You’re reading How to Live—an inquiry into the psychological forces that shape us, and how to stop being run by them.

Through deep research, personal storytelling, and hard-won insight, I challenge the myth of normalcy and offer new ways to face old struggles.

This work is reader-supported. If it speaks to you, consider a paid subscription for deeper insight, off-the-record writing, and seasonal in-person gatherings.

You can also donate any amount.

The Truth About Going Mad in America

In 1973, when Jonathan Rosen was ten years old, his family moved to New Rochelle, New York. The son of intellectuals–a novelist mother whose best friend was Cynthia Ozick, and a professor father who escaped the Holocaust on the Kindertransport as a child–Jonathan was raised with Jewish ideals valuing intellectual excellence.

Named after his grandfather, who was murdered in the Holocaust, Rosen wore an anxious sadness, but was sustained by the belief that he could do great things.

Down the street lived another 10-year-old boy from a family of Jewish intellectuals named Michael Laudor. Charismatic and funny, Laudor devoured multiple books a week, which he retained with his photographic memory. He dazzled adults and peers alike with his effortless aptitude and preternatural confidence—by all accounts, he was a genius.

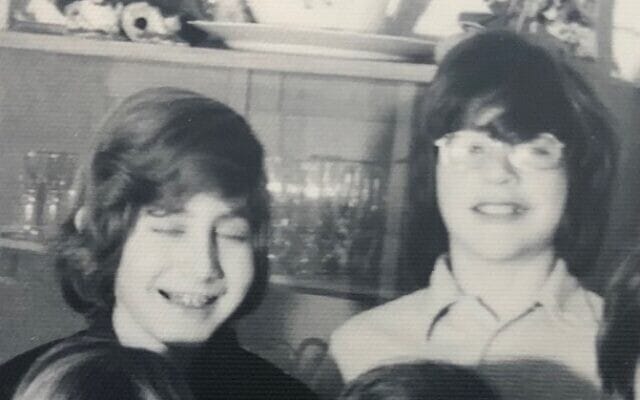

Jonathan Rosen (left) and Michael Laudor (right)

Rosen and Laudor's symbiotic intellectual curiosity sparked an intense friendship. Their conversations were fueled by big ideas and grand visions, bonding them instantly, setting them on parallel paths which found them at the same sleepaway camp, the same prestigious summer program, sharing dreams of becoming writers, and vying for the same positions and accolades, easily meeting the expectations for greatness they’d grown up with, until their lives suddenly and dramatically diverged in ways no one saw coming.

Both were accepted into the Telluride Association Summer Seminar in high school, an immersive educational experience held at Cornell University for exceptional students, and then to Yale, marking their inevitable entrance into the world of the white, male American meritocratic elite.

However, while the anxious Rosen often walked in the shadow of Laudor's genius, he ultimately escaped the tragic consequences of being struck down by mental illness, a crisis that claimed Laudor in his 20s, violently derailing his trajectory and ending the life of his pregnant fiancée, Caroline “Carrie” Costello.

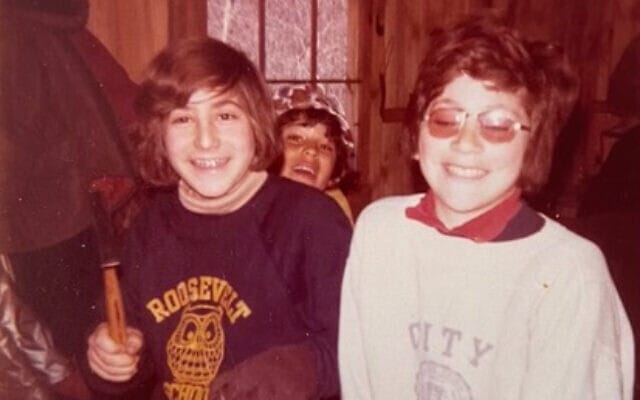

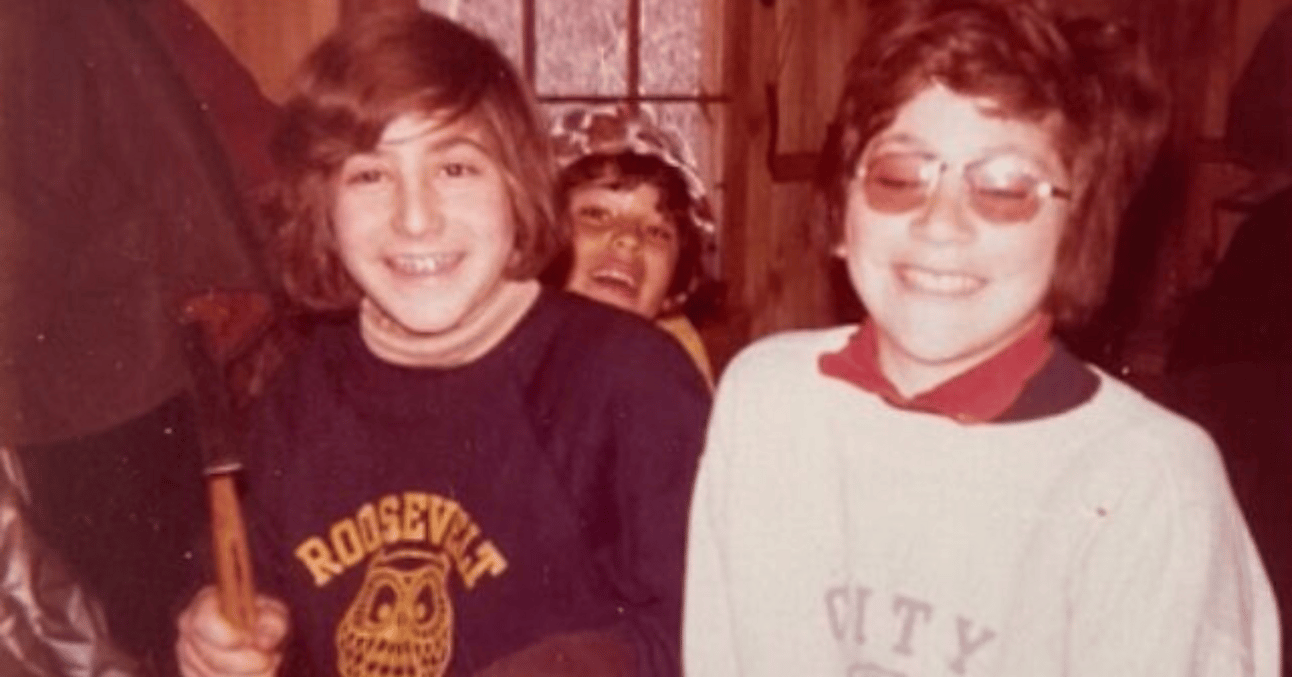

Jonathan Rosen (left) and Michael Laudor (right)

In his memoir The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions, one of the New York Times’ 10 best books of 2023 (and a Pulitzer Prize finalist!) Rosen writes about this friendship, his younger anxious self who envied his friend’s genius, and the divergent trajectory of their lives as Laudor was ravaged by psychosis due to Shizoaffective disorder—a mental health disorder marked by hallucinations, delusions, depression and mania, which ultimately claimed three promising lives.

This is the story of Michael Laudor, Carrie Costello, and the perils of going mad in America…

The brilliant Laudor breezed through Yale in just three years graduating summa cum laude—"Summa Cum Laudor," as Rosen joked—with a double major.

After college, Laudor accepted a high-pressure job at the consulting firm Bain & Company, where he began exhibiting paranoid delusions, believing his phone was tapped. As job stress exceeded his ability to cope, his paranoia escalated drastically: he was convinced Nazis killed and replaced his parents, his bandmates were cult members, and that flames engulfed his bedroom.

His tireless father, Charles Laudor, talked him through these delusions, acting as a constant, despite Michael’s persistent belief he was a Nazi.

As he descended deeper into madness, threatening to kill his mother, Laudor found himself in a locked psychiatric ward at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center.

For eight months, Laudor believed the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele (known as “the Angel of death”) roamed the halls preparing to lobotomize him without anesthesia.

Finally diagnosed with Schizoaffective disorder, Laudor was treated with antipsychotic medication, known as neuroleptics, and released to a halfway house, and then back into society, without longterm psychiatric care, or any other therapeutic measures.

Before he was hospitalized, Laudor was accepted to Yale Law School. Against his doctors' advice to pursue simpler employment like a Macy's cashier job, his devoted father, and those in his orbit, urged him to go.

They assumed that his brilliance would save him, that the fiercely intelligent young man they’d known all this time was still inside and just needed to be released.

The neuroleptics came with a host of debilitating side effects, and interfered with his cognitive and physical abilities. Yet classmates, professors, his father, and even the Dean worked tirelessly to ensure his success, reading complicated legal texts aloud and typing papers when the medications caused his fingers to stiffen–extraordinary accommodations seldom afforded to women or people of color.

Laudor later remarked he attended "the most supportive mental health care facility that exists in America: the Yale Law School."

Laudor before psychosis and Laudor after psychosis were two different versions of Michael Laudor, yet Rosen makes clear that rather than benefiting from being seen for who he became after falling ill, Laudor was coddled and enabled to approach learning with the same intensity as before his mental illness and medication–an approach only one professional in his cohort dared question before being disregarded.

His accomplishments were inspiring. That he had Schizophrenia made him the most palatable kind of mental health success story. In 1995, upon graduating Yale Law School, he was profiled by Lisa W. Foderaro for a New York Times piece, instantly transforming him into a symbol of triumph over adversity, suggesting with proper support, even the most severe mental illnesses could be overcome. His story paved the way for a $1.5 million deal with Ron Howard to dramatize his life, with Brad Pitt playing the lead role, and a $600,000 memoir deal with Scribner.

While a windfall by all measures, even the heartiest individual would suffer from such high-pressure stress, and Laudor was no exception. Not long after, he began suffering from Capgras delusion–the belief his fiancée Caroline "Carrie" Costello had been replaced by an impostor determined to kill him.

On June 17, 1998, after failing to write his memoir, even with the help of a full-time editor, and suffering from deepening depression, the medication either stopped working well, or he went off it entirely, and in a devastating psychotic break, he bludgeoned his fiance Carrie to death, believing she was a wind-up doll with plans to murder him.

It was only after the fact that their friends, including Rosen, learned she was pregnant with their first child.

Michael Laudor and his fiancée, Caroline Costello, in a photo found by the police in their apartment in Hastings-on-Hudson (Photographer unknown; Tolga Tezcan / Getty)

Michael fled 220 miles from his Hudson Valley home to Cornell University, where he’d spent a blissful summer at the Telluride Association in high school, and waved down police to confess.

He was found unfit to stand trial, and was sent to the Mid-Hudson Forensic Psychiatric Center, where he remains today.

Bookending the glowing piece about him in the New York Times, the New York Post, demonstrated the despicable way the media narrative of mental illness in America gets shaped and perpetuated .

Rosen uses Laudor's story to explore the ethics of psychiatric care, and societal stigma while offering a stark critique of America’s mental health care system, and the myriad ways the system failed his best friend.

He explores America's fragmented, underfunded system, how it lacks integration between hospitals, outpatient clinics, housing, addiction services and rehabilitation programs.

State psychiatric hospitals began closing in the 1950s as institutions outgrew their capacity for care, and more doctors were drafted. This staffing shortage gave rise to extremely poor conditions.

Other factors included the rise of neuroleptics, and a strong marketing campaign for anti-psychotics led people to believe that mental illness could be completely controlled by drugs.

The establishment of Medicaid in 1965 was a driving force behind the transition from inpatient to outpatient mental health services. A crucial aspect of the Medicaid legislation prohibited the use of federal funds for inpatient care at psychiatric hospitals. This financial disincentive compelled states to shift away from expensive state-run inpatient facilities for the mentally ill.

When the Community Mental Health Act passed two years earlier in 1963, it laid out a vision to phase out large psychiatric institutions in favor of community-based treatment centers.

The aim was to enable those suffering from mental illness to receive care while remaining integrated within their local communities.

Michael Laudor after bludgeoning Carrie Costello | Credit: New York Post

These two landmark policies of the 1960s, cutting off federal funding for state psychiatric hospitals while promoting community-based care, propelled the deinstitutionalization movement that sought to reduce the United States' over-reliance on institutionalizing the mentally ill.

However, this transition to community-based care was poorly implemented, lacking sufficient funding, housing, and rehabilitation programs.

Many mentally ill individuals were released without support, contributing to homelessness, poverty, and drug addiction. A crackdown on petty crimes led to jailing those exhibiting erratic behavior, disproportionately affecting the mentally ill. This perpetuated the stigma that they are dangerous criminals needing to be controlled.

The American mental health care system over-relies on medication and crisis management rather than holistic, rehabilitative care. Evidence-based models for coordinated community treatment teams and supportive housing exist but are severely underfunded, reaching only a fraction of those needing these services.

What Michael Laudor needed, Jonathan Rosen claims, in this Atlantic article, was “a respite from tormenting delusions—that his fiancée was an alien, that his medication was poison.”

Law enforcement officers typically lack specialized training to handle mental health crises, yet they are the ones called to respond when someone dials 911 for such emergencies.

The legal bar for arresting an individual is remarkably low, while the threshold for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization is exceptionally high. Consequently, jails and prisons have effectively become substitutes for emergency mental health facilities across the nation.

This is a staggering overrepresentation compared to the general public, where only around one-fifth of people live with a mental health condition. This disproportionate phenomenon highlights a crisis within America's criminal justice system when it comes to appropriately addressing mental illness.

The Best Minds is a powerful call to reevaluate how we approach mental illness as a nation.

Rosen's masterful storytelling and insights make this crucial reading for anyone interested in psychology, literature and the ethics of care.

Through Laudor's tragic tale, Rosen memorializes a brilliant but troubled friend while advocating for more humane, effective mental health solutions. In doing so, Rosen illuminates the enduring strength of friendship and the imperative of compassion when confronting mental illness.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this book, and the system of care in America. Let me know in the comments!

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade