Happy New Year, dear subscribers.

For four+ years, I've published How to Live every single Wednesday, missing just one issue in 224 weeks. This isn't a side project. It's a research-intensive weekly newsletter that exists alongside the writing, teaching and coaching work I do to make ends meet.

I spend hundreds of hours each month reading psychological research, synthesizing ideas, and translating complex theory into something immediately useful. I do this because mental health resources are largely unaffordable and inaccessible, and I believe everyone deserves better.

How to Live costs $6 a month for access to an hundreds of articles—an entire archive—of psychological insight, what I call "citizen psychology." Everything I've learned from decades of therapy, reading, and my own hard-won understanding of suffering goes into this work.

If this work offers even one person a way through a dark thought, brief moments of relief, a zing of hope, then I'm doing what I'm meant to do.

But this work requires support to survive.

Your subscription doesn't just pay for my time, it covers the operating costs, over $5,000 annually for the hosting platform, design software, academic library memberships, academic journal subscriptions, social media scheduling tools, and the ever-growing miles of physical books I rely on to do this work well. It also allows me to offer free memberships to readers who can't afford $6 a month.

If you believe this work matters, if you recognize that while institutions fail us, ordinary people are picking up the mantle, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription this week.

This is how citizen psychology survives.

Yours in Brooklyn,

Amanda

To kick off the new year, I'm sharing a peek inside renowned science fiction writer Octavia Butler's personal diaries, where she practiced what's often called "manifestation" but might better be understood as radical self-recognition: naming who you are before anyone else does.

For everyone who feels their dreams are unattainable: this is the story of someone who understood that you don't become who you want to be. You recognize who you already are, and live from that truth until reality catches up.

Octavia Butler's Method for Reaching Impossible Goals

First forget inspiration. Habit is more dependable. Habit will sustain you whether you're inspired or not. Habit will help you finish and polish your stories. Inspiration won't. Habit is persistence in practice.

Octavia Butler used to wake up at 2 a.m. to write before her shift as a potato chip inspector began. It was the only time that belonged to her, the only time she could find to write, and it was there, in the margins of life that someone on the margins of society built not just a writing career, but a wild dream, into existence.

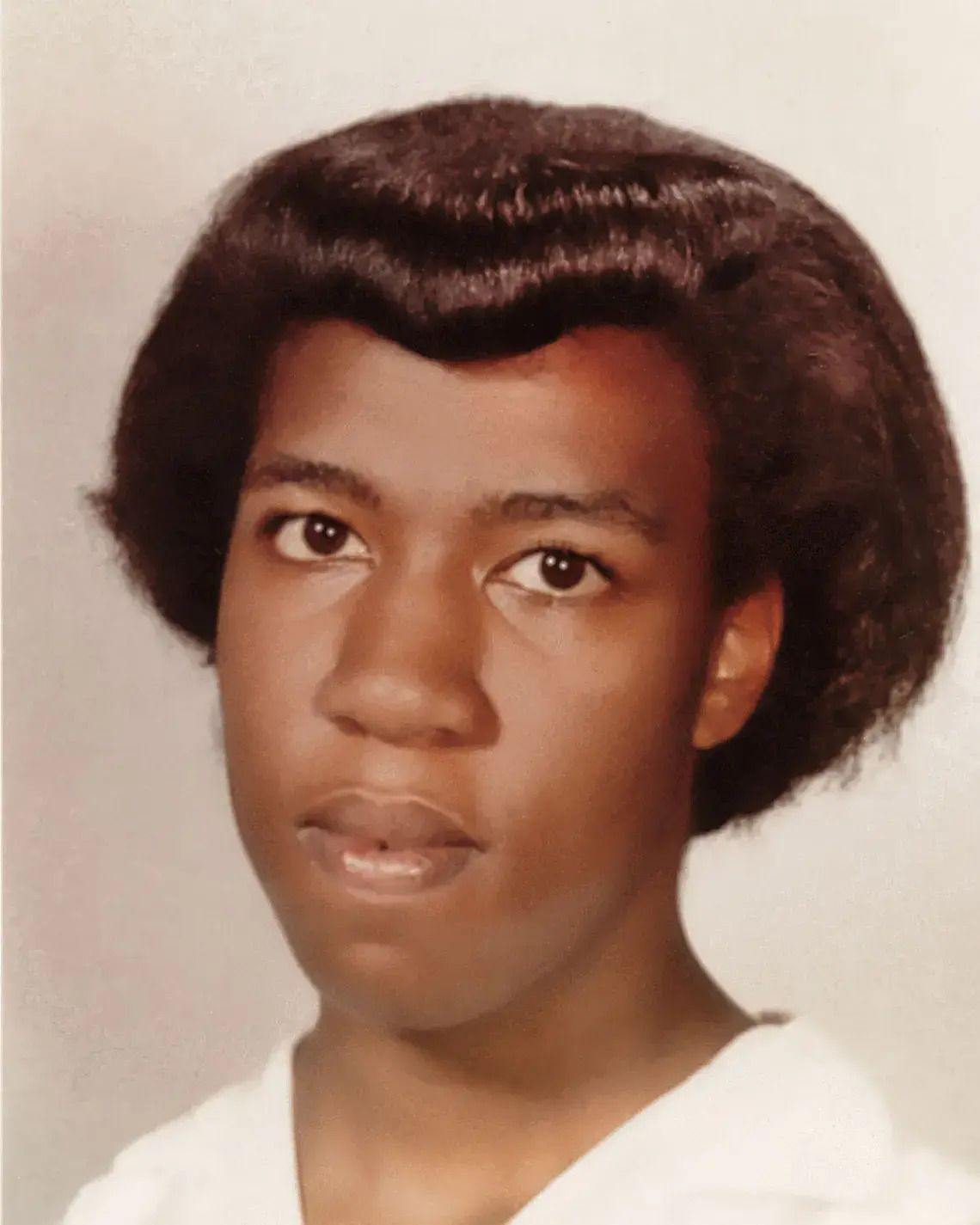

She was tall, 6 feet at least, and awkward. She was Black, dyslexic, poor, shy to the point of agony, and she stuttered when she spoke.

Born in 1947, she was in her early 20s in the 1970s, trying to break into science fiction, a genre that belonged almost exclusively to white men who went to the right schools and knew the right people. Butler had none of those advantages. What she had was her mother, who cleaned white people's houses until her hands peeled and cracked. This formative experience, watching her mother come home night after night, entirely beaten down, beset by an unbreakable exhaustion, became a driving force for young Octavia to never live that life.

Butler grew up in Pasadena, California, in a house where money was always tight. Her father died when she was seven, leaving her mother to raise her alone. As a Black girl in the 1950s and '60s, she experienced intense discrimination and bullying. She was always the odd one out: too tall, too quiet, unable to read as quickly as the other kids because of her dyslexia. Teachers assumed she was lazy or slow. When she wrote creative stories for school assignments, they were so unusual that teachers accused her of plagiarism, unable to believe this shy, struggling student had created something so imaginative.

But Butler found refuge in the library. Despite her dyslexia, she was a voracious reader, devouring science fiction and fantasy. At twelve, she watched a terrible B-movie called Devil Girl from Mars and had two revelations: "Somebody got paid for writing that story!" and "Geez, I can write a better story than that!" By age thirteen, a teacher finally recognized her talent and encouraged her to submit a story to a science fiction magazine. That submission, though rejected, planted the seed of a radical idea: she could become a professional writer.

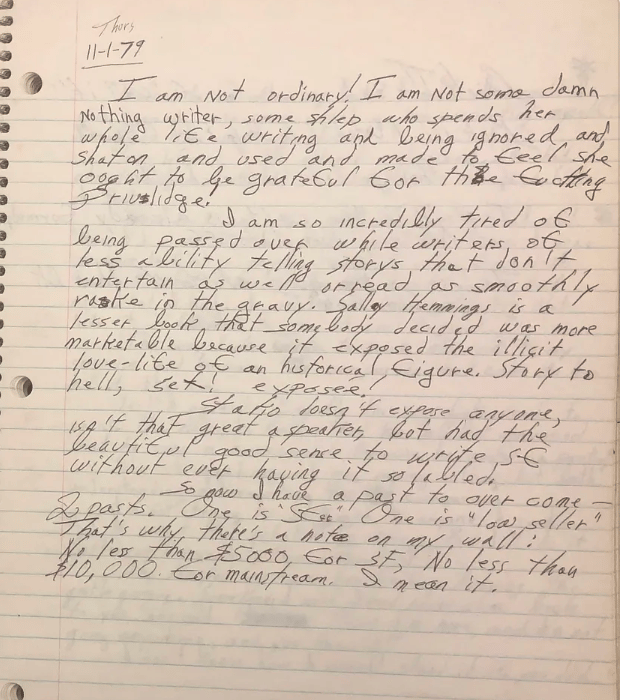

After graduating from Pasadena City College, Butler took whatever jobs she could find—dishwasher, telemarketer, warehouse worker, potato chip inspector. Jobs that paid the bills but left her free to think about her characters, and write in the middle of the night before work. The rejections piled up. Publishers didn't know what to do with a Black woman writing about slavery through science fiction, about power and survival and what it costs to stay human when the world tries to make you into something else.

Beneath it all, she was terrified. Terrified she wasn't good enough. Terrified she'd die in one of those factory jobs with her stories still trapped inside her. Terrified that everyone who told her this was impossible was right.

But, instinctively, she understood that a person can be afraid and do it anyway.

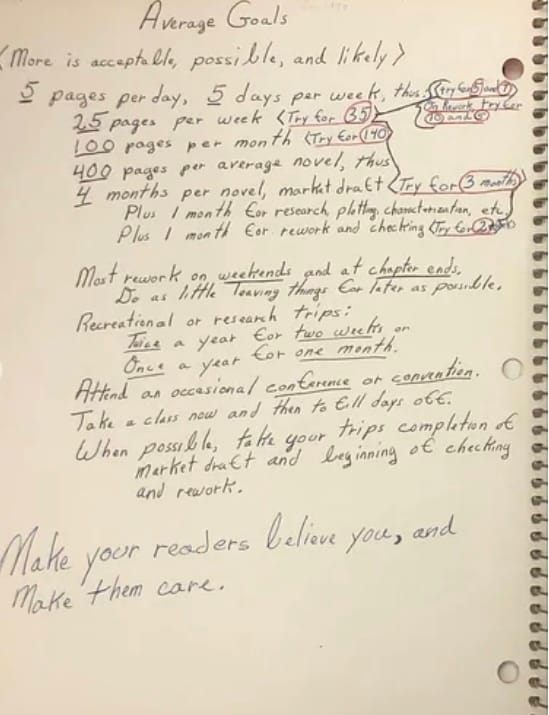

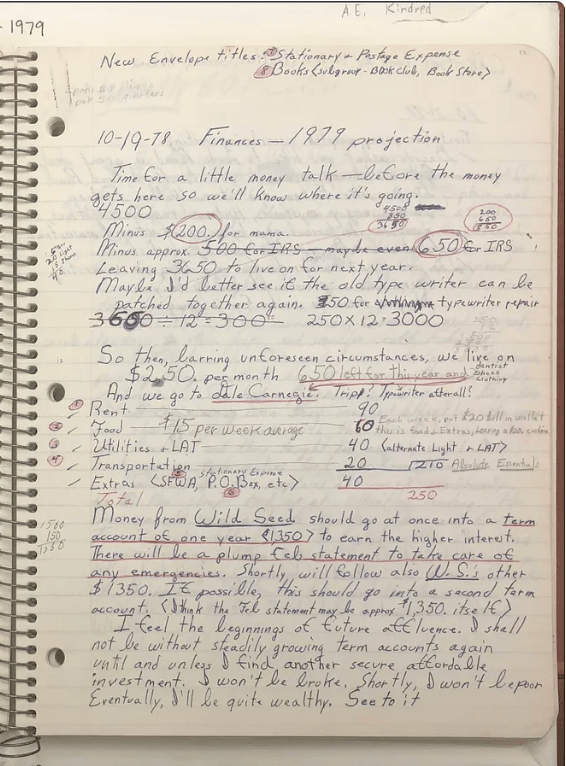

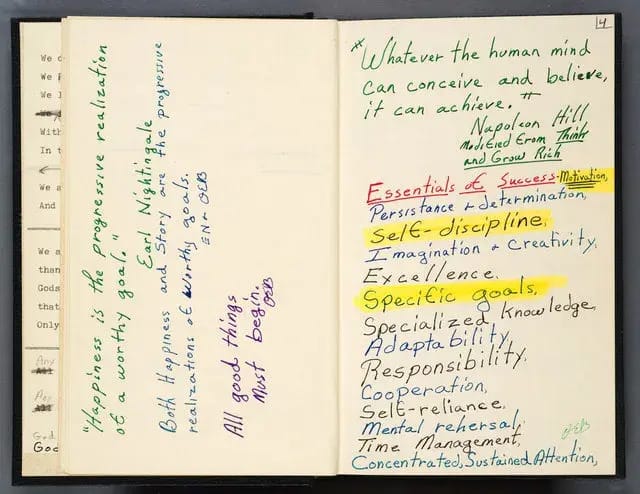

In high school, she'd enrolled in self-hypnosis classes and read Napoleon Hill's Think and Grow Rich. Hill's method was straightforward: write down your goal with specificity, rehearse it with conviction, treat the imagined future as present reality. Throughout 1970, Butler committed to this practice twice daily. Her journals overflow with declarations,"Goal: To own, free and clear, $100,000 in cash savings" alongside self-imposed contracts setting writing milestones: “5 pages per day. 5 days per week.”

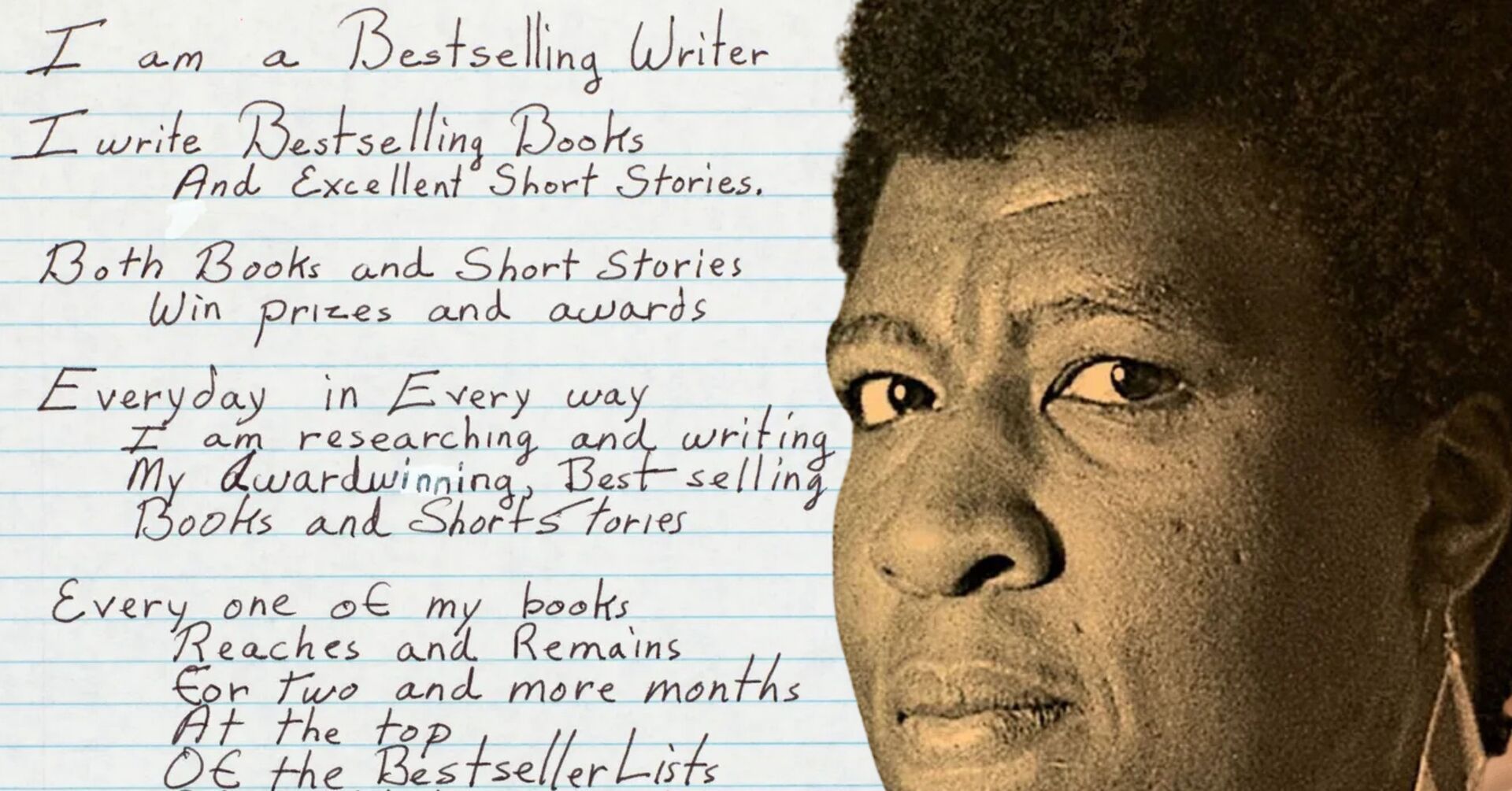

She began writing in careful handwriting, in present tense, as Hill specified in his book, as if it had already happened. As if this version of herself already existed.

She wrote these affirmations over and over, on scraps of paper, on the backs of notebooks, on the inside covers of her journals. She put them on her walls. She surrounded herself with this alternate version of reality, the one where she succeeded, where her books mattered, where she became the writer she could see so clearly in her mind.

She saw what didn't exist yet: Black women as subjects rather than objects of narrative. Slavery reimagined through speculative fiction in ways that revealed the true mechanics of power and survival.

You got to make your own worlds. You got to write yourself in. Whether you were a part of the greater society or not, you got to write yourself in.

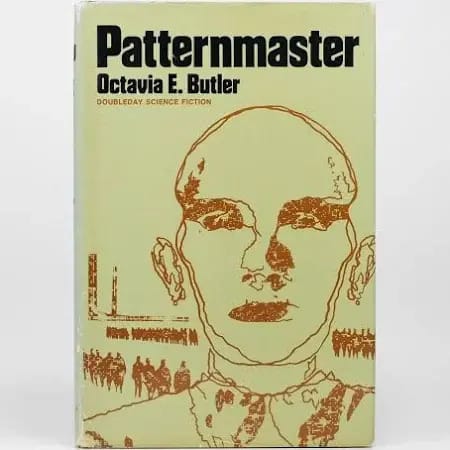

In 1976, she sold her first book, Patternmaster. The impossible thing had happened. And then, three years later, she sold Kindred in 1979.

In 1995, she won the MacArthur "Genius" Grant—the first science fiction writer ever to receive it. The $295,000 let her buy a house in a safe neighborhood, something her mother could never afford.

But she never became the bestseller she'd written herself into being. Not in her lifetime. The lists remained just out of reach.

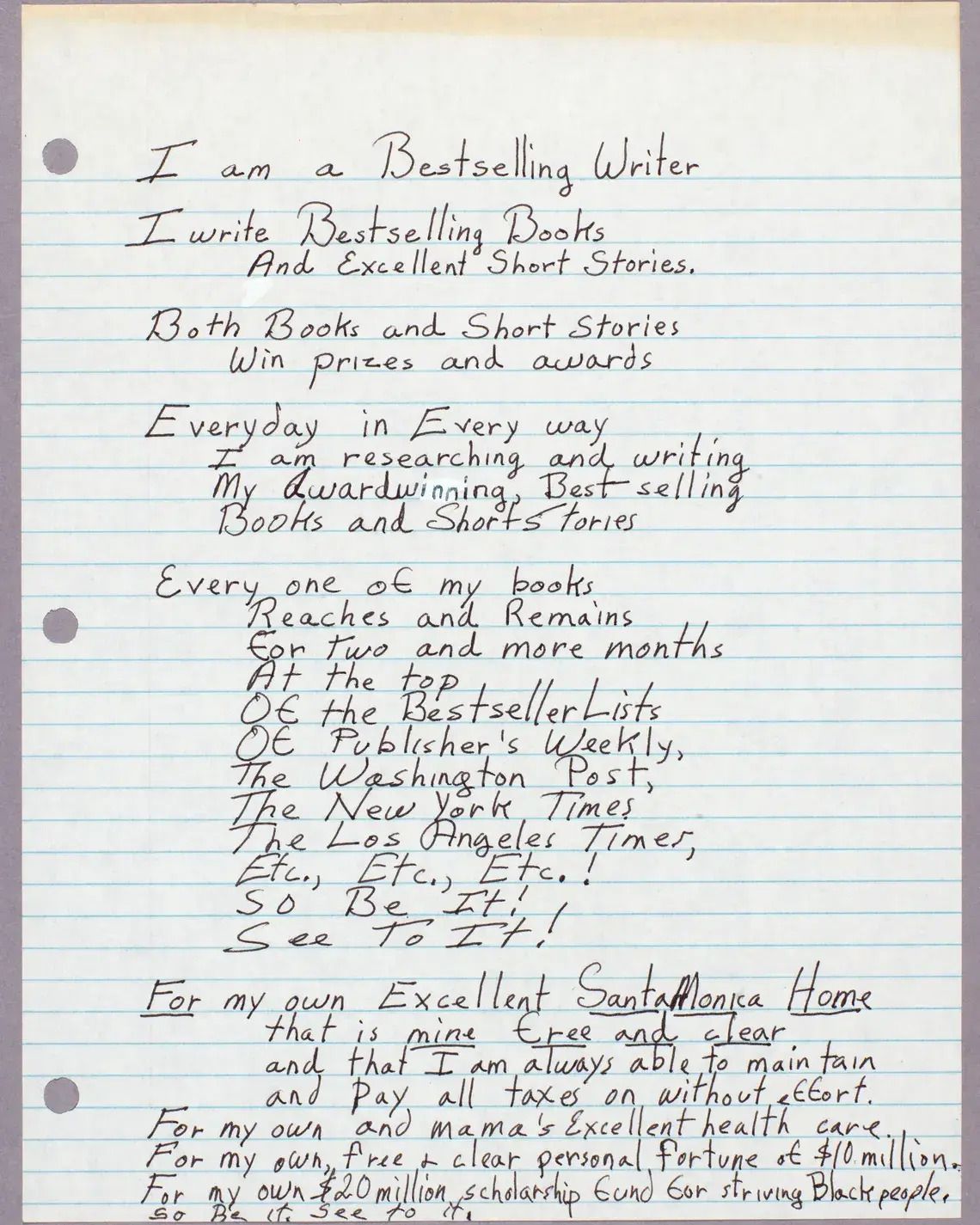

I shall be a bestselling writer. After Imago, each of my books will be on the bestseller lists of LAT, NYT, PW, WP, etc. My novels will go onto the above lists whether publishers push them hard or not, whether I’m paid a high advance or not, whether I ever win another award or not.

This is my life. I write bestselling novels. My novels go onto the bestseller lists on or shortly after publication. My novels each travel up to the top of the bestseller lists and they reach the top and they stay on top for months . Each of my novels does this.

So be it! I will find the way to do this. See to it! So be it! See to it!

My books will be read by millions of people!

I will buy a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood

I will send poor black youngsters to Clarion or other writer’s workshops

I will help poor black youngsters broaden their horizons

I will help poor black youngsters go to college

I will get the best of health care for my mother and myself

I will hire a car whenever I want or need to.

I will travel whenever and wherever in the world that I choose

My books will be read by millions of people!

So be it! See to it!

In February 2006, at fifty-eight, she was found outside her home after a fall. She'd been struggling with high blood pressure and heart trouble. Friends said she could barely walk a few steps without stopping to catch her breath. The fall may have been caused by a stroke. She died at the hospital. The future she had written in such careful handwriting stayed stubbornly in the future.

Except.

In September 2020, fourteen years after her death, Parable of the Sower hit the New York Times bestseller list. Her other books followed.

Her agent tweeted:

The future Butler had written in that 1988 notebook finally arrived—just not in time for her to see it.

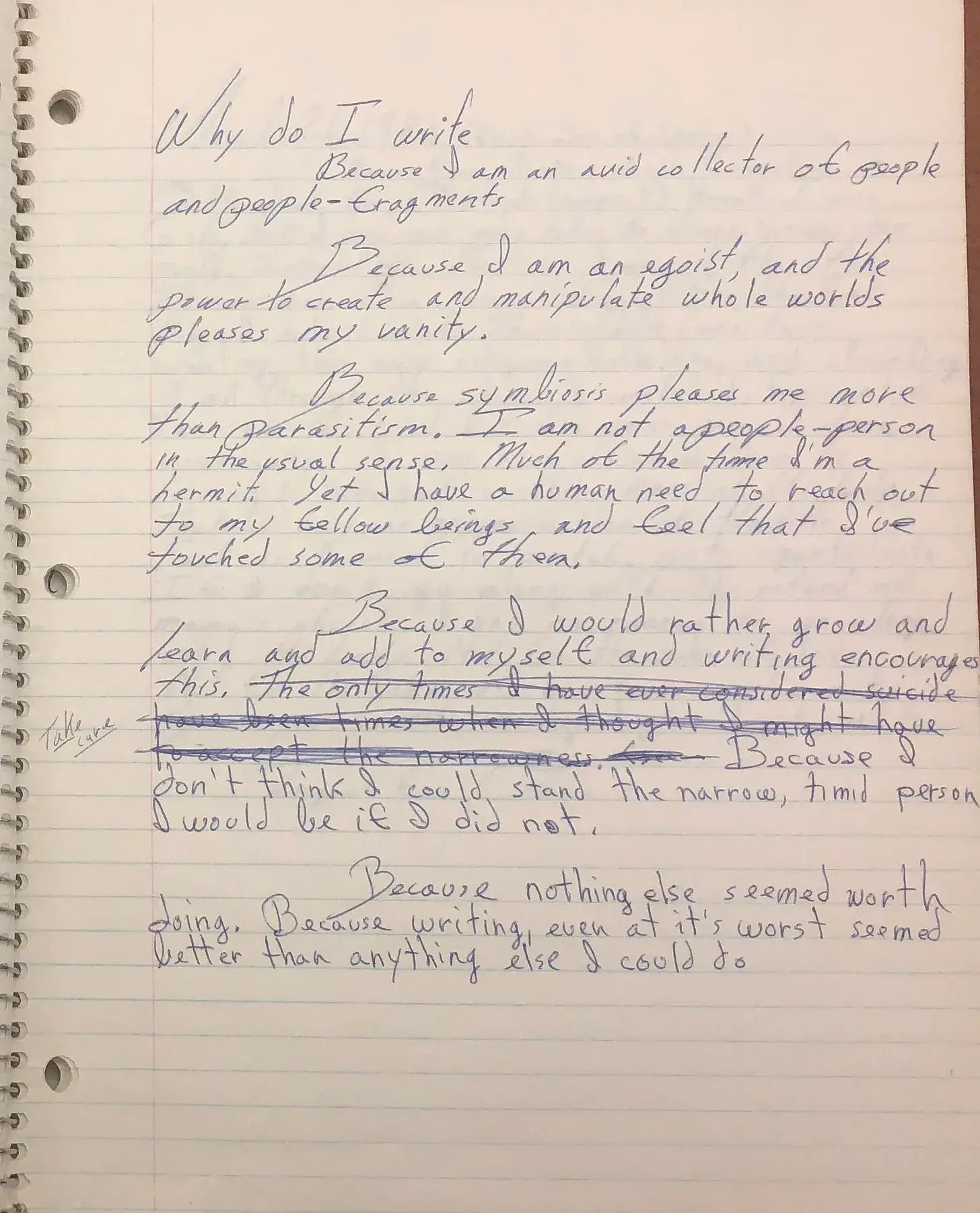

Butler didn't become a bestselling author whose books changed millions of lives. She already was that person. She was that person in 1970, inspecting potato chips at 2 a.m. She was that person through every rejection letter. She was that person when publishers didn't know what to do with her work. She was that person when she died without ever seeing her name on the bestseller list.

The affirmations didn't create a future self. They clarified a present truth that the world hadn't recognized yet. She wasn't manifesting. She was insisting on reality from a position the world couldn't see yet.

In an interview, Charlie Rose asked if she was surprised she became a writer. She said no. "I think I had two choices: I could become a writer, or I could die really young. Because there wasn't anything else that I wanted.…You got to make your own worlds. You got to write yourself in."

This is the thing about identity that we keep getting wrong: we think we become who we are through external validation.

We think the bestseller list makes you a bestselling author.

We think the MacArthur makes you a genius.

We think publication makes you a writer.

But Butler understood something we’re not taught. You are who you believe you are, right now, in this moment, regardless of what the world reflects back. She was a bestselling author whose work would be read by millions and taught in classrooms and change the shape of American literature—she was that person the whole time. The world just took decades to catch up to what she already knew.

The work of our lives isn’t becoming someone new, it’s recognizing who you already are. Not writing yourself into your imagined future but living from it now. Butler didn't wait for permission to be important. She didn't wait for the world to tell her she mattered. She decided she was a writer whose work would change people's lives, and she lived as that person every single day, even when every external circumstance suggested she was delusional.

She was right. The world was wrong. And eventually, the world figured it out.

What if you're already the person you're trying to become?

What if you've always been that person?

What if the only thing standing between you and that reality is your willingness to believe it before anyone else does?

That's what Butler's notebooks teach us. It takes real courage to believe in yourself despite what the world wants you to believe. You can be terrified—she was! You can be terrified, and do it anyway.

You are already the person you aim to be in the future.

Happy New Year, friends.

Amanda

P.S. Thank you for reading! This newsletter is my passion and livelihood; it thrives because of readers like you. If you've found solace, wisdom or insight here, please consider upgrading, and if you think a friend or family member could benefit, please feel free to share. Every bit helps, and I’m deeply grateful for your support. 💙

Quick note: Nope, I’m not a therapist—just someone who spent 25 years with undiagnosed panic disorder and 23 years in therapy. How to Live distills what I’ve learned through lived experience, therapy, and obsessive research—so you can skip the unnecessary suffering and better understand yourself.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Every bit goes straight back into supporting this newsletter. Thank you!

Upgrade

Upgrade