This newsletter is free for students under 26 with a valid .edu email, and for anyone who could benefit from these resources but for whom $6/month isn’t feasible. If that’s you, email me and I’ll set you up with a free subscription. You’re welcome here—no explanation required.

Give Me the Doll That Looks Nice

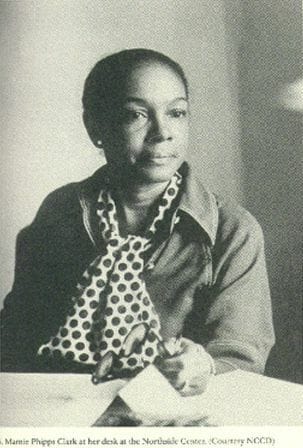

Today, I’m bringing you a story about the first black woman to get a Ph.D. from Columbia; a formidable psychologist, responsible for a landmark study that helped end school segregation, yet it was her husband who got most of the credit.

We're talking about Mamie Phipps Clark.

In high school, I remember learning about Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896)—the Supreme Court case which declared that racial segregation was constitutional so long as facilities were of equal quality, a concept known as “separate but equal”—though at the time, I was unable to make sense of the cognitive dissonance required to comprehend such a framework.

The Supreme Court revisited this case, most notably in 1954 with Brown v. the Board of Education, which ruled that racial segregation of children in public schools was, in fact, unconstitutional, declaring that “separate but equal” was as dissonant as it sounded.

What eluded the whole discussion was the significant role social psychologist Mamie Phipps Clark had in the decision.

Phipps Clark, the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1943, devoted her work to assessing the racial consciousness and self-consciousness of Black children in segregated education.

Born in the Jim Crow South in 1917 in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to a well-respected physician and a homemaker, Phipps experienced firsthand what it was like to have few rights and be barred from most public establishments. Black people couldn’t vote and were denied the right to an equal education—with the resources allotted to white students.

As a child, Phipps would have to mentally gear up in protective armor every time she walked to and from school. The Black kids had to pass the white kids on the street because the Black school was on one side of town, the white school was on the other, and the white kids would often pick fights with them.

When Phipps was about 6 years old, there was a lynching in her town. There was only one road in town, and she remembers seeing people running and shouting that a mob was coming into the city. A white mob had pulled a Black man out of the local jail and brought him into Hot Springs, dragging him up and down the main street before taking him outside the city to lynch him.

She never witnessed any of it but remembers, “It was a very chilling thing. I’ll never forget it, because people were describing it—whether they had seen it or not, I don't know—but there were very vivid descriptions of it. It was a very awful thing, and for days we were afraid almost to go out of our house.”

It wasn’t until she pursued her doctorate at Columbia University in New York City that Mamie Phipps attended an integrated school.

Paying It Forward

Every paid subscription helps fund free memberships for students and people who need access but can’t afford it right now.

If you believe in this work and want to support a more humane, accessible mental health conversation, I’d be grateful if you’d consider upgrading.

Segregation cast an indelible impact on her childhood. So much so that she would eventually decide to base her studies on the harm segregated education has on Black children.

A serious academic ever since childhood, Phipps was attuned since doing her undergraduate work in mathematics at Howard University to the lack of support women got, especially in fields dominated by men—and in particular, white men. That she was one of few women studying math made it that much harder. It was a dispiriting time for her, but Phipps was buoyed when she met Kenneth Clark, a graduate student getting his master's in psychology.

Clark saw firsthand how poorly Phipps’s professors treated her, and he encouraged her to switch concentrations from math to psychology. As she considered it, she realized that she’d always been interested in the field, abnormal psychology specifically, as the subject would allow her to work with children, a lifelong dream.

She switched concentrations. In her senior year of college, she and Kenneth Clark eloped.

Mamie Phipps Clark and Kenneth Clark Columbia University

The summer after she graduated from Howard, in 1936, Phipps landed a job in the law office of NAACP attorney Charles Houston. It was there that Mamie watched as Thurgood Marshall, among others, worked tirelessly, vigorously preparing cases that would legally challenge racial segregation across the country.

Seeing this concrete action to desegregate schools firsthand gave her hope—and a mission.

THE DOLL TEST / MASTER’S THESIS

That fall, Mamie Phipps Clark returned to Howard to pursue her master’s in psychology, where she was focused specifically on pinpointing when Black children become conscious and aware of their race.

Her research for her thesis, “First Interests in Children and development of Consciousness of Self,” led Mamie to discover that Black children in segregated public schools become aware of their race very early, which led her to wonder whether segregation impacted their self-esteem and personal development.

If so, did it play on unconscious or conscious racial preferences?

These questions spurred her husband’s interest in her research and served as the foundation upon which they’d later collaborate, testing on a much broader scale racial preferences of Black children, whose results would ultimately change the world. Kenneth Clark was quick to say that “this was Mamie’s primary project that [he] crashed.”

Mamie Phipps Clark and Kenneth Clark The Decision Lab

Together, Mamie and Kenneth recruited children and presented them with pictures: of white boys, Black boys, and innocuous images of animals and random objects. They asked the boys which picture looked like them and then asked the girls which picture looked like their brother or other male relatives.

The study revealed racial awareness in Black boys as young as age 3. Their responses to the images and objects led to the Clarks’ conclusion that awareness of self as Black led to a sense of inferiority and self-hatred, results that Kenneth found disturbing.

Between 1939 and 1940, the Clarks published three major articles featuring Mamie’s thesis work and published their conclusions.

In 1940, Mamie Phipps Clark enrolled at Columbia—she was only the second Black person in the department. The first was her husband. She wanted to study with famed scientific racist and eugenics, Henry Garrett, specifically to challenge his factually incorrect theories about white superiority. (She was a serious badass.)

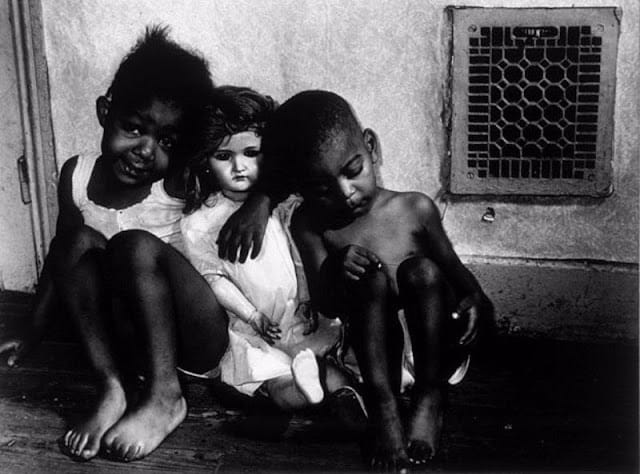

Mamie Phipps Clark and some of the children from the study Cassius Life

The couple applied for the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, a program to support, fund, and advance the careers and achievements of Black people. They were eager to prove that awareness of racial difference hurt Black children and interfered with their development, proving that Black people were not innately or biologically inferior but were barred from success by society. They were awarded the fellowship in 1940 and again in 1941 and 1942.

Their proposal included the tests they’d already done and added a coloring test and a doll test.

In 1943, Mamie Clark was not only the first Black woman to graduate from Columbia with a Ph.D., but she studied, collaborated, and won fellowships while raising two children.

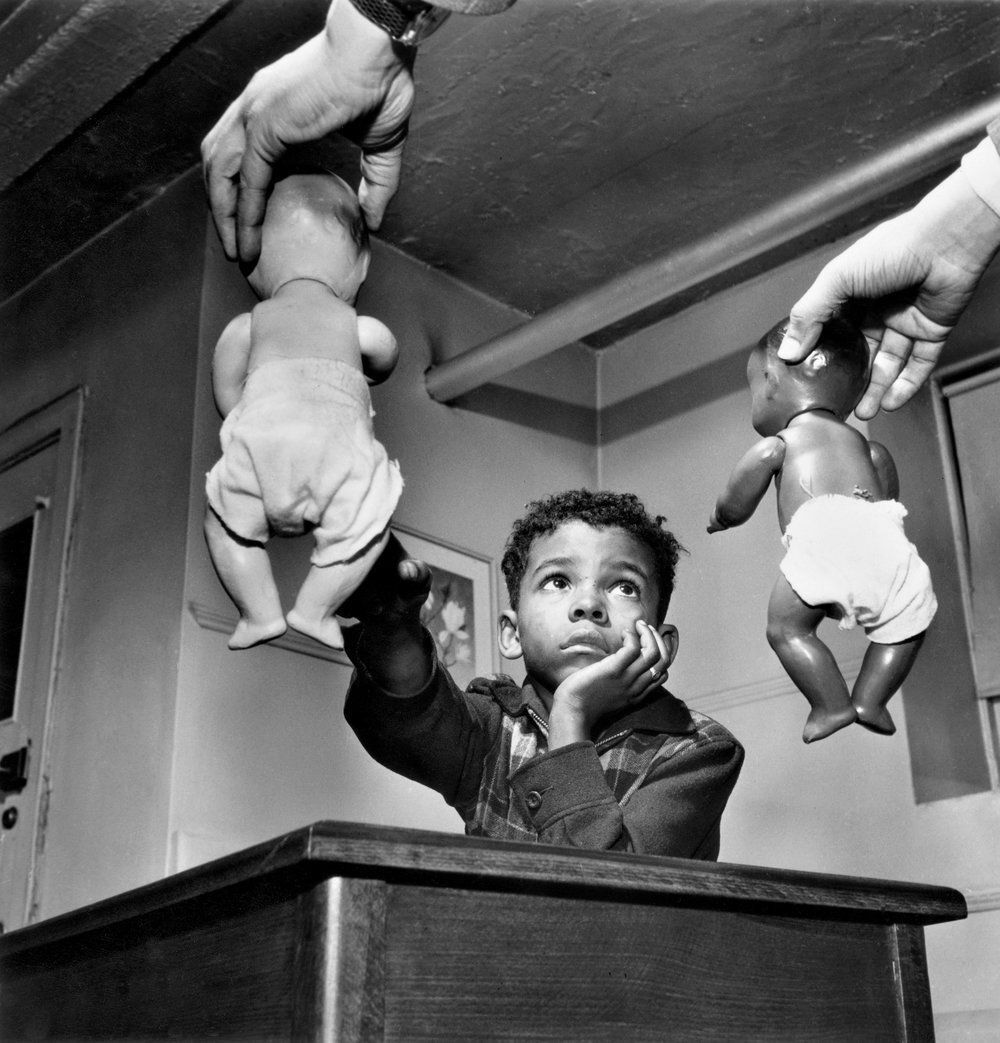

“The Doll Test,” which Mamie conceived, would change history. The study was conducted in Arkansas and Massachusetts.

She and her husband met 253 African-American children between the ages of 3 and 7. The 134 children they interacted with in Arkansas went to segregated nursery schools. All 119 children in Massachusetts attended integrated schools.

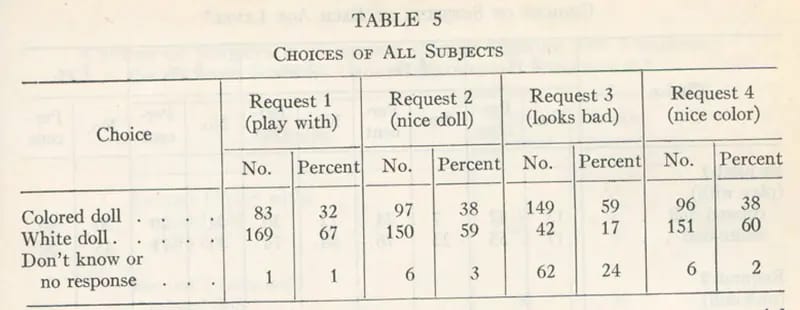

THE CLARKS’ DOLL TEST: 1943

A Black child sits in a room with four dolls on the table (only black children were included in the doll study). Two of the dolls have brown skin and black hair. Two of the dolls have white skin and yellow hair. The psychologist sits at the table with the child and then asks the child a series of instructions and questions.

Give me the doll that you like to play with.

Give me the doll that is a nice doll.

Give me the doll that looks bad.

Give me the doll that is a nice color.

Give me the doll that looks like a white child.

Give me the doll that looks like a colored child.

Give me the doll that looks like a Negro child.

Give me the doll that looks like you.

The child’s responses are recorded, the experiment ends, and the responses are tallied.

The Clarks’ Doll Test study surprised everyone. The responses from the Southern and Northern school children were similar.

67% of the Black schoolchildren indicated that they preferred playing with the white doll, 59% thought that the white doll was “nice,” and only 17% thought that the white doll looks bad.

As many as 59% of the Black children indicated that the brown doll “looks bad.”

Everyone found the response to the last question the most upsetting.

“Give me the doll that looks like you.”

At this question, the Clarks reported that some children “broke down and cried.” Two stormed out of the testing room, “unconsolable, convulsed in tears.” As Kenneth recalled.

He and his wife concluded that “color in a racist society was an alarming and traumatic component of an individual’s sense of his own self-esteem and worth.”

This gut kick of a response is not just history. The test was given again in 2010 to white and Black children, and they, too, broke down in tears when they had to choose a doll that looked like them. That study also showed a bias toward lighter skin.

Mamie Phipps Clark drawn by Edwina White

"These children saw themselves as inferior and accepted the inferiority as part of reality," said Kenneth Clark said.

For the drawing portion of the study, the Black children drew themselves as white. They explained that they didn’t want to be black, so they portrayed themselves the way they wanted to be seen.

The Clarks realized from their studies that segregation made Black children feel inferior. Being separated from white children led to self-hatred that began as early as 3. They understood that the longer these Black children were segregated, the worse off they’d become.

The Clarks wanted to take what they learned from the study and make a difference, so in 1946, they opened the Northside Center for Child Development in Harlem (which is still open today).

This would be the only organization in the city to provide mental health services to Black children.

They also offered social and psychiatric services, psychological testing, and academic services.

BROWN V BOARD of EDUCATION

In 1951, Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, after his daughter Linda Brown was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary school.

In his lawsuit, Brown claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to white schools and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment, which says that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The case went before the U.S. District Court in Kansas. While it agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children” and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” it upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine.

But in 1954, a group of Black parents filed a class-action suit stating that the educational facilities for Black children were not equal. Thurgood Marshall (the head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Educational Fund, who, in ten years, would become the first Black Supreme Court Justice) was their lead attorney.

It was during this case that the doll experiment played a vital role.

Marshall, who knew the Clarks, enlisted the help of Kenneth Clark to join his staff and help find other expert witnesses to testify on the social and psychological damage of racial segregation. (Note: they did not ask Mamie Clark, who conceived of the study, to join their staff, just her husband.)

They asked Kenneth Clark to conduct the doll test again, which yielded the same results: The Black children saw themselves as inferior to the white children. Thurgood Marshall used the Clarks’ Doll Study and the couple’s published articles to bolster the claim that the separate-but-equal doctrine damages Black children, a clear violation of equal protection under the 14th Amendment.

In one of life’s rare moments for comeuppance, Dr. Mamie Clark was called to the stand to refute the testimony of her racist Columbia professor Henry E. Garrett, who held fierce to his convictions that Black children were inferior to white children.

And in 1954, Thurgood Marshall was victorious as the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

There is no question that Mamie Phipps Clark's Doll Test greatly influenced the decision.

In 1973, Dr. Mamie Clark was awarded the American Association of University Women achievement award for “admirable service to the field of mental health.”

Ten years later, the National Coalition of 100 Black Women awarded her the Candace Award for humanitarianism.

Mamie Clark died in 1983 from lung cancer. But her legacy, from inciting an entire psychological field devoted to race studies to her work that helped dismantle school segregation and create equality in the world, lives on.

Dr. Mamie Phipps Clark's steadfast belief in equality is an inspiration.

The Original Doll Study (this is a pdf download).

Until next week I remain,

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade