You are reading The How to Live Newsletter: Your weekly guide offering insights from psychology to help you navigate life’s challenges, one Wednesday at a time.

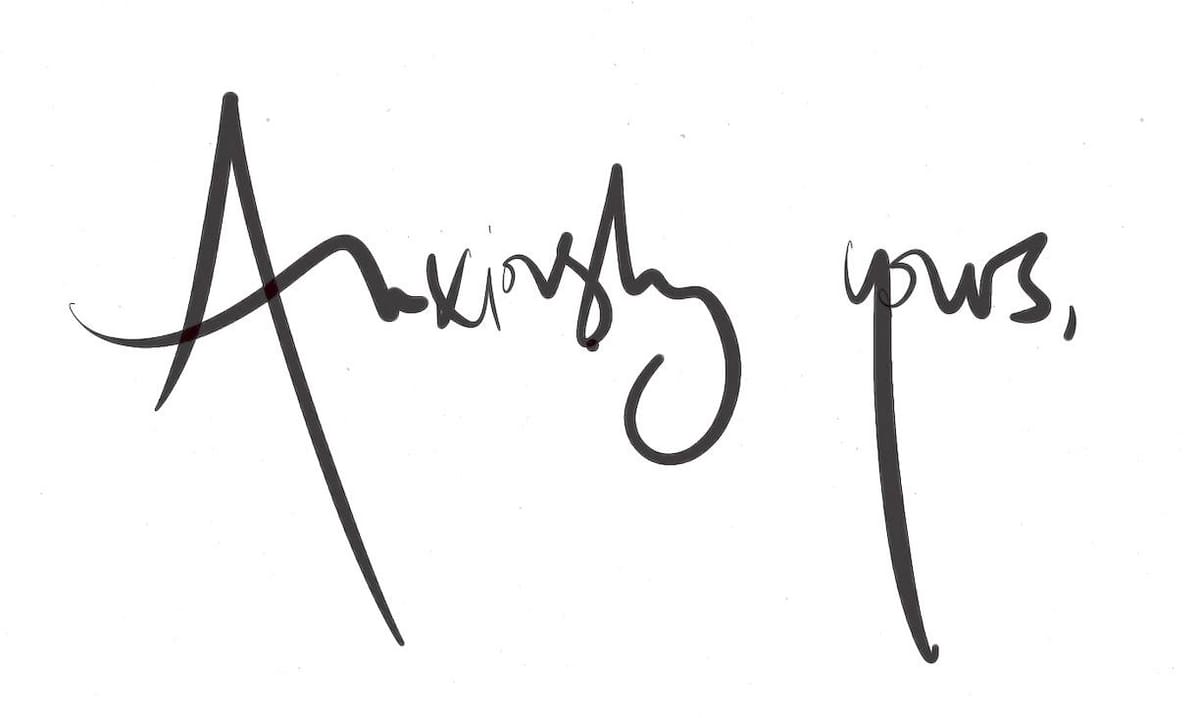

In 1902, Sigmund Freud sent this invitation to the Austrian psychotherapist Alfred Adler:

Upon his acceptance, Adler became a member of “The Wednesday Psychological Society” (later the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society), whose ideas would eventually become known as modern psychology.

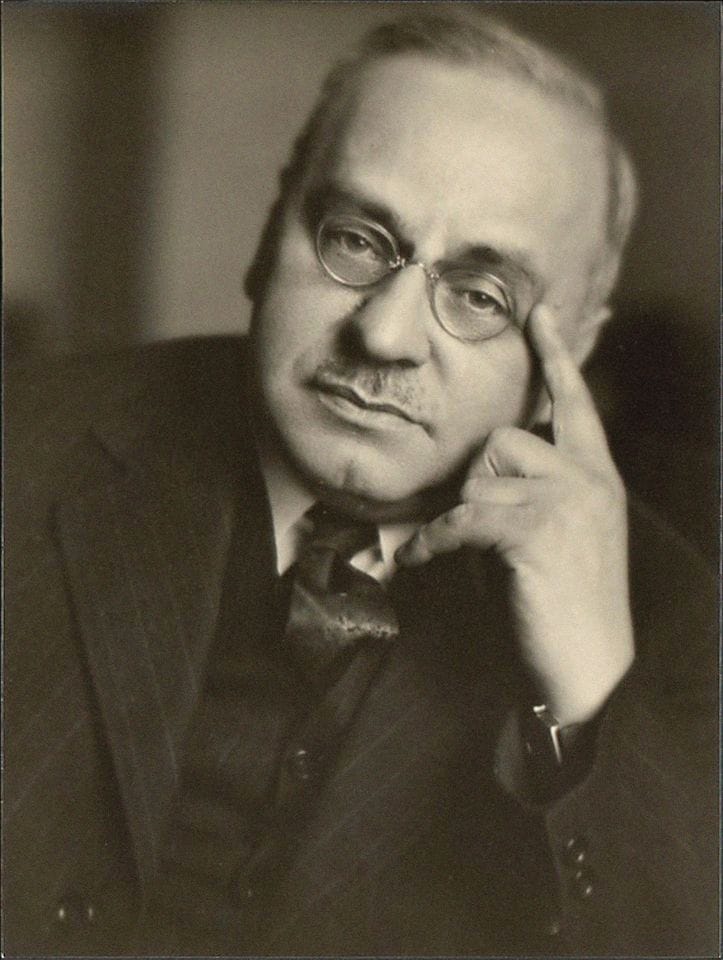

But in 1912, Alfred Adler broke away from Freud as it became clear their ideas were too divergent. The internal world captivated Freud, almost to the exclusion of external elements—he believed that people were ruled by the subconscious and put high stock in the concept of a split personality.

Adler, on the other hand, believed that everyone shared the need to belong and that personal problems were, in fact, interpersonal. According to Adler, Freud overemphasized sex to explain human behavior.

Instead of looking at a person in isolation to understand their behavior, Adler saw people through their family system, friendships, societal roles, and culture. To understand a human being involved, consider the internal and external worlds together.

Adlerian psychology is the psychology of growth, where people strive to overcome difficulties and actually change their lives. Though his name may not be as well known as Freud and Carl Jung, Adler’s original ideas are embedded in modern practice.

Alfred Adler | Getty Images | Heritage Images / Contributor

Consider the best-selling book, The Courage to Be Disliked: The Japanese Phenomenon That Shows You How to Change Your Life and Achieve Real Happiness (which has sold over 3.5 million copies–almost outselling my book Little Panic: Dispatches from an anxious life) written by two Japanese Adlerian practitioners Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga, who explain, through a dialectic (which takes some getting used to), how we can apply Adlerian Individual psychology to contemporary life.

The book's framework uses the Socratic method to explore Adler’s methods. In a wide-ranging conversation between a student and a philosopher, they discuss the concepts that makeup Individual Psychology, a social science that emphasizes self-reliance and living in harmony with society.

To attain these objectives, one must face what Adler called “life tasks.”

Adler held that everyone has three basic life tasks: work, friendship, and love (or intimacy). When these three areas bring meaning and fulfillment, you have realized your life tasks.

Original art for How to Live is by Edwina White

Every person, when living as a social being among others, must confront the task of interpersonal relationships. When one gets a job, they must cooperate alongside other people and work together to get good results.

But people, being people, often get confused by these life tasks. They get caught up in what others think of them, whether they are recognized how they wish.

They get caught up in other people’s tasks.

And because of this, Adler insisted that we always ask ourselves: “Whose task is this?” And if it’s not our task, we must separate it from others.

In other words, what someone else thinks of us is not our task.

If you live your life seeking forms of validation from others, then you are living according to other people’s expectations.

“Do not live to satisfy the expectations of others.”

We are beholden to their thoughts and judgments when we worry about what other people think of us. We are living to please others so that we will feel pleased with ourselves, but if we can only feel happy when someone else rewards or validates us, then we are swearing loyalty to someone else and living their life values, not ours.

It’s living a lie to outsource your sense of self and worth based on someone else’s viewpoint.

When you concern yourself with what others think of you, you live outside your life’s tasks and inside someone else’s.

Adler’s advice?

Have the courage to be disliked.

Adlerian psychology is for changing oneself, not for changing others. This boundary is important when you are caught up in whether or not another person likes you.

Always ask: “Whose task is this?”

Adler’s approach was person-centered and humanistic. To understand a person, you must understand that person in relation to others and social systems. All behavior occurs in a social context. After all, the foundation of our first few years is molded within the social context of a family—regardless of the configuration.

Those who study Individual psychology are interested in a growth model, meaning that one’s fate is never fixed or predetermined; individuals are always in the process of “becoming.”

What distinguished Adler’s school of thought from his peers in psychoanalysis was that his focus on individuality included the entire person, their family, school, and social ties. Community and the context in which a person was raised are essential to shaping an individual. He believed a person’s problems couldn’t truly be understood without understanding these elements.

If a person was shown where their approach to life (which he called their “lifestyle” or “style of life”) was impeding their growth, they could begin to understand how to live according to their values.

Babies, Adler believed, all suffer from an inferiority complex because they are born helpless. Some babies feel so incomplete and helpless that, as they grow, their uncomfortable emotional state begins to inform their choices and behavior. This is called overcompensating.

This behavior hardens into a model upon which the baby develops, moving from one state of growth to another, where the person constantly seeks ways to feel increasingly superior. This compensatory behavior can cement into a lifestyle that lasts a lifetime and is always made worse when in a relationship with other people.

Adler was interested in the role of inferiority in personality development and believed that people could change their concept of self.

Because of our innate sense of inferiority, Adler saw that many people get caught up in living their lives according to external measurements and markers. They live according to perceived expectations explicitly stated by parents or family or from cultural osmosis.

However, our dependence on others’ perceptions of us is not entirely in vain. It is part of our evolution. We were once a part of small communities and tribes. Instead of riding alone, existing within a community made us safer from predators. But that comes with its own dangers.

Because being cast out could mean death. So, this fear of being castigated or exiled is evolutionary. Instead of prehistoric predators, we are swallowed, invalidated, and erased by our peers and authority figures. We don’t want to be punished; we want to be recognized and rewarded.

The trouble occurs when our fear of being disliked or rejected overtakes our choices.

Adler believed that life is created by the meaning we give to experience. It's not the trauma that makes us suffer. It’s our reaction to trauma that makes us suffer.

Being the person we want to be takes courage, and searching for our authentic selves is an ongoing project. We must rid ourselves of past experiences and expectations to strive toward self-actualization. We must embrace the courage to change without feeling limited or scared of what could happen.

We tend to believe that our identities are fixed and that we're trapped inside the person we are. However, we have the power to change no matter what stage in life we're at; we can always shift and grow—but it’s practically nonsensical to embark on such an odyssey when you are preoccupied with the fear of being disliked.

This is just skimming the surface of Adlerian psychology. To dig deeper, I recommend reading The Courage to Be Disliked and/or this chapter on Adlerian Theory.

And you?

Do you fear being disliked? Have you ever experienced a momentary reprieve where you simply didn't care? Let me know in the comments.

Until next week, I remain…

Amanda

If anything you've read resonates or rings true, please consider a small or large donation to keep this paywall-free and accessible to everyone.

VITAL INFO:

Nope, I am not a licensed therapist or medical professional. I am simply a person who struggled with undiagnosed mental health issues for over two decades and spent 23 years in therapy learning how to live. Now, I'm sharing the best of what I learned to spare others from needless suffering.

Most, but not all, links are affiliate, which means I receive a small percentage of the price at no cost to you, which goes straight back into the newsletter.

💋 Don't keep How to Live a secret: Share with friends

❤️ New here? Subscribe!

🙋🏻♀️ Email me with questions, comments, or topic ideas! [email protected]

🥲 Not in love? Unsubscribe!