You’re reading The How to Live Newsletter, where we uncover the hidden psychological forces shaping our lives—and learn how to outgrow their influence.

Through deep research, personal storytelling, and hard-won insight, I challenge the myth of normalcy and offer new ways to face old struggles.

This newsletter is reader-supported. Consider a paid subscription for deeper insights, exclusive content, and seasonal in-person community gatherings if it resonates. ❤️

You can also donate any amount.

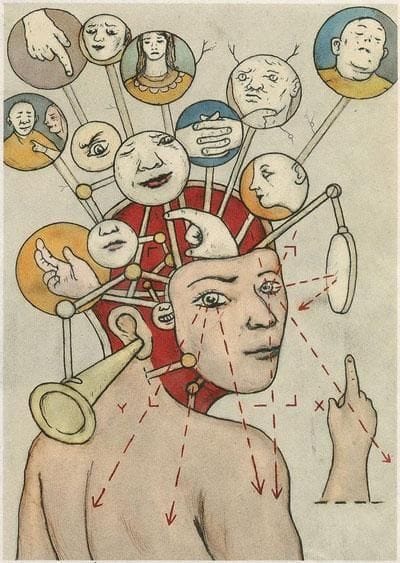

Vigilance as Vulnerability: The Exhausting Practice of Hypervigilance

I spent my entire childhood orbiting my mother on a hypervigilant 24-hour watch, ensuring she wouldn’t disappear into thin air, accidentally cross the street on red and get hit by a car, or forget she had a family and move to another country while we were sleeping.

This is why I slept in her bedroom for years—well past an appropriate age— jarred awake by the slightest rustle of a bedsheet. I am anxiously attached to the language of attachment theory, which states that the care given to babies by their primary caregiver influences how they’ll attach to their relationships as adults.

The circumstances into which we are born and the conditions in which we are raised create the blueprint for all future interactions and patterns of engagement and connection.

Not long after I was born, my parents separated and then divorced.

Perhaps that’s why connecting with people I love is intertwined with the threat of imminent loss. Who knows? Whatever the case, something triggered my genetic predisposition for anxiety, and it flourished under the guidance of hypervigilance.

Hypervigilance itself is not a mental health condition. Instead, it’s a symptom associated with various mental health disorders, including PTSD, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and mood disorders.

To experience hypervigilance means being in a chronic state of high alertness. And prone to overreaction.

It is being primed for war, ready to run or hide at a moment’s notice, even when you're just sitting at dinner with friends and loved ones.

When anxious people feel that their attachments are threatened, they can grow hypervigilant about all their attachments.

As children, survival depends upon the caretaker’s survival, and an anxious baby will be constantly alert for confirmation that their caretaker is alive. I was continually scanning my environment for threats that might separate me from my mother, thinking that my hypervigilance and its accompanying worry would prevent her death, or my own, from whatever trauma might tear us apart.

As I grew and changed, this aspect of me remained the same; it simply attached and organized itself around different relationships.

Hypervigilance of this sort is a survival instinct, and to live inside of it is to remain emotionally dysregulated.

To live in modern society is to exist in a constant state of bombardment. We’re inundated by information, stimulus, and the mistaken belief that filling time is more important than experiencing it.

Because of the demands of contemporary life, we cannot truly digest responses as a whole or move through a complete experience. Many of us exist in a half-digested life. This keeps us stuck in an unfinished loop, and it’s there, in the interruption, the halfway point, that hypervigilance lives.

Without a way to move through this heightened state of arousal by self-regulating, we are often left to reach for something to numb or manage our emotions, including self-medicating, self-harm, or disordered eating.

When hypervigilant children grow up and edge out into the world, they scan their environment for things that signal whether or not they are safe.

In all relationships, but especially romantic ones, they are highly attuned to emotional and physical absences, anything that signals disconnection or feels dangerous, like neglect or exclusion, any small shifts that telegraph such a change.

These slights feel threatening, and the hypervigilant scanner, upon sensing they are being neglected or excluded (or whatever emotional signal they're most sensitive to), feels they need to protect themselves at whatever cost.

They either cling to the person they feel is disconnecting or flee.

The hypervigilant is overly aware of the body language, actions, and behaviors of their loved ones.

Here’s what it looks like.

My most profound insights don't go in the free version—they're distilled from my 27 years in therapy, decades of independent study, and work as a mental health advocate. These deeper dives are reserved for readers committed to going deeper.

Join How to Live

Transformative concepts from a lifetime in therapy.

Get Immediate AccessA subscription gets you:

- All articles the moment they're published

- Instant access to the entire archive of 150+ posts

- Occasional bonus posts

- Invitations to seasonal in-person events

- Direct email access: get personalized resource recommendations + advice (ANNUAL PLAN ONLY)

- 15% off all workshops