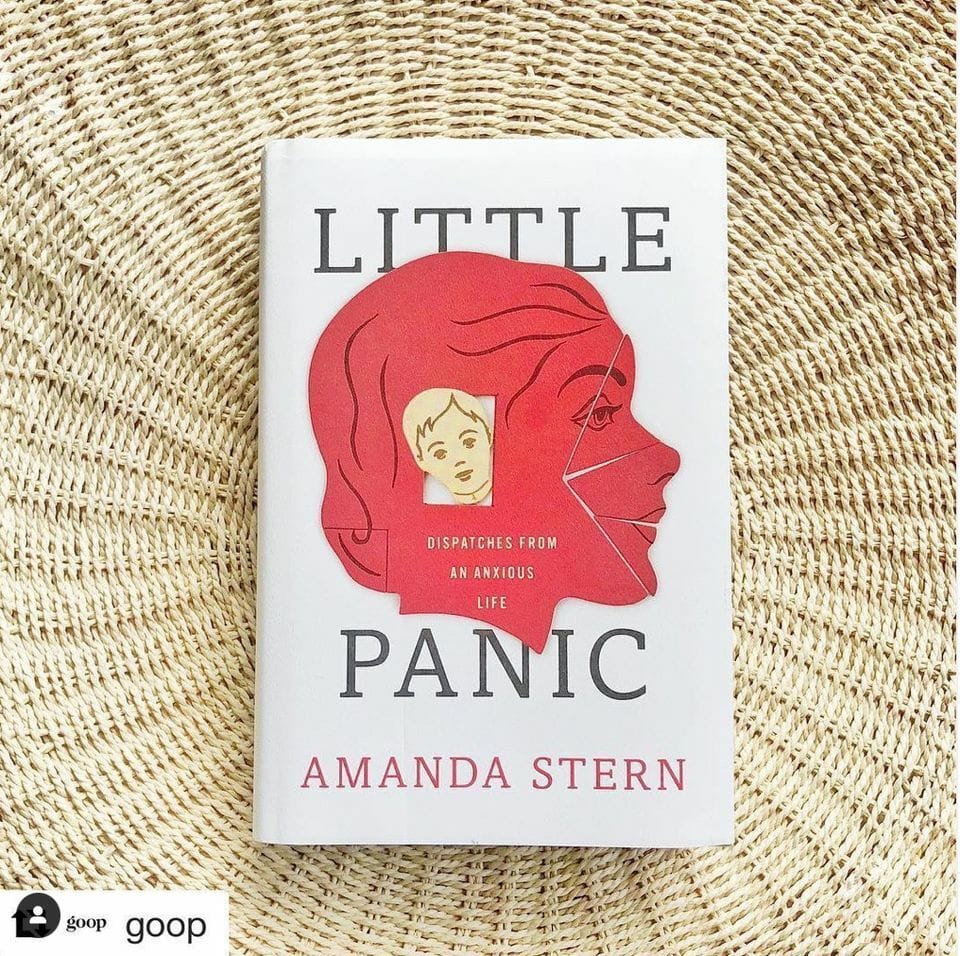

In 2018, I published a memoir called Little Panic: Dispatches from an Anxious Life about growing up in Greenwich Village in the 1970s and ’80s with an undiagnosed panic disorder, and how recognizing something was wrong with me without knowing its name until I was 25 years old, shaped the course of my life.

The book did much better than I anticipated any book of mine ever would.

GOOP chose it for their book club, O Magazine selected it as one of the best summer books, People Magazine featured it, and Publishers Weekly gave it one of its coveted stars.

All those things were amazing—I was floored.

But those moments, thrilling as they were, did not define the book’s success for me. In my eyes, the mark of its success was the flow of invitations over the past four years from schools across the country to speak to hundreds of students, parents, teachers, and community members, ranging in age from 5 to 95.

I tailored my talks to the specific community I was in, but the content of the talks—a distillation and simplification of my book, including my story, many of my thoughts on how we raise, consider, treat, and experience kids; the flawed model of child-rearing many adults default to—remained at the core.

Since the pandemic, I’ve only given a handful of talks, all on Zoom, and I miss the in-person engagement, the swarm of students afterwards wanting to confess and confide, and the absolute pure love I feel in those moments for these incredible children who want to be seen, heard, understood, and loved. Same as we all do.

So, for today’s post, I offer the greatest hits, the best bits, from the central talk that I deliver to high-school students.

This is a highly condensed version-it doesn't go into detail about my childhood or my panic disorder (for that, you'll have to read the book)-but I still hope you get something out of it.

THE (HIGHLY-CONDENSED) TALK:

"I believe that it’s our moral responsibility to share our personal experience of being human. Without sharing that information, we are left to wonder whether we’re doing life wrong, and we walk around with the secret worry that we’re defective and broken.

So, this is me sharing with you my experience of being a human being on this planet so that you can know that you’re not weird, wrong, broken, or alone. So that you can understand that feeling, wrong and broken is the most human feeling of all.

I grew up in Greenwich Village with an undiagnosed panic disorder and had no idea what was wrong with me until I was 25. I want to tell you the story of how my very well-meaning parents, teachers, doctors, and other adults in my life overlooked and ignored my anxiety, and the way that led me to feel defective and devalue,d and made me feel like I needed to hide my true self from the world.

But before I do that, I want to take a second to talk about the difference between typical anxiety and disordered anxiety.

Typical anxiety occurs in response to a stressor, like an exam, a fight with a friend, or your parents. It doesn't feel good, but it passes.

Typical anxiety is fleeting.

Disordered anxiety is not fleeting.

It is relentless, clingy, and will not leave you alone. It interferes with your entire life. Typical anxiety is your stable, grounded, well-adjusted friend. Disordered anxiety is that toxic person in your life you cannot shake, no matter what.

I’ve had toxic-person anxiety my entire life.

My first memory, when I was around 3, is of having a panic attack.

As a child, I was convinced my mom would die or disappear if I wasn’t watching her. I believed that after I left for school every morning or for my dad’s house every other weekend, she’d forget she had kids and move to Europe without telling us.

I refused to sleep at friends’ houses and never let anyone sleep at mine.

I was worried they would distract me from keeping track of my mom’s whereabouts. At night, I’d watch out my window to ensure my mother wasn’t running away to join another family.

No matter how much I begged, I had to leave for school every morning and my dad’s every other weekend.

To me, separation meant death.

My worries were so extreme that they interfered with absolutely everything I did. I felt my fears, both inside my body and within my body. I don’t think I took a full breath until I was 25.

Deep down, I believed that something was horribly wrong with me, that I had some defect no one else had. And because no one else had it, that meant I was broken, and this was a fact I needed to hide from the world.

Original art for How to Live by Edwina White

The closer it got to leaving my mom, the worse I felt. I acutely sensed time passing, of the closing gap between present and future, like an invisible force dragging me by my ankles toward quicksand, eager to drown me out—dead.

And, on the day I had to part with my mom, I’d feel myself turning into a balloon, floating up to the ceiling where I’d observe myself in the third person below, like I was watching myself in a movie. I began to think that I was crazy, and I was only 7.

Things only got worse from there.

My most profound and personal insights don't go in the free version—they're distilled from my 27 years in therapy, decades of independent study, and work as a mental health advocate. These deeper dives are reserved for readers committed to going deeper.

Join How to Live

Transformative concepts from a lifetime in therapy.

Get Immediate AccessA subscription gets you:

- All articles the moment they're published

- Instant access to the entire archive of 150+ posts

- Occasional bonus posts

- Invitations to seasonal in-person events

- Direct email access: get personalized resource recommendations + advice (ANNUAL PLAN ONLY)

- 15% off all workshops