of greenish liquid, some emerging from what appear to be organic tubes or pods.

All were meticulously drawn in expensive pigments on high-quality calfskin parchment that carbon dating places between 1404 and 1438. Someone invested serious time and resources into creating this object, but why? And to what end?

To read a detailed chemical analysis, go here.

We Be Stumped.

The history of attempts to crack the Voynich code reads like a catalog of brilliant people being utterly humiliated and involves a bunch of Williams (okay, two).

William Friedman led the team that broke Japan's Purple cipher in WWII—an achievement that changed the war's course. Yet, after 30 years of studying the Voynich Manuscript with his equally brilliant wife Elizebeth, he admitted defeat, suggesting only that it might be an early constructed language.

William Romaine Newbold (so many Williams!), a respected medieval scholar, announced with great fanfare in 1921 that he'd discovered Roger Bacon's secret microscopic shorthand in the text. His theory collapsed when another scholar demonstrated that the "microscopic characters" were cracks in the aged ink.

More recently, in 2019, Gerard Cheshire published a paper claiming the manuscript was a Proto-Romance language containing women's health information. Other scholars tore apart his work. The University of Bristol, which had initially promoted his findings, formally withdrew its support. The ruthlessness of Voynich scholars toward failed theories is matched only by their eagerness to propose new ones.

Even modern computational approaches have failed spectacularly.

We've run the manuscript through machine learning algorithms, statistical analyses, and pattern-matching software. We've learned that the text follows Zipf's law—a linguistic principle that states the most common word in any language occurs 2x as often as the second most common word, 3x as often as the third most common word, and so on—with suspicious perfection, yet predates our understanding of this principle by centuries.

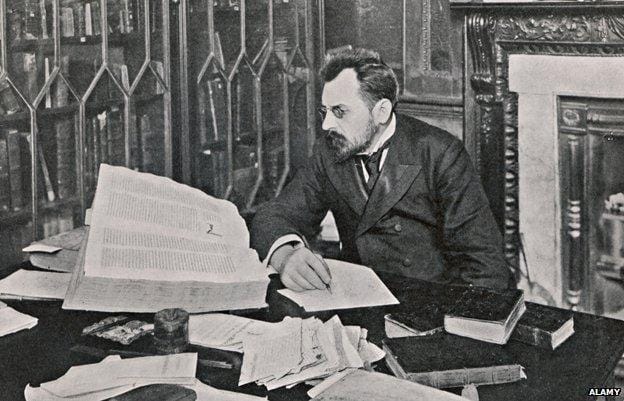

Wilfrid Voynich

Wilfrid Voynich

The manuscript's modern history begins with its namesake, Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish revolutionary turned rare book dealer who claimed to have discovered it in 1912 at a Jesuit college near Rome.

But Voynich was no ordinary antiquarian. Born in Lithuania in 1865, he had been imprisoned in Siberia for revolutionary activities before escaping to London in 1890.

Voynich claimed the manuscript came with a letter dated 1665 stating that it had once belonged to Emperor Rudolf II of Bohemia, who reportedly paid 600 gold ducats for it, believing it to be the work of the 13th-century philosopher Roger Bacon.

After Voynich died in 1930, the manuscript passed to his widow, Ethel Lilian Voynich (herself the daughter of mathematician George Boole). Following her death, someone sold it to rare book dealer Hans P. Kraus, who donated it to Yale University in 1969 when he failed to find a buyer willing to meet his asking price of $160,000.

Throughout this journey, the manuscript remained stubbornly silent, guarding its secrets with the same inscrutability it had shown for centuries.

The Psychology of the Unsolvable

In all this rich history of trying to solve what many consider unsolvable, I wonder: What if it’s been speaking to us the whole time, but our preoccupation with solving its puzzle is preventing us from listening to its clues?

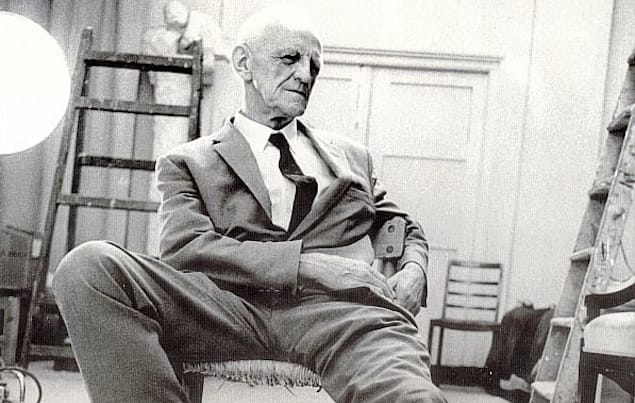

In 1953, pediatrician and psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott introduced a concept that explains our weird relationship with this manuscript. He called it "potential space"—the space between the experiencer and the experience. This area of human awareness is neither purely subjective internal nor objective external reality, but something gloriously in-between—a third space.

D.W. Winnicott

"It is in the space between inner and outer world," Winnicott wrote, "that intimate relationships and creativity occur."

This potential space is where we play, create art, engage with culture, and do our most interesting thinking. It's a mental playground where we're neither lost in pure fantasy nor confined to dry facts.

The Voynich Manuscript lives in this middle space. We’re too busy carbon dating and objectifying its physical properties to be in this middle space. The Voynich Manuscript creates the perfect potential space.

Creative thinking involves activating two opposing brain networks: the default mode network (our internal daydreaming system) and the central executive control network (our external problem-solving system).

Most problems force us to use one or the other. But the Voynich Manuscript activates both networks simultaneously with its tantalizing almost-meaning. It's rewiring our brains as we engage with it, creating neural pathways that strengthen our ability to hold complexity and contradiction.

This explains why some researchers describe working with the manuscript as "exercising the muscle of mystery." It's mental cross-training for a world increasingly divided between those who demand absolute certainty and those who surrender to pure relativism.

And the manuscript offers this middle path: a rigorous engagement with evidence that never collapses into final answers.

The manuscript provides a sanctuary of productive uncertainty in our algorithm-driven world, where answers arrive before we finish typing questions. It teaches us that some mysteries are valuable not despite their resistance to a solution but because of it.

Maintaining engagement with partial understanding may be the most important psychological skill for the 21st century.

Finding Your Own Voynich

Want to cultivate your relationship with productive mystery? Try:

Engaging with art forms that resist immediate interpretation

Asking research questions where partial answers lead to better questions

Developing comfort with provisional rather than absolute knowledge

Recognizing when the pressure for certainty is closing down your creativity

Practicing "epistemic vulnerability"—acknowledging that many of your most essential beliefs remain open to revision

The Manuscript's True Message

What matters isn't deciphering the manuscript's text but recognizing that meaning itself is never extracted but always co-created between text and reader, artifact and observer, world and perceiver.

The Voynich Manuscript doesn't mock our intelligence or celebrate our limitations. It invites us into a relationship with the mystery itself—a particular kind of understanding that remains perpetually generative precisely because it remains incomplete.

In a world that increasingly demands certainty, that's precisely the message we need to hear.

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

Today in psychological history: On March 19, 1788

The first patients were admitted to the new St. Bonifacio Hospital in Florence, Italy. St. Bonifacio was built by the Grand Duke Leopoldo I, whose "leggi sui pazzi" (law on the insane) (1774) was Europe's first statue providing care for people with mental illness. St. Bonifacio's director, Vincenzo Chiarugi, was among the first to institute humane standards of care.

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade