Art as Liberation: How a Viennese Psychiatric Institute Became a Sanctuary for Creativity

If I could have worked without this accursed disease, what things I might have done.

Art and mental illness have always intersected. Perhaps the best example is Vincent Van Gogh, whose psychologically charged work reflected his inner demons. Most of us are familiar with the story of Van Gogh cutting off part of his ear.

You may not know that he did it in response to feeling abandoned by Gauguin, whom Van Gogh had invited to start an artist colony in France. Initially idyllic, Gaugin and Van Gogh lived and worked side by side in a little yellow house in Arles, France. His friend's erratic behavior soon troubled Gauguin, and he announced he was leaving.

The threat of his friend's imminent departure perhaps triggered a deep agony in Van Gogh, and he reacted by severing a part of himself.

Ear in hand, Van Gogh walked to his local brothel and asked a young woman to keep it safe for him. He remembered nothing of the incident, and while his friendship with Gaugin remained somewhat intact, it was never the same.

Van Gogh's mental state was clear in his art. Even he saw it, remarking to a friend in one of his last letters before ending his life by suicide:

Art has long tried to make sense of troubled states (See: The Rorschach Test). And troubled states have long influenced art.

In 1898, on the outskirts of Vienna, Austria, a psychiatric institute called the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic opened its doors.

The institute had a particularly troubling past. Forty-two years after its founding, the Nazis used the site for their involuntary euthanasia program, Aktion T4. This program called for experimenting on and exterminating people with mental or physical disabilities. The Nazis abused and murdered hundreds of people with mental health conditions at Gugging.

That the clinic survived and then thrived is a miracle unto itself.

In the 1950s, Dr. Leo Navratil was a psychiatrist at the clinic. To better understand his patients, he inadvertently created a way to humanize mental illness, expand therapeutic forms, and contribute to the Art Brut movement.

Devoted to his work, he read and researched ways to help his unresponsive patients. After reading Karen Machover's book, Personality Projection in the Drawing of the Human Figure, he created a nonverbal measure to assess and diagnose personality and mental states. He asked his patients to draw a person.

What his patients did in response forever changed the landscape of mental health care.

Many of his patients drew more than just a simple figure, as Dr. Navritil assumed. Drawing brought forth their diverse inner worlds of torment, uncovering the hidden language of their emotional pain.

He noticed a striking resemblance to their emotional states as he studied their work. Johann Hauser, a longtime patient who lived with schizophrenia, depicted his manic and depressive episodes in his drawings.

This helped Dr. Navratil to understand his patients' suffering better. By granting them the freedom to express themselves, Dr. Navratil tapped into an underworld, a depth of emotion he might otherwise not have found.

Through creation, a powerful defiance against societal stigmas and constraints emerged. His patients confronted their inner struggles in each line, brush stroke, or shape. They discovered solace and gradually reshaped their narratives with shades of hope. The craft took on a life beyond conventional therapy, transforming into a potent instrument for self-realization and liberation.

In recognizing the utility of art to transcend the barriers of mental illness and provide a platform for self-expression, self-discovery, and healing, he began prescribing art as therapy.

He couldn't help but notice how talented many of his patients were, and as seriously as he took their mental health, he took their work. He began calling them The Gugging Artists.

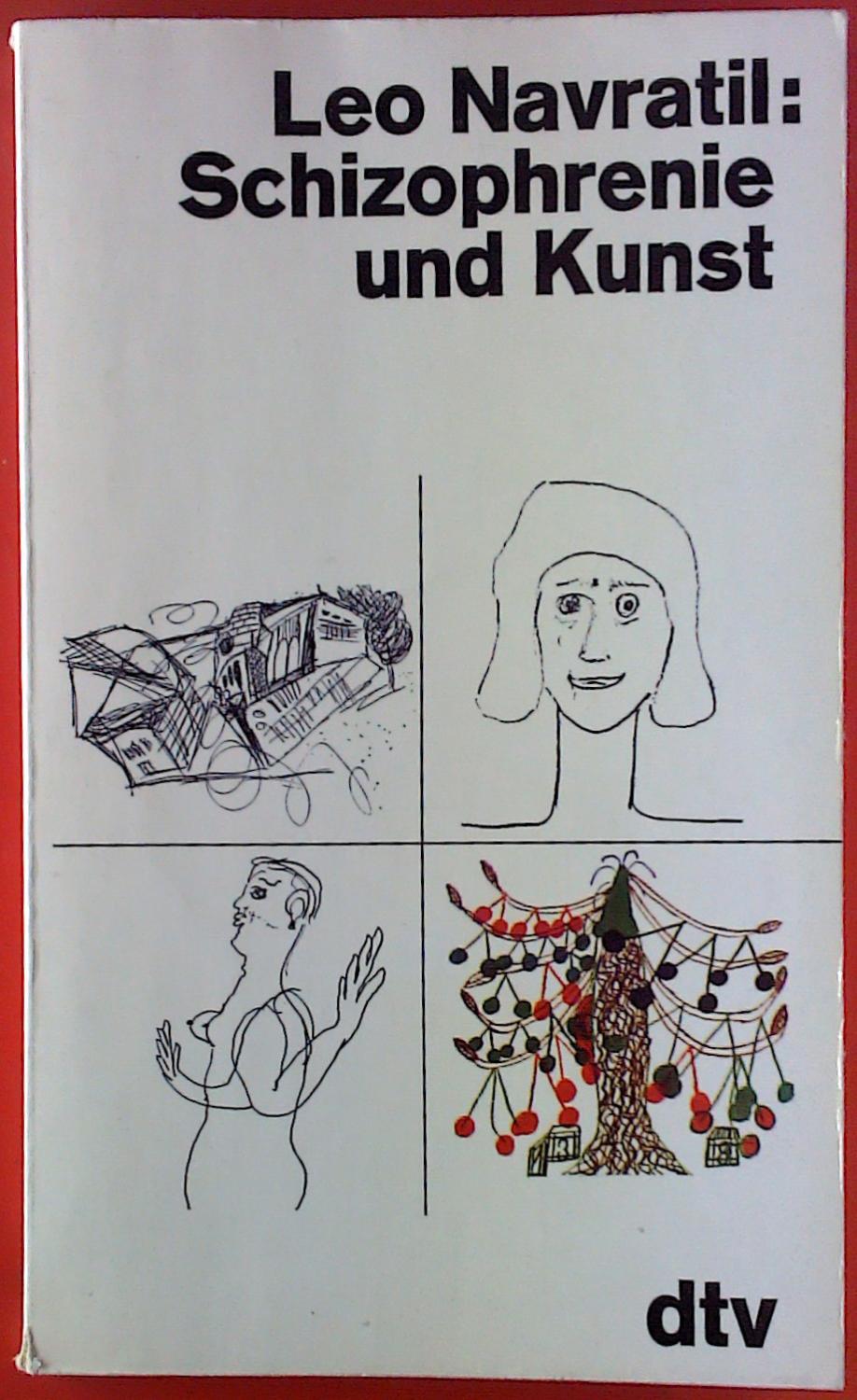

In the 1960s, he began introducing their art to the world, and in 1965 he published a book called Schizophrenia and Art. This book brought the attention of visual artists who were part of the Viennese avant-garde.

They were early and ardent supporters and helped catapult the Gugging Artists into the public realm (David Bowie and Brian Eno visited in 1994 and used the institute as the primary source for Bowie’s album Outside).

In 1970, the Gugging artists organized an inaugural art exhibition at the esteemed Viennese Galerie Nächst St. Stephan, drawing attention from local and international contemporary artists.

The exhibition included works by the first generation of Gugging Artists,

As they began gathering acclaim, Dr. Navratil reached out to the artist Jean Dubuffet, who, in 1945, had coined the term "art brut," which translates to "raw art" or "outsider art."

According to Dubuffet, a work qualifies as Art Brut when an untrained self-taught individual makes it. This person must operate outside of traditional artistic norms and academic influences. The art must emphasize authenticity, spontaneity, and raw expression. It embraces the creations of individuals with limited or no connection to mainstream art.

Jean Dubuffet confirmed that the Gugging artists were making art brut and included them in his collection.

As the artists at Gugging became more celebrated, Dr. Navratil wanted to upgrade his artist patients' living and working conditions. In 1981, he established the Center for Art and Psychotherapy. The Center was a residence and a dedicated space for the now-famous original "Guggingers" to live and work.

In 1986, Dr. Navratil retired, paving the way for his successor, the artist Johann Feilacher, to transform the Center for Art and Psychotherapy into The House of Artists.

Recognizing the need for a shift in focus, Feilacher believed that artistic talent should take center stage rather than mental illness and art as therapy. While Dr. Navratil had taken bold steps forward and saw his patients’ drawings as art, he never quite separated their mental illness from their work. He referred to their output as “State-bound art,” meaning “mental state.”

Johann Feilacher, also a visionary, saw what Dr. Navratil couldn’t—the Gugging artists should not be bound by their mental states. By removing the stigma and separating the patients' art from their mental states, they could transcend their conditions and blossom into genuine artists, free from perpetual confinement.

The Gugging Artists shed their former identity as "patients." They embraced their new roles as artists and residents of The House of Artists. This assisted living facility prioritized their individuality and creative abilities. Feilacher built upon Navratil's foundation, reimagining and expanding it to establish a new paradigm of living in art.

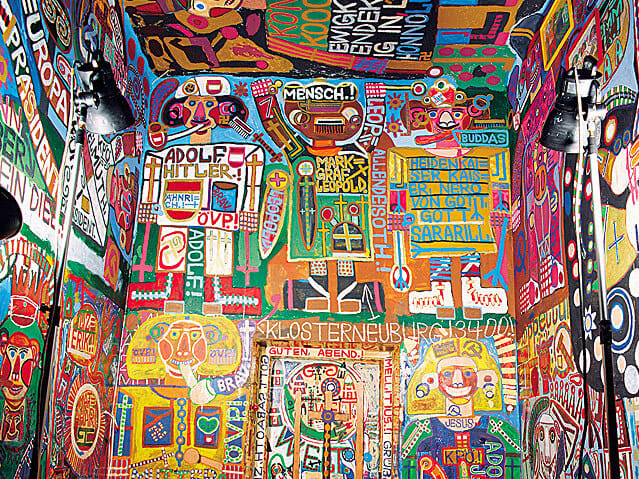

The Interior of the House of Artists

Feilacher firmly believed that the Gugging artists deserved recognition and acclaim equal to their peers. He championed the art, refusing to categorize it as a lesser subgenre. His efforts led to the inclusion of Gugging Artists' works in European exhibitions, carving out a space for their unique artistic expression.

In 1990, their remarkable contributions to contemporary art were honored with the prestigious Oskar Kokoschka Preis, cementing their place in the creative landscape.

Today, they have a gallery,a museum, an atelier, and permanent residents. The Gugging artists live a life of collective creativity and are considered some of the most renowned in the art brut field. In the past two decades, female art brut artists at Gugging have finally gotten exposure.

Museum Gugging

On the grounds of the hospital, 12 artists live full-time in the House of Artists. They earn money from the sale of their work, which goes into their bank accounts and is dispensed upon request. Feilacher’s model helped to de-institutionalize Austria and introduce the practice of community psychiatry.

The legacy of the Gugging Artists serves as an inspiration for embracing individuality, fostering inclusivity, and celebrating the beauty of artistic expressions that defy conventional norms.

Unconventional minds offer the potential to re-evaluate societal notions of mental health and what therapy can look like.

The most significant contribution of the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Institute lies in its openness to change, and the House of Artists can push us to redefine our understanding of normalcy.

Living in art challenges us to question the traditional boundaries of mental health. It reminds us that brilliance and beauty often emerge from unconventional minds. Diagnosis should not limit the human spirit; instead, we must transcend our imposed boundaries so that others can create a profound and lasting societal change.

The Gugging Artists and the House of Artists have left an indelible mark on the art community, challenging preconceived notions of artistic ability and reshaping the understanding of the hidden abundance inside the minds of those considered deficient. Art has power; it can transform a person's sense of self and bring them into healing.

We can challenge societal perceptions of mental health by emphasizing creativity and art therapy to foster inclusivity and celebrate the beauty of artistic expressions that defy conventional norms.

Let the legacy of the Gugging Artists serve as a resounding call to embrace individuality and the brilliance of variant minds.

Are you familiar with the Gugging Artists? What do you think of this innovative model? Let me know in the comments!

Until next week, I remain…

Amanda

Cover art by: OVITAL INFO:

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade