You’re reading How to Live—an inquiry into the psychological forces that shape us, and how to stop being run by them.

Through deep research, personal storytelling, and hard-won insight, I challenge the myth of normalcy and offer new ways to face old struggles.

This work is reader-supported. If it speaks to you, consider a paid subscription for deeper insight, off-the-record writing, and seasonal in-person gatherings.

You can also donate any amount.

How to Live Relies on Reader Support to Survive

I invest over 300 hours and hundreds of dollars out of pocket each month running this newsletter, and your help is essential.

Here's how you can make a difference:

DONATE: Give a one-time, annual, or monthly recurring donation in ANY AMOUNT. ($6+ a month unlocks bonus content and in-person members-only events, drinks, and dinner invites.)

UPGRADE: Join for $6 a month.

Your contribution sustains this project, covering its costs and keeping the weekly Wednesday pieces paywall-free and accessible to all. Let's continue filling the gap in mental health resources together.

❤️ THANK YOU ❤️

Every Day is a Performance of Self For Others

Many among us agonize over the existential limitation that we can never fully experience another's inner world, experience and feelings.

This means our own subjective human experience also remains entirely unknowable to others.

The closest we come is to perform the self we wish others knew, but acting oneself isn't an adequate conduit; instead, it's a mediated form of selfhood.

Much of life is spent trying to close the gap between the self we understand ourselves to be and the self others perceive.

We tell people what we want them to believe about us, and our behavior matches, creates congruence, or signals incongruence. What we wear, how we wear it, how we respond, and position ourselves in space are signals, signposts we use to mediate how people see us.

There is a primal divide in us—the person we are versus the story of us we were raised to believe.

Every examined life dedicates itself to unearthing the original self before our narratives get shaped and cemented, to removing the accumulated symbols, signifiers, costumes, attitudes, and codes placed upon us by others.

Feeling misunderstood is the core sense of many people's lives (hello, it's me). Often, there is a distance between what we say and how we behave, and it's in that gap that a person is understood.

Ironically, in our effort to be known, we perform the self we wish others knew, thwarting the motive, our deepest desire, to be known.

Like Rilke’s letters on solitude, we are all uniquely alone.

You can never feel the exact texture and shape of my sadness, joy, or anger, as I can never feel yours. Everything is an approximation, yet we work hard to control our audience's perception of us, hoping for exactitude.

There is little more cliché than wearing a mask in public, of the world being a stage on which we all perform. Yet, the overuse of a cliché signifies its historical necessity and resonance with the human experience.

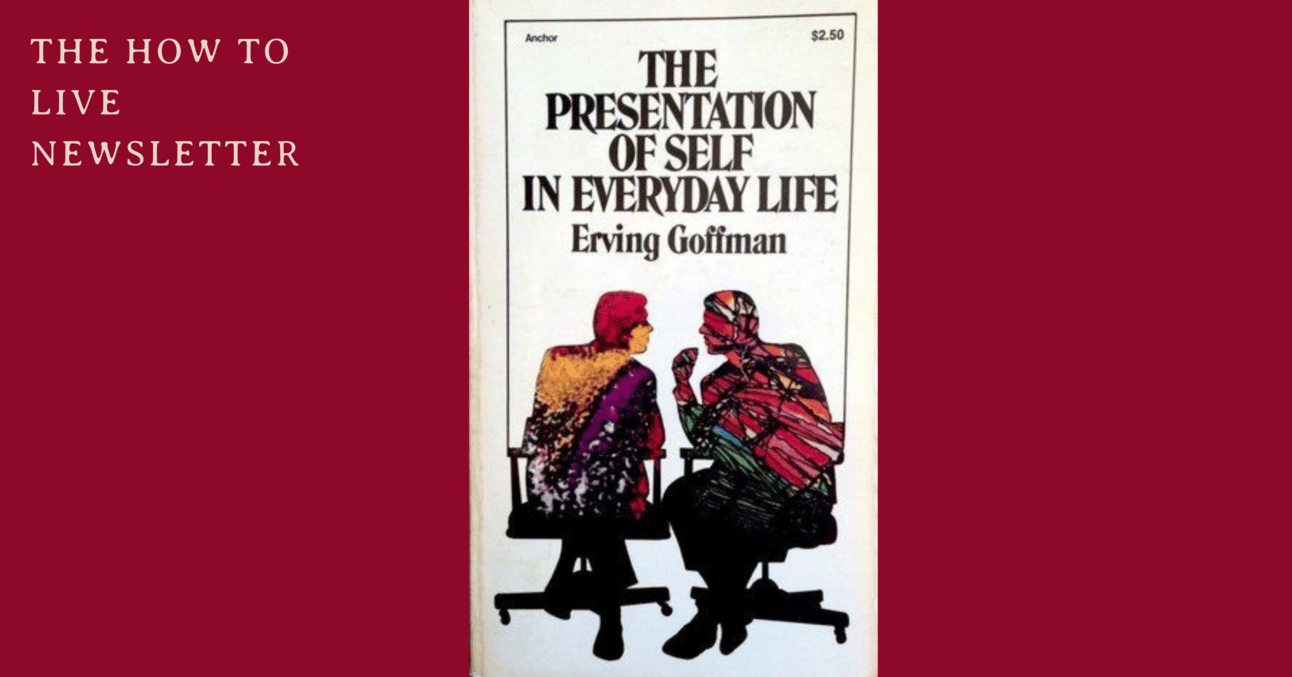

While we can thank or damn Shakespeare, it was the brilliant mid-century sociologist Erving Goffman (the 73rd president of the American Sociological Association) who took that cliché and unpacked it, revealing how elaborately and seamlessly our disguises are woven into the fabric of human interaction.

Here’s what his most famous book tells us…

Goffman examined the self through a dramaturgical lens in his seminal 1956 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. He proposed that we are all performers playing innumerable parts across the stages of daily existence, constantly slipping into new theatrical identities built of gestures, costumes, speech patterns, and strategic self-censoring.

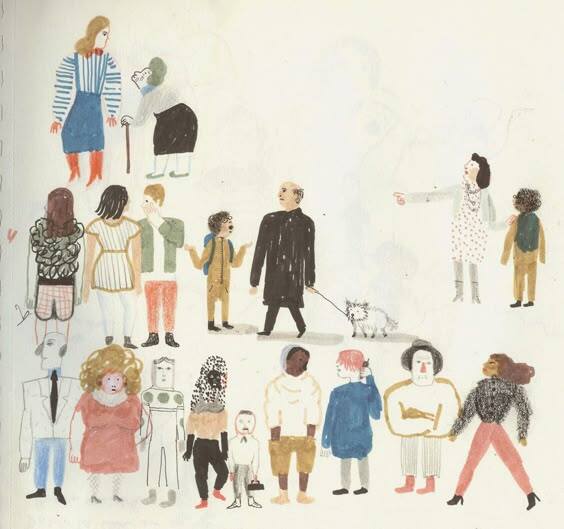

A cornerstone in the field of sociology, specifically within the study of symbolic interactionism, his exploration of the intricate dynamics of social interactions through the metaphor (and, sorry, the cliche) of theater proposed that individuals in society are like actors performing on a stage.

Individuals present themselves in ways others will accept and validate, meticulously managing their self-image in various social contexts. Goffman's central metaphor was that people performed versions of themselves calibrated for different social settings and situations. (What a field day he'd have with social media.)

From familial roles to professional personae, we are constantly slipping into new theatrical identities built on gestures, costumes, speech patterns, and strategic self-censoring. The effort of your friend’s new boyfriend as he warmly engages her friends, the confident podcast producer humble-bragging about his leadership style—these are just two frozen sketches from an infinite improvisational repertoire.

When an individual comes in contact with other people, that individual will attempt to control or guide the impression others might make of him by changing or fixing their setting, appearance, and manner.

At the same time, the person the individual interacts with is trying to form and obtain information about the individual.

The second person attempts to form an impression of, and obtain information about, the first person. Goffman also believed that participants in social interactions engage in certain practices to avoid embarrassing themselves or others.

Society is not homogeneous; we must act differently in different settings.

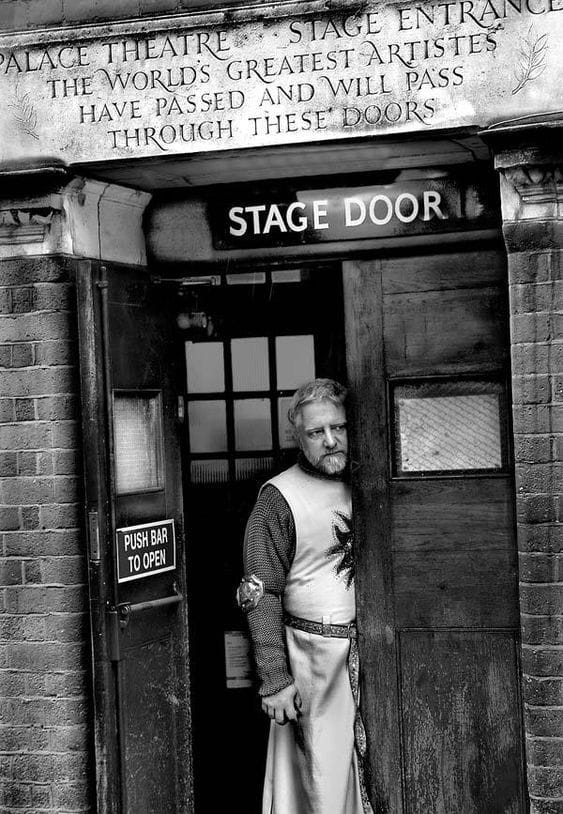

This recognition led Goffman to his dramaturgical analysis. He saw a connection between the kinds of "acts" people put on daily and theatrical performances. In social interaction, as in a theatrical performance, there is an onstage area where actors (people) appear before the audience (people in the world), offering positive self-concepts and desired impressions.

Born to immigrant parents in a hardscrabble Canadian farming village, Goffman felt attuned to the economic and social circumstances that dictated mask-wearing.

His mother pawned her treasures to pay the rent; his father toiled in menial factory jobs until a stroke rendered him voiceless.

Such tribulations left an indelible impression on the young Goffman's psyche.

Sociologists view identity as inherently fragmented, something we reconstruct and re-embody with each conversational dyad.

We are not whole, authentic selves moving through the world; we are canny performers calibrating our behaviors by minute status, audience, and setting calculations.

A preoccupation with external impressions eclipses our interior sense of self. Like actors in a green room, we adjust makeup, wardrobe, and motivation to suit the upcoming scene.

Goffman saw all social interactions as performances. Like actors, we manage our appearance, speech, and behavior to influence how others perceive us. We rely on a series of conscious and unconscious performances seeking to control the impression we make on others. Goffman called this “Impression Management.”

This management is not limited to face-to-face interactions but extends to various social settings and individual roles.

Goffman categorizes these performances into two regions: the "front stage" and the "backstage."

Front Stage: This is where the individual performs and adheres to conventions that have meaning to the audience. Here, people are aware of their audience and actively present themselves favorably.

Back Stage: In this area, individuals retreat and express aspects of themselves they suppress on the front stage. Here, they prepare for their performance and can behave in ways that would be inappropriate or unexpected on the front stage.

Goffman uses numerous examples to illustrate his concepts:

1. Service Workers: He discusses how service workers, such as hotel staff, perform on the front stage by maintaining a polite and helpful demeanor, even if they might feel otherwise. Backstage, away from guests, they can drop this façade and express their true feelings.

2. Medical Practitioners: Doctors maintain a professional and authoritative demeanor when interacting with patients in a medical setting. Backstage, among colleagues, they may discuss cases more candidly and express uncertainties or frustrations.

3. Social Gatherings: At a party, hosts perform by ensuring guests are comfortable and entertained, showcasing an organized and welcoming environment. Behind the scenes, they are stressed and hurriedly managing last-minute preparations.

Goffman's work, which may seem dated and cliché today, was revolutionary.

It integrated sociology, psychology, and anthropology and provided a comprehensive framework that reshaped our understanding of human behavior in social contexts.

Its influence was not confined to a single discipline but was interdisciplinary, leaving a lasting impact still felt today.

He shifted the focus of sociology to the micro-level of individual interactions, emphasizing the importance of everyday social exchanges in shaping larger social structures.

Goffman's proposition that the self is not a static entity but a dynamic construct that changes depending on social context and audience was revolutionary. It introduced a new perspective, challenging conventional wisdom and opening up new avenues for understanding human behavior.

The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life made visible our invisible social norms, highlighting unspoken rules governing behavior and revealing social life's mechanics, and it remains a pivotal work in understanding the complexities of social interaction.

While Goffman's work revealed the invisible rules of normativity, it also defied conventional methodological norms.

His sources were often vague, his fieldwork appeared minimal, and he preferred novels and biographies over scientific observation.

His writing style was more essayistic than scientific, and his approach wasn’t very systematic. He belonged to no distinct school of thought, so placing him within the social theory is complex, enhancing his image as an unconventional thinker (my favorite kind).

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this concept, and whether you are familiar with Erving Goffman. Let me know in the comments!

Until next week, I will remain…

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade