BOOKS

There's a new place for book discovery in internet town! It's called Shepherd. Writers make booklist recommendations for them. They asked me to create one, and I did. Follow the link below to find...

CHRONIC ILLNESS.

The Invisible Kingdom came out in March 2022 and became an instant New York Times Bestseller.

The book, written by journalist, editor, and poet Meghan O' Rourke, blends the personal and the universal, bringing us an essential and revelatory investigation into invisible illness and how inherited ideas about the cause, diagnosis, and treatment have blinded us to hard-to-understand conditions.

Meghan and I spoke 5 months ago about her book, and our experiences trying to get medical help and treatment.

Today's piece offers you a transcribed section of that talk (edited for clarity and brevity). The full video conversation is included below. I could not get the video to load, so there is a link to the actual video under the screenshot...

Amanda Stern (AS)

Okay, we are live. Hello, Megan O'Rourke, I am so happy that you're here.

Meghan O’ Rourke (MOR)

Hi, Amanda. This is just such a pleasure and a dream to be able to speak with you today. So thank you. And thanks to anyone who's watching.

AS

You're very welcome. I want to get into the book, but what makes this so pleasurable and amazing for me besides like, knowing you and thinking the world of you, is that I remember when you were writing this book and running into you on the street during the process of it, and you were like, I'm never going to be able to do this.

MOR

Yeah, absolutely.

AS

But you did it.

MOR:

Laughs.

AS:

Not only did you do it but, for those who are just tuning in, you found out yesterday, that it’s number six on the New York Times bestseller list. I'm just so endlessly pleased for you, because I know what a struggle this was.

MOR

It was a labor of love.

AS

It was, and I’m so amazed that you wrote this when you were not well. Do you want to talk about the origin story of your illness, which is hard to pinpoint, but the general curve of it?

MOR

Yeah. So, in my book The Invisible Kingdom, reimagining chronic illness. The way the book begins is by saying that illness narratives usually have a startling beginning, a sudden call from the doctor for a test result that brings bad news, but mine was like wading into water slowly, getting deeper and deeper without knowing how to swim.

Which is to say I didn't exactly know I was sick for a long time, having a variety of seemingly small problems that would come and go, and I was going to doctors and saying, I have hives every night, what's going on?

And they would test me for lupus, and there would be a suggestive test, and they would say, “Maybe you have Lupus,” and then the next test would look fine.

And it would go back to “Maybe you're a little stressed, and that's all and just take some antihistamines,” right? So, versions of this with different symptoms went on for more than a decade, until my mother died, at which point I was suffering—I should give you a sense of what the symptoms were—the most significant were these bouts of fatigue (which is really the wrong word).

I want the English language to come up with another word; it was more like cellular enervation and my body was just grinding to a halt.

Brain fog—again, slippery concepts, but quite profound to experience. In my case, it was really difficult to write and put sentences together. One day, I was trying to explain to my students that this was a poem about spring and I could not, for the life of me, think of the word spring. I mean, that wasn't the only word, there were a whole host, I would have to say things like “the season that comes after winter.”

So if you knew me at this time, I might have seemed fine, but if you really listened to my language, you would have heard that I was struggling to articulate myself.

It is a truth universally acknowledged among the chronically ill that if you are a woman in possession of a vague set of symptoms—to paraphrase Jane Austen—you are in search of a doctor who believes you.

Getty Images | David Wall

After my mother died, I was 32—this is about 10 years into these symptoms—I got a virus and I just never got better, and I ended up being pretty much bedridden, which sent me on a more concerted quest to get recognition because at that point, I realized it couldn't keep taking “Maybe you're just stressed” for an answer.

Over time I was diagnosed with an autoimmune thyroid condition with a vague autoimmune disease that no one quite knows what it is: it’s Lupus-like, and then with Lyme disease. I also have something called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and POTS which some of your listeners may know about.

AS

So, during that experience, I imagine it must have been really difficult to get any doctor to take you seriously. Going in with vague symptoms is a really difficult experience. Can you talk a little bit about what you came up against?

MOR

It is a truth universally acknowledged among the chronically ill that if you are a woman in possession of a vague set of symptoms—to paraphrase Jane Austen—you are in search of a doctor who believes you. I had great doctors, and many of them didn't actively dispute me, but they didn't really believe what I was saying.

They weren’t moved enough to say “God, I’ve got to help this person figure out what's wrong” and what I realized was, I was hardly alone, that there were just tons of people going through this.

And research shows that to be true. And my own interviews with patients, I talked to almost 100 mostly women, and you know, this applies, by the way, pretty much to everybody. Men experienced this too. And I think non-binary people experience especially.

But women get a particular flavor of it, which is really bound up, I think, with the history of hysteria. And this reflexive assumption that when women are speaking about vague bodily problems that don't show up on lab tests, they are really, in essence, repressed psychological issues, right?

Then there's this additional problem, which is that medicine just hasn't researched women's bodies very deeply. So, this kind of reflexive cultural habit of distrusting women's testimony is particularly pernicious because it meets or butts up against an actual lack of scientific knowledge.

What is clear is that medicine has mostly researched biologically male animals and humans, which is astonishing to discover—a really good book by Maya Dusenberry that I recommend to people who are interested in this subject where she just reports out very powerfully, how problematic the knowledge gap is.

AS

Do you remember what it's called that?

MOR

I think it's called Doing Harm. But this is where my brain fog still exists. Yes, it is. I got it, right. It's called Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed and Sick and I read it after I'd finished writing my chapter on women and then I wanted to quote her because her work is so good.

AS

I was doing research on John Sarno—I know people have brought him up to you—and I came across a fact that alarmed me, which was that you don't learn psychiatry or psychology in medical school. You might take one class. There seems to be such a lack of knowledge about how the [mind-body] systems work together. Not being heard, not being seen, activates a stress response that makes you sicker.

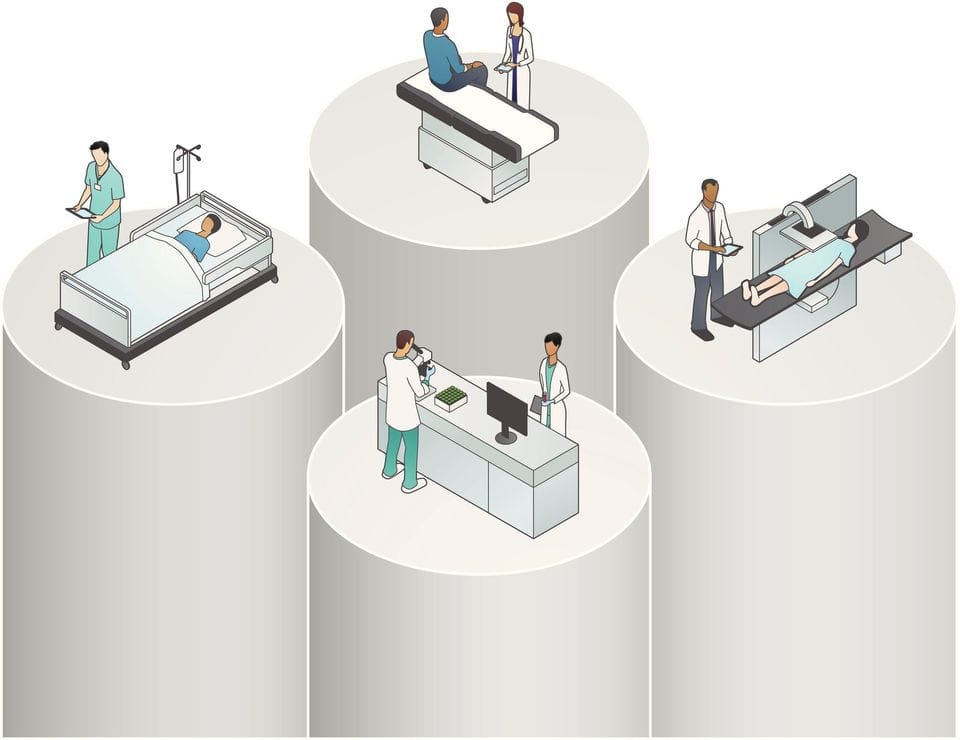

It's so non-integrated. And I’m curious about the silo-ization of our healthcare system, and why that is. It just makes no common sense to me.

MOR

Yeah, I 1,000% agree with you. We could just talk about this for the rest of the time. One of the things I point out in my book is that often people with vague subjective symptoms, we've talked about this, are reflexively told, or it's suggested to them pretty much immediately, that those symptoms are psychological in nature.

It often creates a barrier to further inquiry that might uncover organic problems, like physical problems elsewhere in the body. The problem as you say is that these systems are actually powerfully intertwined, right? Sometimes medicine operates a little bit as if we're Descartes. There's a mind and a body, and they're totally distinct.

We know that science itself is telling us that the brain and other organs and our immune system are deeply, deeply interconnected.

Getty Images | mathisworks

And I tiptoe into this research in my book. There’s an entire emerging field of what's called psychoneuroimmunology, which shows that the ways in which, as you say, stress can actually worsen the realities of our immune system: It can make you sicker.

By the same token, one of the things I saw a lot was that—and I just was reading an article from someone at Harvard about this last night—he says we know that a lot of people with depression have these physical symptoms and aches and pains. So therefore, long COVID probably is partly caused by anxiety that people have in a pandemic, which to me is, you know, a number of leaps that doesn’t make sense.

For one thing, what I found was that doctors, if you went into the doctor's office saying you have any anxiety, that became the final answer, right? And a lot of people I reported on told me that they did have anxiety, they also had all these physical symptoms. And what I found astonishing was that doctors were not like, “This is so fascinating. I wonder if there's a connection between this anxiety and these other inflammatory symptoms they have”?

There's something called Neuro-inflammation, there's something called the blood brain barrier, people used to think lots of viruses and things didn't get into our brain and we now know that pathogens can get into our brain, and we've seen evidence of COVID there.

And the brain can experience inflammation in ways that the body can. So, these are part of a system that need to be, as you're saying, treated as a system and not looked at as an either or, but maybe as a “both and.” And right, yes, this person has anxiety, what else might be there?

And in fact, rather than her physical symptoms being psychosomatic, might the anxiety be soma-psychiatric which is driven by problems in the immune system. These are things we don't understand very well.

AS

It also just seems to me that there's a level of incuriosity that I've never understood, and I have this real desire to be existing in the time when we can go to the doctor and say, Here, here's what it feels like, and just put it in their body. If the doctor has not experienced what you've experienced, it doesn't exist, they don't believe it.

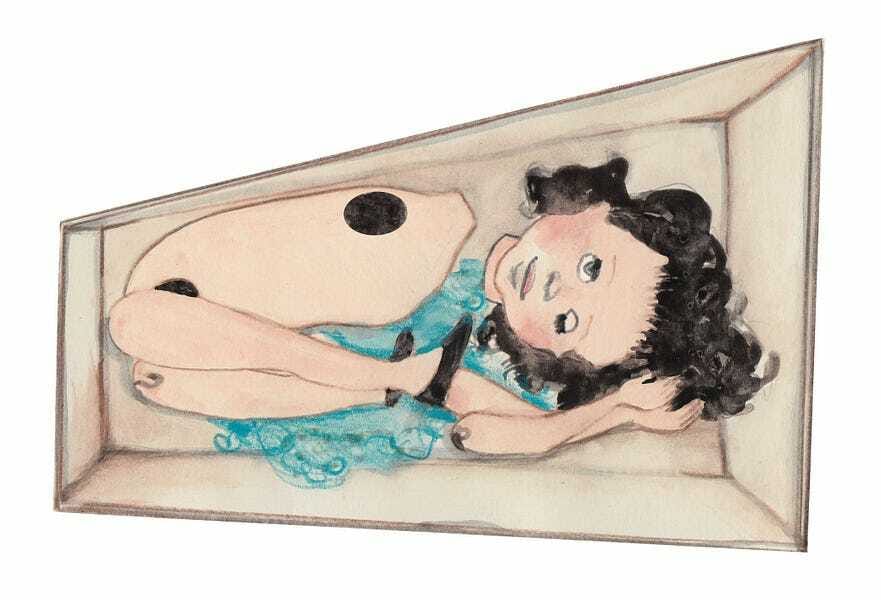

Original art by Edwina White

MOR

They don't necessarily have to have experienced it, but they need to have a measurement of it.

AS

Right, exactly. And I get that, but I also just don't understand how if you're a doctor, and you're treating a human being, how you will be so incurious about all the aspects that make a human being who they are.

If you can't measure it, it doesn't exist, and that makes living with invisible disorders so complicated and confusing, and it finds them stigmatizing the things that you need help with. Can you talk a little bit about the other symptom? You had electrical zaps.

MOR

Yes. I had a lot of neurological symptoms, almost primarily neurological symptoms in addition to the fatigue. I had these strange electric shocks, I still get them to this day, a little bit less than I used to, but they are like someone's zapping me with conductor all over my body, particularly my arms and legs.

It's a really maddening thing, really challenging sensation; it may be connected to something called Small Fiber Neuropathy, but mine doesn't quite operate like that.

Anyway, this was by far one of the most challenging symptoms I lived with. But when I went to a rheumatologist, for example, for my autoimmune disease, because that's not the world of the rheumatologist, they were mostly incurious; they wanted to hear about joint pain, if I had rashes, or if these things that slotted into kind of a pre-existing module for what might help them diagnose me with autoimmune disease.

So, one of the things I really talk about in the book is modern medicine relies on measurement and it relies on sort of replicable and tidy categories of disease. But the challenge for those of us living with invisible illnesses is that we're at the edge of medical knowledge. We lack the diagnostic tools and good treatments, and so you go in, and there might not be a test yet for exactly what's wrong with you.

Autoimmune disease research is about 10 years, if not more, behind cancer research. And a lot of tests only work when you're already pretty sick. So, the astonishing thing is that medical doctors should know that, right? They should know that and think, when you have a patient like me, maybe I should take their family history and find out if there's autoimmune disease, if there's a genetic component.

So instead, though, if you're at the edge of medical knowledge, you become suspect, right? Rather than medicine reaching out to say, “Wow, you might be one of these people we don't know how to help yet.” So that, to me, was one of the great frustrations and mysteries.

And as you say, this lack of curiosity. I would tell my husband often after a doctor appointment, aren't they interested? Like, it’s weird, right? It's a weird story.

But the reality is that I think in our very siloed and compartmentalized system, where American doctors, in particular, are under an extraordinary burden of paperwork, bureaucracy, pressures from insurance; they can't afford to take up that interest.

They don't have the time in their day. And I actually feel empathetic to doctors too, even as I'm frustrated with the system which is failing them and us.

FOR THE REST OF THE CONVERSATION, GO HERE...

Have you struggled with invisible illness, or struggled getting a doctor to believe in you, stand by your side and try and puzzle things out? Let me know in the comments!

Until next week I remain…

Amanda

(Nope, I'm not a therapist or medical professional. I'm just a human being who has spent most of her life trying to figure out how to live.)

Anything bought in the How to Live Bookshop can earn me a small commission, which goes to subsidize this newsletter.

📬 Email me at: [email protected]

📖 Buy my book Little Panic: Dispatches from an Anxious Life