Happy Wednesday, friend!

You are reading The How to Live Newsletter: Your weekly guide offering insights from psychology to help you navigate life’s challenges, one Wednesday at a time.

Donating is Advocating

The How to Live newsletter is a free mental health resource. I spend hundreds of hours and dollars a month to keep it going.

Everyone who helps sustain this project becomes a mental health advocate.

If you’ve gained wisdom or gleaned insight from this newsletter, please consider a donation in any amount, or upgrading for $6/month and help me continue to write this newsletter.

Your patronage has an enormous impact and makes a real difference.

🙏🏼 ❤️

What Looks Like a Crush but Feels Like Obsession? Limerence.

The experimental psychologist Dorothy Tennov writes in her 1979 book Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love, of the moment she began to take an interest in the systematic study of romantic love.

“You think:

I want you.

I want you forever, now, yesterday, and always.

Above all, I want you to want me.

No matter where I am or what I am doing, I am not safe from your spell. At any moment, the image of your face smiling at me, of your voice telling me you care, or of your hand in mine, may suddenly fill my consciousness rudely pushing out all else.”

It was a fall afternoon in the mid-1960s when Dr. Tennov walked into her office from class to discover her student Marilyn Weber waiting for her. Ms. Weber was particularly impressive and bright, but that day, her posture was sloped, and her eyes were time-stamped red, marking hours of crying.

She’d come to apologize for having failed to hand in an assignment and vowed to get it done within a week.

Without detailing her distress, Ms. Weber said she couldn’t pull herself together, that she wasn’t sure why she was behaving the way she was, but wondered aloud whether life was just too hard for her.

Dr. Tennov flashed to a conversation about romantic love she’d had with two graduate students, a few weeks earlier. Both students described the pain of past breakups and how it rendered them utterly useless.

The emotions they expressed were ones Dr. Tennov had experienced, and she wondered if there was a universally shared progression to the stages of romantic love.

As Ms. Weber headed out the door, Dr. Tennov couldn’t help but ask whether her distress had “anything to do with a disappointment with love?”

Indeed, it had.

Dr. Tennov was curious about this distress caused by love that Ms. Weber was experiencing—indeed, her students had been describing something similar. She turned to her textbooks, journals, psychology papers, and other writing on romantic love but found nothing about the agonizing pain of loving another.

What was this state called?

The question gripped her until she decided to conduct the research herself.

Guided by the notion that this particular love-distress was not a pathological state, nor an aspect of neurotic personality (based on the psychological states of students who were known to her), she concluded that the pain from love must be a normal, universal experience.

Her research required her to seek the answers to the following questions:

What caused people to fall in love?

Were some people more likely than others to fall in love?

Could those who were unhappy in love be helped?

From there, she would record the incidence of unhappy love and look for commonalities that induced love-distress.

She created a questionnaire comprising 200 true or false statements about romantic love, sex, and personal relationships. She solicited volunteers through ads, bulletin boards, newsletters, and in person. She interviewed over 500 people.

Yet, during a conversation about unrequited love, she realized she was closing in on the answer. Those who did not reciprocate love, who didn’t feel the same intensity of feeling, who weren’t gripped by agonizing ruminations about another, were the ones who helped her crystallize the state she was seeking to name.

The term “love” wasn’t quite right. Love doesn’t stay propped in such a heightened state as reported by those trapped inside unrequited longing.

Being in love also didn’t suffice, as the condition described included feelings one had sometimes to endure.

The state being described repeatedly was of an unrequited and agonizing longing for another, a yearning that seeks reciprocity above all else.

This is the state that Tennov coined “Limerence.”

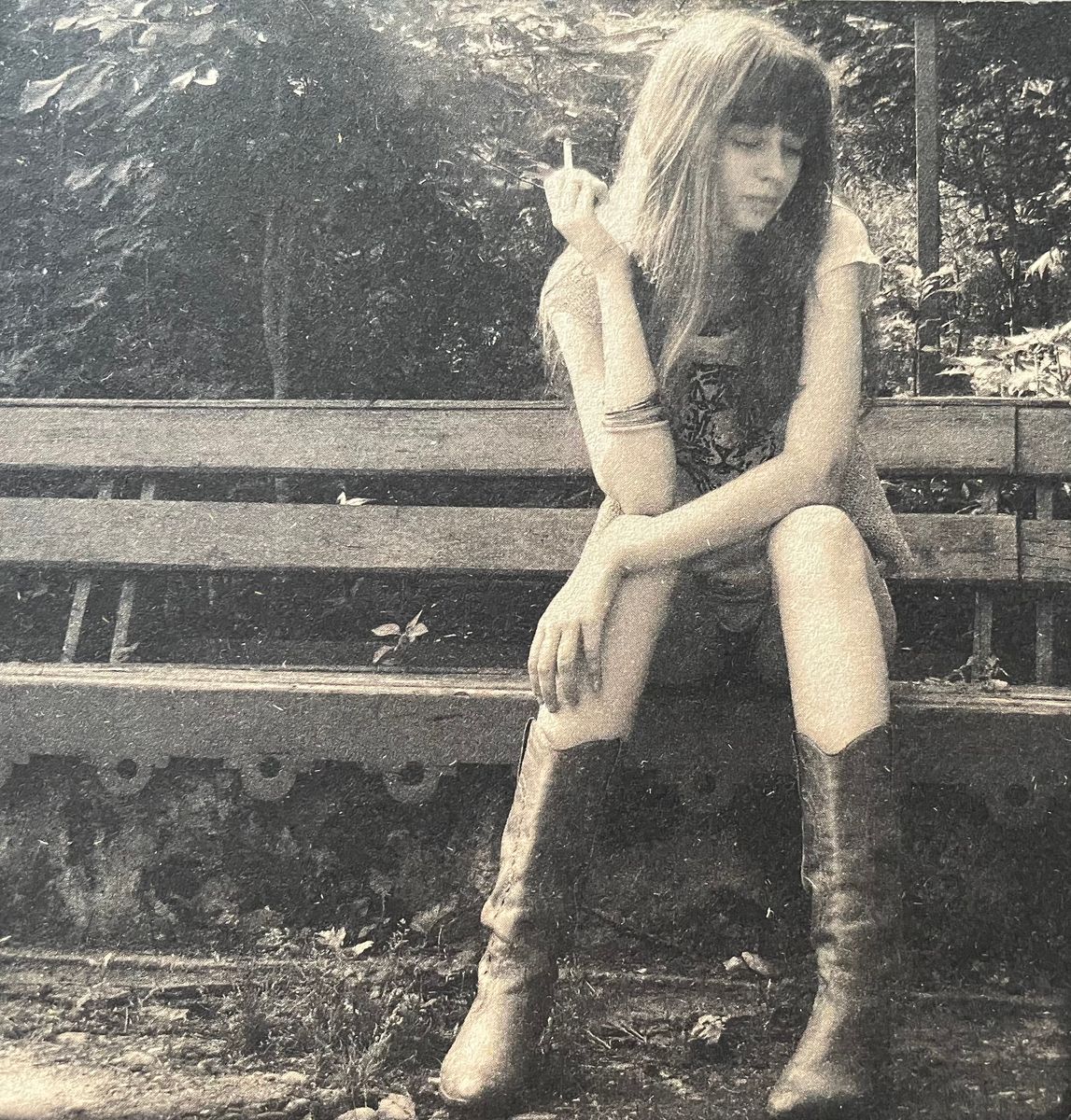

Ivana Helsinki "Lonelytiger" postcard collection, 2009

WHAT IS LIMERENCE?

In her book Love and Limerence, Tennov expressed the difficulty of conveying the specific craving a limerent has for their limerent object (LO) for full emotional enmeshment with another human being, she writes:

My most profound insights don't go in the free version—they're distilled from my 27 years in therapy, decades of independent study, and work as a mental health advocate. These frameworks and perspectives are reserved for readers committed to going deeper.

Join How to Live

Transformative concepts from a lifetime in therapy.

Get Immediate AccessA subscription gets you:

- All articles the moment they're published

- Instant access to the entire archive of 150+ posts

- Occasional bonus posts

- Invitations to seasonal in-person events

- Direct email access: get personalized resource recommendations + advice (ANNUAL PLAN ONLY)

- 15% off all workshops