Feeling overwhelmed by the long articles? Have no fear; TL;DR is here! This new end-of-the-month digest summarizes the vital bits from this month's "How to Live" newsletter, so you don't miss a thing.

Does this sound familiar?

"I've spent the past decade screwing up my entire life, and now I'm too old–not to mention stupid–even to TRY getting what everyone around me has. I am physically repulsive, broken, dysfunctional, and too unsuccessful for anyone to want to marry me. I might as well not even exist."

This, my friends, is your brain playing your antagonist, and it has a name: Cognitive Distortion.

Cognitive distortion drops a colored lens over your eyeballs and leads you around, viewing everything in the monochromatic shade of blargh. Believing your cognitive thoughts leads to negative thinking.

When we treat our negative thoughts as the Torah scroll of truth and abide by them, we convince ourselves of things that are neither helpful nor factual.

In the 1960s, psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck developed the Theory of Cognitive Distortions. During interviews with depressed patients, he noticed themes and patterns threading throughout their stories. Their perception of events was distorted and filtered through a lens of negativity and self-criticism. Their first thought automatically linked their self-worth to the adverse event. He called this style of subjective filtering COGNITIVE DISTORTION.

Early messages help form our core beliefs. In other words, we base our assumptions about the rest of the world upon what was modeled for us when we were young.

CBT helps people think in a more balanced way. It’s based on the theory that the way people read situations has more to do with their reactions (or overreactions) than with the situation itself. CBT helps train us to step back and look at the fuller picture.

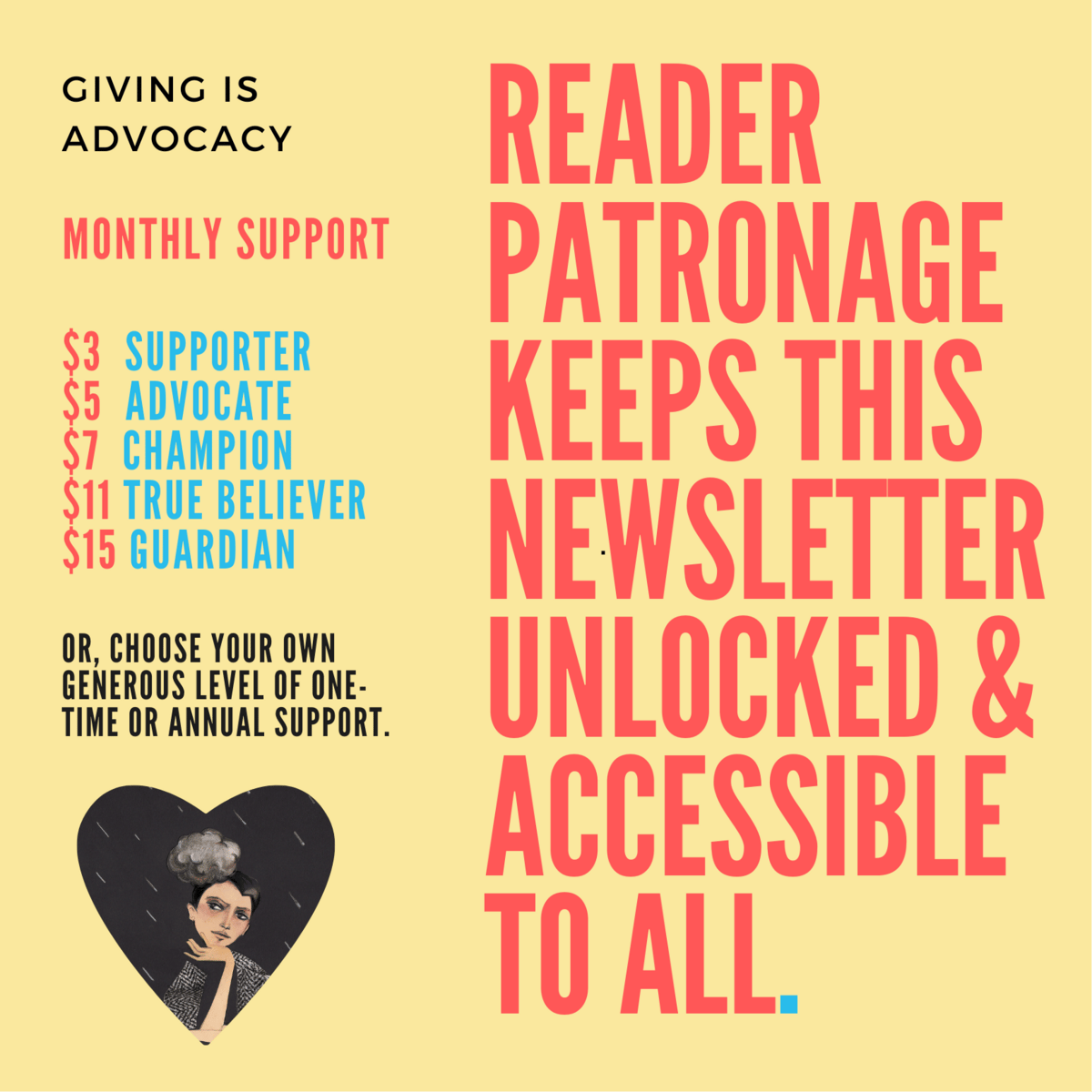

HOW TO GIVE: If you find value in this newsletter, please consider a donation. I rely on your support to keep these resources unlocked and available. I spend almost 300 hours a month researching, reading, writing, and producing these pieces, pouring considerable resources, money, and energy into each one. Every dollar helps keep this newsletter alive. THANK YOU.

A trauma bond is a relationship between two people that cycles through a pattern of abuse followed by love and affection. This relationship pattern often begins with an over-the-top style of courting (some people call this "Love bombing"), and it follows a cycle:

Love bombing / Gaining Your Trust / Criticism and Devaluation /Gaslighting / Resignation & Submission / Loss of Sense of Self / Emotional Addiction

WHERE DID IT COME FROM?

Growing up in a chronically stressful environment keeps a person stuck in a fight-or-flight state. Their system is flushed with stress hormones, and like anyone who is chronically frightened, their focus is on finding relief. They may find that people-pleasing or being “good” will get them the affection or nurturing they need.

This specific dynamic of being loved and cared for after periods of abuse is the signature feature of a trauma-bonded relationship.

Leon Festinger developed the theory of cognitive dissonance in the 1950s. It describes the discomfort a person experiences when they hold two conflicting beliefs. The term “trauma bonding” was coined by Patrick Carnes, the founder of the International Institute for Trauma and Addiction Professionals (IITAP)

Trauma bonds eradicate a person’s self-image and sense of individuality, which makes it easier for them to internalize and believe their abuser’s warped view of them. This is how someone loses their sense of autonomy and agency.

The more trauma you’re exposed to, the less it feels like trauma, and your brain prefers it that way. Obsessing over people that have hurt you even after they’ve gone is a common sign of a trauma-bonding relationship. Being unable to walk away from unhealthy relationships is also a sign.

GETTING OUT:

Educate yourself on what a healthy relationship looks and feels like. It’ll blow your mind while also giving you a road map for what to look for going forward

The types of therapy that work well for trauma bonding are trauma-based: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, Somatic Experiencing, or any therapy whose practice is predicated on understanding trauma.

HOW TO GIVE: If you find value in this newsletter, please consider a donation. I rely on your support to keep these resources unlocked and available. I spend almost 300 hours a month researching, reading, writing, and producing these pieces, pouring considerable resources, money, and energy into each one. Every dollar helps keep this newsletter alive. THANK YOU.

This piece from January 18th revealed the myth of the average human being.

It's 1945 in Ohio. You catch an intriguing headline in The Cleveland Plain Dealer:

“Are You Norma, Typical Woman? Search to Reward Ohio Winners.”

Who is Norma? And what does it mean to be Norma? But more importantly, are you Norma?

As you read, you discover that this typical woman, Norma, possesses the ideal female form in all nine dimensions: height, weight, bust, waist, hips, thigh, calf, ankle, and foot.

Who knows, perhaps you are Norma, whose nine dimensions are ideal!? Maybe you could be rewarded with the money or war bonds they’re offering just for being the “typical woman.”

Just one thing--Norma is a statue.

SAY WHAT?

In 1940, the Bureau of Home Economics was looking to create a standardized system for sizing readymade clothes. To do so, they collected nine dimensions of over 18,000 “native white” women between the ages of 21 and 25.

Dr. Robert L. Dickinson, a celebrated gynecologist-obstetrician at the time, used this data amassed by the Bureau of Home Economics for an entirely different purpose. His goal was to create the ideal woman by tallying up the thousands of data points, calculating the statistical average of that data, and based the Norma statue on the final nine dimensions.

That's right, the dimensions of the "average and ideal woman" were created by a white gynecologist, who averaged the numbers of 18,000 "native white" women to arrive at the form of the ideal woman.

The contest, to find the woman who most closely hewed to these farcical dimensions, would be crowned the ideal woman and given money.

Over 3,800 women applied.

The contest judges assumed they’d be in for all-nighters, believing that most contestants would meet or come close on all nine of Norma’s dimensions. How would they choose when so many women met these standards?

They needn’t have worried.

Less than 40 of the 3,864 entrants met even five out of nine dimensions. Not even Martha Skidmore, the theater cashier who won the contest, matched all nine dimensions.

How could this have happened?

The contest itself was flawed. There is no such thing as an "average woman," yet, instead of seeing the contest as flawed, doctors and government health agencies viewed the women as flawed and chastised them, berating them into exercise programs and prescribing diet pills.

I found this story, in this life-affirming book, The End of Average, by Todd Rose.

HOW TO GIVE: If you find value in this newsletter, please consider a donation. I rely on your support to keep these resources unlocked and available. I spend almost 300 hours a month researching, reading, writing, and producing these pieces, pouring considerable resources, money, and energy into each one. Every dollar helps keep this newsletter alive. THANK YOU.

This piece from January 25th offers an interesting shortcut to self-awareness called The Johari Method

Two American psychologists, Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham were interested in interpersonal dynamics in group settings. They understood that interactions between members are shaped by differing perceptions and wondered whether they could develop a tool to foster alignment among members and reveal their blindspots and differences.

They believed with the proper framework that they could help people be more effective at work and more authentic in life.

In 1955, they introduced what they called the “Johari Window Model”—a portmanteau of the first two syllables of their names—a tool to bring strengths and weaknesses to the surface, foster self-awareness, interpersonal communication, engender sensitive feedback, and bring mutual understanding to groups.

The Johari Window is an exercise that consists of four quadrants: the Open Area, the Hidden Area, the Blind Spot, and the Unknown, as well as a list of 55 adjectives from which a user is to choose five or six to describe themselves and others.

Here’s how it works:

From the list of the 55 adjectives, the subject chooses 5 or 6 adjectives to describe themselves. The other members also choose 5 or 6 adjectives from the list to describe the subject’s personality. Everyone writes down their chosen words on their piece of paper. When everyone is done, the friends share the words they chose.

If any adjective you chose to describe yourself overlaps with anyone else, those words all go into the box marked OPEN. The words you chose that your friends didn’t go into the BLIND box. You can share during the process if you feel like it. The words that your friends chose that you did not go into the HIDDEN box. All the rest of the words from the list are UNKNOWN to you. Of course, they are within you somewhere; they just haven’t come out to play!

The more you talk and reveal about yourself, the more you become known, and the goal is to expand the OPEN quadrant for every person.

But we don’t need to do the Johari Window exercise to derive its value. We can use the questions it’s asking in every situation.

You can increase your self-awareness and self-perception by constantly and consistently asking yourself these questions:

What do I know?

What do I not know?

What do other people know?

How do I find out what I don’t know?

We often believe we have the complete picture based on half the information. Think about how often we hear stories about breakups—romantic or platonic. Usually, we’re privy to only one version, and we tend to accept it at face value without reminding ourselves that there is more we don’t know because there is more our friend doesn’t know.

There is always another point of view, and there are always blind spots and hidden details. When our loved ones confide in us, we believe them—as we should. At the same time, it would serve us well to remember that everyone has blind spots.

When we ask what we don’t know about ourselves, about every situation, the moods of others, or how we were treated and how we treat others, we expand our self-awareness and understanding of others.

HOW TO GIVE: If you find value in this newsletter, please consider a donation. I rely on your support to keep these resources unlocked and available. I spend almost 300 hours a month researching, reading, writing, and producing these pieces, pouring considerable resources, money, and energy into each one. Every dollar helps keep this newsletter alive. THANK YOU.

DID YOU KNOW I LAUNCHED an ONLINE-ONLY SERIES CALLED Dispatches From the Past?

Visit the website and discover new content resurrected from the past. I won't be sending these out (but they'll appear in the monthly TLDR roundup)

This piece from January 23rd attempts to lift even the lowest spirits with those who excel at their craft.