All in Your Head: Franz Gall, the Fowler Brothers, and the Science That Wasn’t.

I look upon Phrenology as the guide to philosophy and the handmaid of Christianity. Whoever disseminates true Phrenology is a public benefactor.

I believe a central question lurks in the depths of every person, and our lives unfold in pursuit of the answer. For some, the question surfaces fully articulated; for others, it remains mumbled, tangled in the soft algae of their subconscious.

In the 18th Century, a young German boy named Franz Gall seemed born in possession of a question that began in childhood and ended only in death: Why are people different from one another?

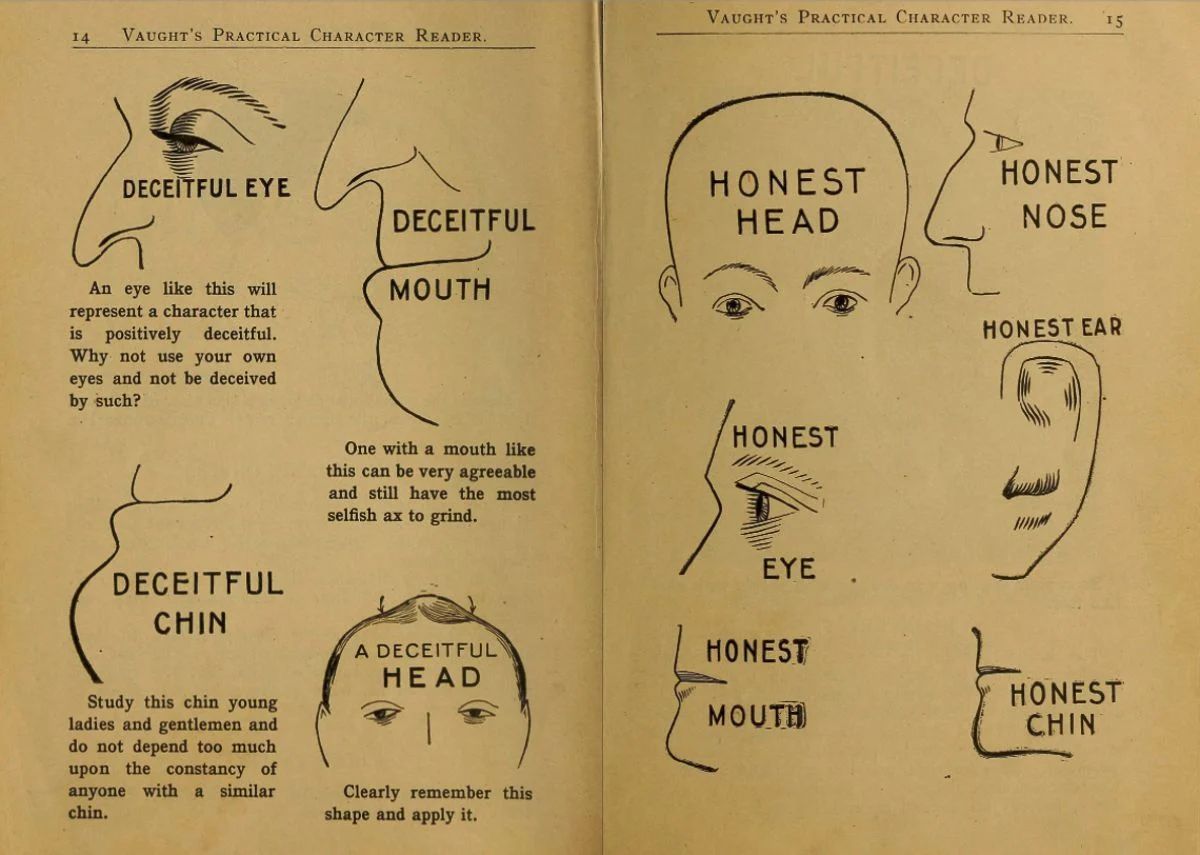

He began from the outside, studying the externals: his siblings’ features, the people in his town, and his parents.

Soon, peculiarities began to stand out. His classmates, for instance, had large foreheads, while others had small ones. He started looking for commonalities. The boys with more pronounced features seemed preternaturally good at memorization, while those with strangely shaped skulls struck Gall as linguistically gifted.

Coincidence? He didn’t think so.

Gall believed there was a connection between the shape of a skull and the capacity of the mind it held.

Born into a world of rudimentary biological knowledge, Gall’s thinking and tools were aligned with the early science of the time, based on description and observation, not experiments.

In 18th-century Europe, the idea that the external form reflected inner reality was not a shallow conceit or unusual.

Gall’s fascination with skulls, anatomy and the nervous system led him to medical school, where he studied under the french physician and naturalist Johann Hermann and Austrian physician Maximilian Stoll whose detailed and systematic approach to his patients history and symptoms left a lasting imprint that natural observation was, above all else, the essential ingredient of science.

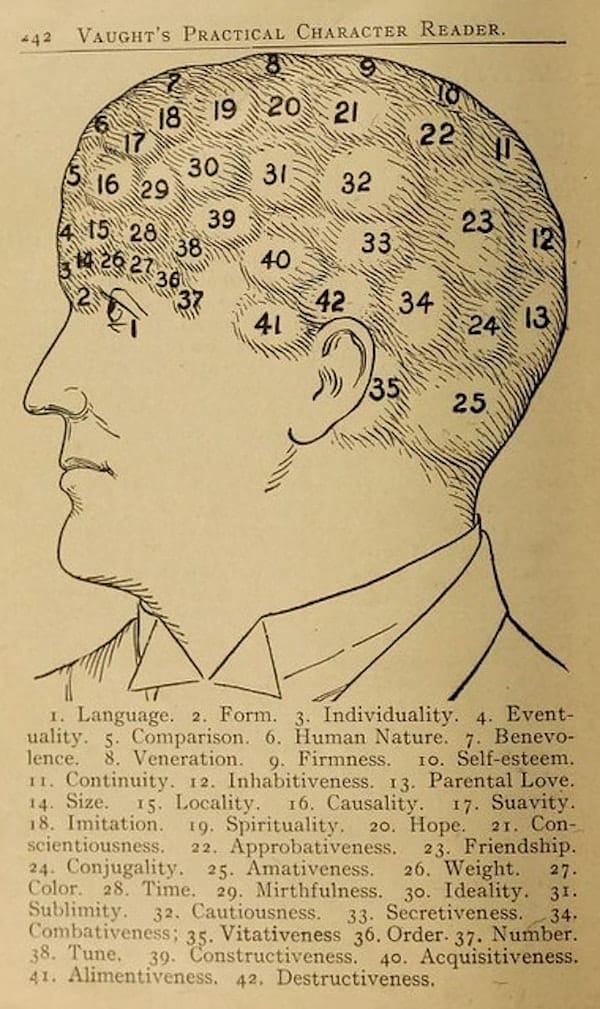

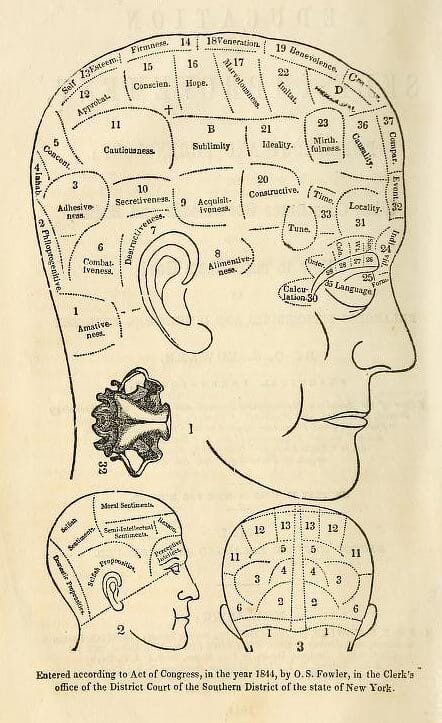

It was there, in medical school, that Gall studied the brains of dissected animals and the details of a human skull—the bumps, ridges, and cavities uniquely different from skull to skull—that he slowly began forming what would become his lasting legacy: Organology AKA Schädellehre (doctrine of the skull).

Rolls off the tongue!

And what if—here’s where Gall’s revolutionary idea emerged—the bumps and ridges of a person’s skull provided a map to an individual’s psychological landscape, characteristics, personality traits, and more?

He divided the brain into 27 distinct sections, ranging from mechanical ability to love of property, from a talent for poetry to what he chillingly termed the “tendency to murder.”

He believed that larger brain areas exerted pressure on the skull, causing bumps on the head. In short, you could read a person’s head and make educated assumptions about their faculties and, therefore, their character. It was a simple, seductive idea—and one that caught fire.

Can’t you smell the eugenics?

Gall’s idea of localization (while heavily influenced by his professors and readings) made Gall the first person to create a theory of mental illness as a brain disease.

The implications of Gall’s claims were staggering: the skull was a blueprint to the human mind, accessible through tactile observation.

It was both a science and a promise—a way to understand ourselves and others without the messy uncertainties of the mind. Gall’s theory spread rapidly throughout Europe and was embraced by scientists and the public. And yet, as seductive as phrenology was, its scientific rigor was shaky at best, and its subtext deplorable.

The heart of phrenology (a term originating from the British naturalist Thomas Ignatius Maria Forster in 1815, and wasn’t used in Gall’s lifetime) and other grand ideas was not destined to remain in circles of privilege.

As H.H. “Henry” Goddard did with Alfred Binet’s first IQ Test, two upstate brothers did to Gall, transforming a science practiced in elite circles into a widespread phenomenon.

Orson Squire Fowler and Lorenzo Niles Fowler came from a modest farming upstate family but, like Gall, were fascinated by unlocking human potential through skull readings.

The brothers discovered phrenology at Amherst College and quickly became its most fervent evangelists. Who wouldn’t be drawn to a science that offered a roadmap to understanding oneself and others, and a tool for self-improvement and social advancement?

The Fowlers saw in phrenology not just a scientific theory, but a business opportunity, and the timing was excellent.

In mid-19th-century America, the country underwent the Second Great Awakening, a religious revival and social reform period. Phrenology fit neatly into this landscape, offering a scientific-sounding method of self-improvement.

The Fowler brothers lectured and “read heads” throughout New England. In 1828, they opened an office called the Phrenological Museum, where they published the American Phrenological Journal.

In 1842, it was off to New York City, now a full-throated family business. The brothers, their sister Charlotte, and Lorenzo’s wife Lydia became notable phrenologists, offering readings to an eager public. Their Phrenological Cabinet, which showcased models of skulls, actual skulls, charts, and other movement artifacts, became a popular fixture in the city.

(We’re talking about actual skulls. Thousands of skulls.)

Fowler and Wells family papers, Division of Rare Book and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Their monthly journal, The American Phrenological Journal and Miscellany, became a best-seller, promoting phrenology and a wide range of reform movements, from temperance to women’s rights.

Not long after, they launched Fowler & Wells, a publishing imprint, producing hundreds of titles, editions, and thousands of copies of phrenological texts. They also sold charts, sets of cranial casts, and the famous symbolic heads.

In addition to their mercantile ventures, the Fowlers were educators, training an army of phrenologists and supplying them with the tools of their trade.

1861

CLASS LECTURES.

The first Course of Instructions in Practical Phrenology, Physiology, and Physiognomy, will commence on Thursday Evening, Dec. 27th, at 7 1-2 o'clock, continuing on successive Thursday Evenings at the Phrenological Rooms, 142 Washington Street.

We shall teach both the Science and the Art of Practical Phrenology, in the most tangible manner possible; bringing to our aid an extensive cabinet of Casts, Skulls, and Paintings. No other subject combines profit and pleasure to such an extent, furnishing to all classes the means of self-improvement and success, and of forming reliable estimates of friends and strangers. To young men and women, and to parents, it is especially valuable.

Butler & Martin, 142 Washington Street, Boston.

It wasn’t just the general public that embraced phrenology. Some of the most notable figures of the time became its adherents. Walt Whitman, “America’s poet” (and my late neighbor in Clinton Hill / Fort Greene, Brooklyn) was a most enthusiastic believer.

The educational reformer, Horace Mann, incorporated phrenology into his vision for American schools.

Even Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, credited phrenology with giving her the confidence to pursue her humanitarian work.

Mark Twain famously underwent a phrenological examination (in fact, he kept returning, testing the accuracy), and he was unimpressed, resentful, and also hurt. Not just by Fowler’s indifference to him, but by the declaration that our most beloved humorist lacked humor!

The phrenologist found a cavity in my head that he said represented humor.

But phrenology had a dark side that paved the way to Scientific Racism. Phrenology gave birth to the Eugenic IQ testing movement, skull-measuring, and an array of malignant taxonomies and classifications relegating Caucasians to the highest form of human.

And while its rise was meteoric, its fall came just as swiftly. Marie-Jean Pierre Flourens, a French physiologist, conducted experiments in the early 19th century that debunked Gall’s theory.

By removing parts of animals’ brains, Flourens demonstrated that mental faculties were not confined to specific areas. Instead, the brain worked as an interconnected whole.

Flourens’ work laid the foundation for our modern understanding of brain plasticity, and as science advanced, phrenology’s appeal began to fade.

As neuroscience blossomed, Gall’s once-radical theory was relegated to the dustbin of pseudoscience. The Fowler brothers saw their empire crumble. Orson turned to promoting octagonal houses as ideal living spaces, while Lorenzo continued practicing phrenology but to ever-diminishing returns.

Phrenology is now viewed as little more than pseudoscience reeking with an acrid stench of eugenics, but its legacy endures in subtle ways. Modern neuroscience has confirmed that certain brain areas are specialized for specific tasks, though far more complex than Gall ever imagined.

More enduring, perhaps, is phrenology’s lesson in the allure of simple, compelling narratives. It offered a tantalizing explanation for human nature, wrapping the mysteries of the mind in an easily digestible, almost physical form.

Gall’s quest was not without value. He asked bold questions, pursued them rigorously, and built a theory that, while flawed and often creepy, captured the imagination of his time.

Ultimately, phrenology was less about the bumps on our heads and more about our enduring need to understand ourselves. In this, Gall was not so different from the rest of us, quietly pursuing the central question of his life: Why are we different from one another?

Even if we never find the answer, the question of self is always worth pursuing.

What’s your take on phrenology? Leave your thoughts in the comments!

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade